It’s a testament to technological progress that lighthouses have become scenic. These towers with their glass rotundas are now mostly quaint relics whose images evoke nostalgia and attract tourists to coastal towns. But most of these pillars of civilization were built not to soothe or attract but to warn and repel. They identified hard-to-see shorelines and hidden reefs so that sailors could avoid damage, loss of cargo, and loss of life. As Tom Nancollas writes in his book Seashaken Houses: A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet, “There can be few other buildings designed expressly to repel, to emphatically not be seen at close quarters.” It’s splendid that a giant WARNING symbol is now a greeting card image.

I spend most of my waking hours trying to help people see and comprehend new risks that they now face and ones that they, their descendants, and all of the people and other living things will encounter as the atmosphere warms. Probable Futures, the nonprofit initiative that I help lead, is a modern, digital version of a lighthouse. I have come to appreciate lighthouse builders and keepers. They were unusual people whose work had huge implications that could never be observed. Constantly helping people see risks can feel odd and isolating. While others struck out on adventures that might have resulted in carefully counted riches and exciting tales, the successes of lighthouse builders and keepers were wrecks that didn’t happen, lives that weren’t lost, and cargo that didn’t sink to the bottom of the sea.

Most lighthouses were built in an era when seafaring was the most viable path to fortune for people in Europe and North America. Innovations that could lower the risks of adventure therefore offered huge potential payoffs for society. Over time, nautical maps got better, and sensors and other technology allowed sailors to know their location even in storms. The seas became known and reasonably safe. It wasn’t just the seas. Life got less risky for most people on the planet as time went by. Eventually, communities stopped lighting their lighthouses.

We are leaving the age of low, stable, and well-known risks and entering one of rising temperatures, oceans, and levels of distracting information. Navigating climate change and whatever digital future we are racing toward will be much less dangerous if we build and maintain new, reliable beacons to steer us away from hazards, to warn us of the new perils people will meet at sea, on land, and in the virtual world, and to help us navigate to better destinations.

Traditional lighthouses were built to guide people who had chosen to brave the seas. We now need infrastructure that functions like lighthouses, not just for the venturesome but even—perhaps especially—for people who think they are safe at home.

Woeful landmarks

Off the coast of Rockport, Massachusetts, stand two stereotypical lighthouses on a small island. I first saw them while lounging on nearby Good Harbor Beach, well before I had begun learning climate science. I appreciated them as quaint, decorative baubles on New England’s charmingly rocky shore. In recent years, however, as I sat on the beach, I began wondering, “How many boats wrecked there and how many people died before people decided to build a lighthouse?” “How many meetings took place before a group sponsored the building and designed it?” “Who paid to build it?” “Why are there two lighthouses on one island?” “What did it feel like to live in a building whose main purpose is to loudly shout ‘Stay away from here!’?” and “Would that lighthouse get built today?” The answers turned out to be not only interesting but insightful.

In 1635, the people of Marblehead, Massachusetts, persuaded a minister named Joseph Avery to move to their town to be their pastor. Avery was reluctant because most of the community were sailors, a group he considered to be “loose and remiss in their behavior,” but the terms were favorable enough for Avery, his cousin Anthony Thacher, and their large families to leave their homes further north in the colony. In August of that year, the entire party of 23 boarded a small boat curiously named the Watch and Wait to sail to their new home. A couple of days into the trip, as the boat was rounding Cape Ann, the weather got rough, so the captain and crew anchored the boat to watch and wait for calmer seas. Instead of friendly breezes, however, they got a hurricane, which dragged the boat and its anchor and eventually hurled the craft onto a jagged reef. The entire crew, every member of the Avery family, and all of the Thacher children perished.

Thacher and his wife survived. They washed up on a small uninhabited island a half mile from the reef and a mile from the mainland. Five days later they were able to hail a passing boat. A month later, the legislature granted Anthony Thacher 26 pounds (about one year’s wages for a professional) for his losses. A year later the colony awarded ownership of the island to Thacher as “his proper inheritance.” Thacher, who named the island Thacher’s Woe, moved first to Marblehead and then down to Cape Cod, where he was one of the founders of the town of Yarmouth. He later sold his woeful island.

In the following 146 years, many ships wrecked on the same reef. As the colony grew more prosperous and shipping became more profitable, merchants and shipowners repeatedly petitioned the government to build a lighthouse nearby to warn sailors. Otherwise, they feared, not only would shippers and merchants lose ships, goods, and lives, but business would shift to other ports. They understood that the best strategy for coping with a risk was helping people see it.

In 1771, the legislature appointed John Hancock, a Boston merchant and shipowner, to be the head of a new committee to draft a lighthouse bill for Massachusetts. The government purchased Thacher’s Island (locals had stopped using the “Woe” part of the name) for 500 pounds and decided to build two lighthouses set about 900 feet apart. While two lighthouses were more expensive than one, the committee believed the extra investment was worth it because sailors who saw only one light might mistake it for the single lighthouse in Boston Harbor that was designed not to repel sailors but to attract them. As Eric Jay Dolin writes in Brilliant Beacons: A History of American Lighthouses, “Whereas all previous colonial lighthouses were intended to guide ships safely into and out of port, Cape Ann’s twin lights were the first to warn of a specific danger. The residents of Cape Ann, enamored and thankful for the twin lights, soon began calling them ‘Ann’s Eyes.’”

Yet just a few years later, on orders from the same legislature, Captain Sam Rogers, a doctor in nearby Gloucester, led a rebel militia out to Thacher Island to smash the lamps and all of the glass in the lantern room, remove the whale oil used to light the lamp, and evict the lighthouse keeper and his family from the island. As Dolin writes: “Lighthouses do not distinguish between friend and foe,” and the rebels now had foes. A cheap way to interfere with the British ships that supplied British troops was to extinguish the lights. The twin lighthouses were only repaired and relit after John Hancock put his fancy signature on the Declaration of Independence.

A serious metaphor

I have come to believe that lighthouses are excellent symbols of the best aspects of civilization, the millennia-long process of settlement, urbanization, specialization, governance, trade, and overall complexity. When it works well, civilization enables people to plan, work together, learn from each other, make long-term investments, worry less about risks, and undertake adventures.

The wealthy people who advocated for and found ways to fund illuminated stone towers wanted their societies to thrive and worried that hard-to-see perils might undermine their communities’ chances at prosperity. These were people who understood uncertainty and risk. As Nancollas writes in Seashaken Houses, “Then, the sea was an unknown realm that could lead to new territories with resources to capture and exploit.” His book focuses on the remarkable structures that sit entirely on barely visible rocks and reefs off the coast of the British Isles:

It is not easy to establish an enduring presence in an unstable medium like the ocean. Firm structures are seemingly incompatible with this fluid setting. All too frequently, man-made things lose their buoyancy and plummet to the sea floor. Flotsam is ushered toward land and ground to pieces in coves until nothing is left, as though the sea is in a never-ending cycle of erasure.

…

One by one, those dangerous reefs were neutered. As well as seafarers’ lives, national prosperity hinged on safe passage through shipping lanes, estuaries, and ports. This was a forward-looking age, an age of improvement.

I’ve now read quite a bit about lighthouse history, politics, and economics. None of the documents suggest that anyone at the many meetings that preceded construction of any lighthouse voiced the concern that the sea level might rise or fall, making the old hazards less risky or creating new ones. They debated costs and benefits, materials and governance, architectural style and fuel source, and forecasts of shipping business, but everyone involved assumed that the ocean would stay at exactly the same depth in perpetuity. And indeed, the big, sloshy, unruly seas fulfilled their expectations for centuries. Now, however, the reef off Thacher Island is growing less threatening to boats as the local sea level rises, the probability of hurricanes at high latitudes is increasing, and at high tide the beachgoers at Good Harbor are crowded together, pushed back to the dunes by the rising sea. Perhaps more alarmingly, locations well inland, far from the threat of waves, are facing new risks.

Unfortunately, today’s business leaders aren’t lobbying for the government to illuminate risks and aren’t building lighthouses themselves. Instead, most of those who appreciate the new risks are either trying to benefit privately from their ability to recognize dangers or are trying to keep risks hidden. It turns out that societies led by adventurers who tend to be “loose and remiss in their behavior,” as Joseph Avery put it, are more likely to wind up in dangerous waters.

Smooth sailing

“What’s over there?” might be the oldest question humans have posed. From a biological perspective, adventure has offered potentially great evolutionary rewards. Men who tell stories of daring, conquest, and insight earned in faraway settings have long had an advantage in attracting a mate, likely because such experience (and surviving it) signals heartiness and courage. For a clan or entire species there are also great potential benefits of having adventurous members find new sources of food, discover new, hospitable lands to occupy, and learn superior strategies and techniques from other cultures.

Between about 9,500 BCE and 2015, most of Earth’s exposed land offered a temperate climate, and the seas and atmosphere rarely conspired to create storms that endangered people on land. Glaciers concealed the ground only in places that were no fun anyhow given their very thin air or long, dark winters, and nowhere on earth was too hot for the human body. In other words, almost every “over there” was worth checking out.

Even when adventurers wound up somewhere they didn’t intend to go, it was often rewarding. Over time, our species not only explored but occupied the vast majority of land on Earth. Humans were the biggest beneficiaries of this specific climate, but stability gave every species time to find fertile niches, specialize, and create complex ecosystems. For example, over thousands of years, monarch butterflies branched into three species and six subspecies, each of which had its particular locations to eat, breed, and winter, often with long migratory paths in between. Adventuresome (or simply lost) monarchs discovered suitable habitats in places as far apart as Hawaii, Australia, and Venezuela. The Northeastern Monarch figured out how to migrate between Maine and Mexico, Minnesota and Florida. When the world is safe and every landing place offers a potential bounty, the odds favor the daring, even the reckless.

There is good evidence that “uncivilized” species (i.e., every species except humans) remain keenly attuned to changes in the environment and risks that threaten their survival. In 2004, an earthquake rumbled deep in the ocean near Indonesia. Elephants, birds, cats, goats, and other animals began retreating from the coast, racing to higher ground. Some people followed the animals’ signals, but most saw no relevant information in the animal behavior, and 230,000 people lost their lives in the tsunami that followed.

Less dramatically, species including bacteria, birds, bees, butterflies, and beasts of all kinds are trying to figure out how to adjust to a changing climate. New England’s iconic lobsters, who thrived in the rocks off the coast, have been scrambling further north and into deeper waters as the ocean warms. The industry is basically gone in Rhode Island partly because the warmer waters are attractive to black bass who find baby lobsters delicious. Lobsters may be able to find the ocean water with temperatures to which they are adapted, but they face new perils. Will their food supply (much of which is migratory) move with them? Will the increasingly acidic ocean weaken their shells and upset their sense of smell, making them more vulnerable to predators? No one knows, but the lobsters are clearly trying to figure it out. We should be at least as good at this as lobsters are since we know what’s coming and can share stories with one another.

Unstable ground

Over the past several years, my colleagues and I have been invited to teach in several different executive education programs, graduate programs at multiple universities, and in convenings organized by individual companies or by industry groups and professional organizations. In these sessions we share climate information, data, and frameworks for assessing and addressing risks, offering examples of current and prospective problems around the world. And then we often ask people to share their own experiences. A few years ago, people were generally reluctant to speak up, unsure that it was socially acceptable or professionally advisable to talk about these things. But by 2025, almost everyone has a story. These stories aren’t mine to tell, but I can generalize and anonymize them to give you a sense.

A naval officer explained that because there is no infrastructure for dealing with climate disasters in his country, “The navy is being asked to fight wildfires, fill sandbags, and clean up after storms on land instead of monitoring and preparing for the rising military risks at sea.”

An executive at a manufacturing firm said, “We are selling all of our properties in Vietnam. In 20 years they won’t be viable because of sea level rise, so we’re getting out while there are still buyers.”

An executive from a marine construction company explained that port construction always involves downtime due to inclement weather or difficult conditions. They used to expect to be able to work three days out of every four. Now it’s more like two.

The managing editor of a global news service explained that they had a long-standing safety training practice to prepare journalists to work in conflict zones. They have had to reshape their program to train journalists—in every geography—to cover extreme weather events without getting hurt or killed.

An executive at a Chinese electric car company explained that flash flooding was an ever-increasing problem. So the company created a flood monitoring system that shows drivers of their cars how to avoid flooded roads, drive to higher ground, and even find safe parking garages. The customers love it, and the firm avoids expensive warranty claims.

The executives in these classes leave with more confidence to talk about climate risk within their organizations. They also understand better that these are just the early signs of risk, those that have emerged on the way to 1.5°C of warming, and that much larger risks are coming. For this, they have Probable Futures maps to help them navigate the future. I tell all of them that if they tell these stories to their colleagues, their customers, their suppliers, their friends, and the government leaders they interact with, they will be like lighthouse builders sending out helpful beacons.

Perversely, most leaders are incentivized to do the opposite, hiding their beacons and even extinguishing signs of impending risk.

Mooncussers and altruistic towers

When we were first building Probable Futures as a public gift, I was invited to meetings by consulting companies, banks, and regulators who were curious how the “climate risk space” might develop. These convenings would often also include entrepreneurs who were raising money to sell similar data under the umbrella of “climate analytics.” Their pitch was that the climate was getting more risky, so smart companies should hire them to illuminate their new risks. With their proprietary data and models, they promised to tell logistics companies how high to put their loading docks to avoid floods, consumer goods companies how to change their supply chains to avoid interruptions from storms, and banks whom to lend to and whom to avoid.

My insistence that this information should be public did not make these guys happy. I tried to explain to them that even they should want public infrastructure. People aren’t going to demand detailed analytics for a problem they don’t know exists. They didn’t agree. At one point, the CEO of one of the firms asked if he could buy Probable Futures. I told him that we would happily accept charitable contributions to support the work, but that the maps needed to stay public, easy to access, and free to anyone. He wasn’t interested in those terms.

Mooncussers were peculiar pirates. Instead of investing in a boat, crew, and guns, they waited on land near dangerous reefs and shoals. When the seas were wild, they would break into lighthouses and extinguish the lamp, hoping to induce a shipwreck and gather the riches that washed up on shore. They wanted to use their private knowledge of risk to seize opportunities. (They cussed the moon when it provided enough light for ships to still see the shore or the lighthouse tower.)

More and more companies are figuring out how to assess climate risk and are using their insights to help themselves. They aren’t as craven as mooncussers, but I don’t think they should feel great about what they’re doing. For example, executives from a few different American banks have told me that they are still issuing mortgages in risky locations only because they can immediately sell them to the mortgage market. Since they continue to “service” the mortgage (collect payments from the borrower), borrowers are getting the signal that the bank with all of its technology and market intelligence considers their home a safe investment. But in reality, the bank has shifted the risk into pools of capital whose investors aren’t looking for warning signs. Big private investment firms are doing similar things.

I’m all for competition in markets, but for a society to be prosperous and civilized, important information, especially about risks, needs to be easy for everyone to see. In his chapter about the amazing Bell Rock lighthouse off the coast of Scotland, which the Scots saw as a symbol of national enlightenment, Nancollas writes:

A rock lighthouse is a symbol of tolerance and altruism, of assistance to those in need regardless of their nationality. Taken too far, nationalism can lead to division, but a rock lighthouse offers a message of fellowship. It is a type of building that is not introspective, but outward-looking. It may monumentalize an enlightened Scotland, but Bell Rock itself enlightens the sea, which is indifferent to nationhood.

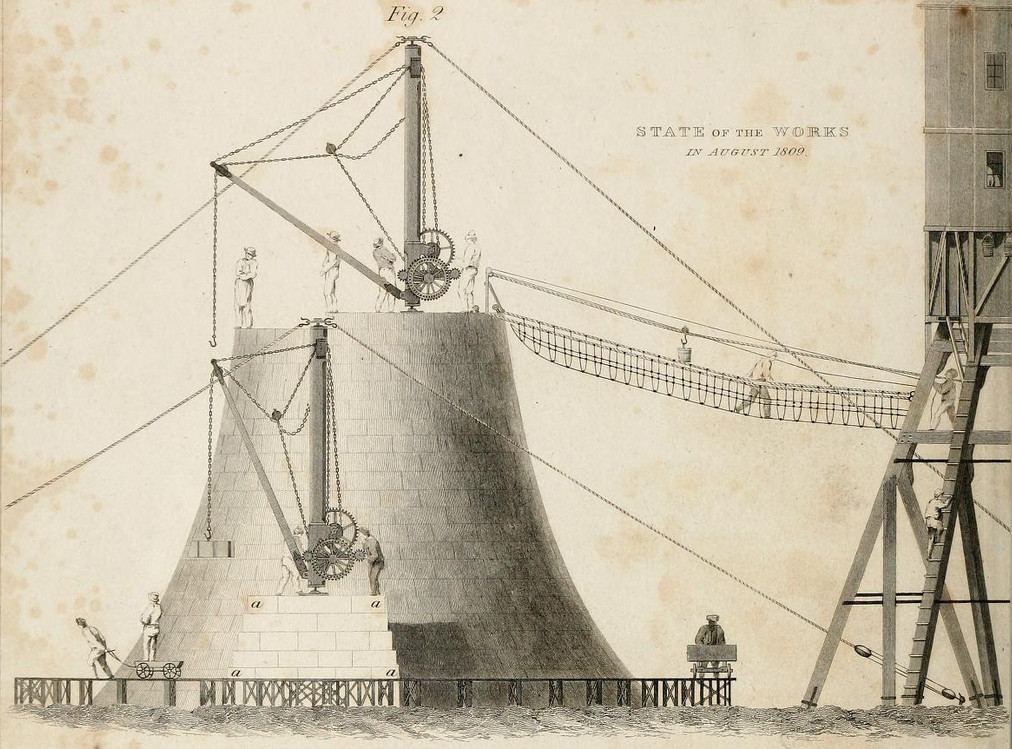

Bell Rock is indeed something to be proud of. Its builders could initially only work at low tide and had to invent several new devices to enable the construction. Consider this engraving of the project:

Here’s a picture of the final result. It contains a full living quarters for the keeper. (The netting had to be installed because birds found it so convenient.)

The great economist Ronald Coase tried to argue that a private market would build lighthouses if the incentives were right. His case is reasonable for lighthouses that draw people into a port. They are a service whose beneficiaries are easy to identify and charge. Fees on shipping vessels paid off the construction loans and supported the maintenance of such lighthouses. But a lighthouse that warns of a danger is really hard to value, and the value accrues to so many people that it’s not clear whom to charge for it. Simply put, lighthouses don’t have customers and don’t discriminate. To raise money for lighthouses, dour New England puritans resorted to lotteries to raise funds, while Bell Rock and all of the other British lighthouses designed to identify risks were paid for by general taxes.

Infrastructure that helps people see risks can be socially beneficial, but private, for-profit companies have no incentive to provide it. What kinds of infrastructure play this role in an era of rising temperatures, seas, and AI-generated information? I would like to make the case for well-maintained, freely accessible websites, including simple reporting, blogs, and maps.

Modern lighthouses

Consider your current location. Maybe you are in Galesburg, Illinois, or Harbin, China, or Bengaluru, India, all of which are far from the sea. Or perhaps you’re right near water, as in Naples, Italy, on the Tyrrhenian Sea or Naples, Florida, on the Gulf of Mexico or Naples, Maine, between Long Lake and Sebago Lake. Whatever your location, I can guarantee you that new risks are emerging around you. There are early signs: Maybe the plants in your garden don’t thrive the way they used to, or you now need air conditioning to make it through the night, or there is occasionally water in your basement, or a couple of months a year you need to use an air purifier indoors. And new, even bigger risks are coming: Perhaps the aquifer you depend on is likely to be inundated by sea water in the next 20 years, or summers are likely to have multiple days when it’s perilous to be outside, or the crops your community relies on will no longer grow there. Since you’re reading this essay, you may have noticed these things. But even if you haven’t, someone has. Someone knows. Do the folks in Vietnam know that some people are selling their property because of rising risks? Do they know that “the smart money” is leaving?

While my collaborators and I were building Probable Futures, another group was building FirstStreet Foundation, which was, at first, a nonprofit that sought to show people how climate change was likely to impact property in the U.S. Our organizations shared a goal to make climate data public and easy to access so that people could look at a map of their hometown and see the effects of climate change. There was one key difference: We judged it best to give broad, community-wide signals of increasing risk. We even restricted how much you could zoom in on our maps so that you had to see the broader regional context. The size of each cell on our maps was about the distance that a lighthouse throws its beam. FirstStreet believed that social change would happen when individual property owners were confronted with their own specific risks, so they invested huge amounts of money to create detailed flood and wildfire risk maps at a remarkably granular scale.

What happened over the next few years was nothing like the golden age of lighthouses. Venture capitalists who want to seize control of incipient climate adaptation markets offered tens of millions of dollars to turn the nonprofit public utility into a private service for hire. FirstStreet took a bunch of capital from investors to invest further in finely detailed physical and financial analysis for individual properties, became a for-profit corporation, and took down its extensive, detailed public maps.

After becoming a for-profit company, FirstStreet continued to offer some risk information without a transaction. It partnered with real estate brokerage websites like Zillow and Redfin to provide basic risk scores for properties that are currently for sale in the U.S., reserving all other information (including about buildings that aren’t currently on the market) for its customers. Zillow touted the data on their site, saying that potential buyers deserved to know the risks they might face if they bought a property. But Zillow’s data comes from realtors, and realtors have an incentive for every property to sell at the highest possible price, so they don’t like warning signs. And so, a few weeks ago, under pressure from a real estate brokerage company in California that provides market data, Zillow removed FirstStreet data from its site. The CEO of the California company offered as explanation: “The display of a probability of a specific home flooding this year, or in the next five years, can have a significant impact on the perceived desirability to purchase that property.” I agree with this fellow, but we come to different conclusions about the right way to address this problem.

FirstStreet’s homepage now says: “We exist to make the connection between climate and financial risk at scale for financial institutions, companies, and governments.” The “Products” section of its website offers services to asset owners, asset managers, real estate investors, banks, and corporations. In essence, the company promises its corporate customers safe passage through the perils posed by climate change for a fee.

I don’t have an opinion about what FirstStreet “should” do, and on balance I think it’s better for at least some people to have good risk information than for no one to, but I would like to point to a more civic model of modern lighthouse building. It comes from Western Australia, whose capital, Perth, is the most remote city in the world, squeezed between a desert and the ocean. And like most places on Earth that are in such positions (including many in California, North Africa, and the Middle East), climate change is dangerously disruptive. These places are like the original fertile crescent: narrow strips of land that are dry but not too dry, warm but not too hot, offering oasis-like microclimates that were home to specific species of flora and fauna.

Here is a map that shows the likelihood of extreme year-plus drought conditions in Australia. This is defined as dry conditions that would happen every 20 years (5% chance) in the past in each location:

The first map (0.5°C) shows the climate of the past, up to the year 2000, so every location has a 5% chance and everywhere is grey. The second map (1.0°C) shows how likely those prior drought conditions were back in the 2010s when the average atmospheric temperature crossed 1.0°C. The pea green color represents an 11–20% chance (i.e., every 5–10 years). The third map (1.5°C) is the atmosphere of today. Yellow is a 21–33% chance, and orange is 33–50%. We are on track to hit 2.0°C of warming in the between 2035 and 2045. The last two maps (2.5° and 3.0°C) are warnings of what the future will be like if we don’t stop adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. If and when we reach them are a function of our efforts to stop warming. On the present path, they are likely within the lifetime of a child who today is 10 years old.

Faced with increasing risks, the state government produced a climate adaptation strategy in 2023. Here is the introduction:

The science is clear. Western Australia’s climate has changed and further change is inevitable.

Western Australia is already experiencing the impacts of climate change, including more frequent and severe droughts, heat waves, high-risk bushfire weather, extreme rainfall events, and rising sea levels. These changes are affecting our communities, our infrastructure, our environment and water supplies, and all sectors of the state’s economy.

Many of these impacts will worsen as the climate continues to change and there is an urgent need to better prepare for the accelerating risks posed by this.

The document lists 37 actions that the state will take, including which department is responsible and a timeline. Here are the first eight actions:

- Expand the Climate Science Initiative to produce detailed climate projections for the north-west of Western Australia. (2028)

- Model the urban heat island effect of Perth’s future climate to provide better data for local adaptation planning. (2026)

- Investigate the impacts of marine heat waves on fisheries and the marine environment. (2027)

- Upgrade weather stations to better support pastoralists’ preparedness and response to extreme weather events in the Southern Rangelands. (2027)

- Model the impact of climate change on selected state-owned cultural buildings and recreational camps, and prioritise responses. (2024)

- Produce climate science communication materials, including visualisation tools, to make climate projections more accessible for communities, nonprofit organisations and businesses. (2028)

- Develop and promote climate change communications materials to build community awareness of climate risks and practical options for responding. (2028)

- Collaborate with the Bureau of Meteorology and Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) to understand and communicate the impact of climate change on Western Australia’s water resources. (2025)

I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that Western Australia is good at lighthouse-like thinking given that it’s home to the awesome-looking Bunbury Lighthouse:

We are all sailors now

In school I learned about adventurers. Some were sponsored by administrations that sought wealth, but as I learn more about the history of civilization, I keep being surprised by the variety of motivations that people had for doing things. For example, my grandfather joined the Navy at 17 in part because the orphanage from which he escaped would be unable to track him down on a boat.

Sailors operate under codes of conduct regarding signalling, risk, and mutual aid. Regardless of their reason for being at sea, sailors have legal and moral duties to help each other out in times of distress. I’ve been reading rules for sailing races, cruise ship operators, and even yacht rental operations in the United Arab Emirates. All of them say:

The primary responsibility of a vessel operator assisting a boat in distress is to ensure safety by approaching carefully, establishing communication, signaling for help, offering assistance, and staying until help arrives without endangering their own vessel or passengers.

In crises, we tend to do this on land as well. We help out, put things on hold, temporarily look away from the bottom line or our most individualistic needs. Sometimes people fail in these settings, acting cravenly or even opportunistically, but more often, we are our better selves. In her book A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster, Rebecca Solnit documents how people often come together after crashes, earthquakes, floods, etc., and work together with altruism, resourcefulness, and generosity. In fact, the history of mooncussers indicates that they often risked their own lives to save sailors imperiled by crashes they themselves enabled.

The question we face now is whether we can act that way before the wrecks, losses, and crises. It’s not easy. We don’t have any incentives to do it other than that it’s a good thing to do. And yet, there is evidence all around us that these things can be done, even if there will never be a measure of the crashes and crises avoided. Right now, people are undertaking civic actions that will benefit other people they will never meet. You can participate by sharing your and your organizations’ stories of risk, highlighting good ways to reduce those risks, and supporting the creation of lighthouses by your community or other organizations (including this one). If you have a story you’d like to share with Probable Futures, please send it to us. We are collecting them.

If you need a little inspiration, I am happy to share the story of Bill, a guy I barely know.

In the summer, my wife and I go to a small public park on Cape Ann to play tennis. We often see two guys in their seventies who seem to battle each other every day. Eventually we got to know a bit about them. Joe and Bill were both teachers at Rockport High School and they live next to each other across the street from the school. One day last summer, as they were leaving the court, I asked Bill what he had planned for the rest of the day. “I’m kayaking out to Thacher Island. A group of us go out there every weekend in the summer. We are restoring the lightkeeper’s house.”

I wish you well and hope that 2026 brings joyful light to you and yours.

Onward,

Spencer