I hope that you enjoyed a vacation during the season that formally ends today. Leaving home can open our minds and clarify what is valuable in life. One certainly doesn’t need to cross an ocean to see things anew, but as my wife, Lisa, and I spent time in Europe, I became more convinced that living well in a changing climate will require all of us to open our minds and seriously consider our values.

French lessons

The Probable Futures team is made up of people who love art, architecture, food, culture, technology, sports, etc., and want to help everyone have access to them. A big part of the initiative’s message is: “The stabilization of global temperatures starting around 10,000 BCE enabled settlement, planning, investment, and elaborate, specialized societies.”

When making this point in presentations, I often show a photo of a wheat field and transition to an aerial view of the Champs Elysées that runs down the center of Paris:

It’s a cinematic and poetic visual transition. Stability enabled agriculture; agriculture enabled cities…et voilà, Paris!

Many of the reasons that more people vacate their everyday lives to go to France than to any other country are represented in that image: the beautiful buildings, the compelling urban geometry, the Tuileries gardens in the mid-distance, the cafés along the streets, and the Louvre Museum in the background, filled with invaluable art and artifacts.

In presentations, I use this image to show Paris’s vulnerability: “Almost none of the buildings you see here have air-conditioning, and underneath the Champs Elysées is the main artery of Paris’s storm sewer, which was not built for the intensity of rains that climate change will bring. Paris was built on a plan, and that plan assumed the climate would remain stable forever.” It uses information that people aren’t used to seeing as data: A beautiful image of “The City of Lights” is transformed into a map of heat and flood risk.

The image also contains the complicated legacies left behind from periods of extreme inequality. The Louvre is now a museum that anyone can enter, but it wasn’t built in that spirit. Over centuries, monarchs who believed themselves to be the sole legitimate rulers ordered the construction of a vast complex of fortresses and palaces, which they filled with more beautiful, valuable objects than they could ever look at. The nearby tree-lined streets, with their handsome stone facades and scenic parks that beguile the visitor and inspire urban planners, were mandated by an emperor. One of the things I love about France is how the beautiful artifacts of a wrong-headed society have been incorporated into a more equal, democratic, humane way of living.

Touring and tourism

In 1992, Lisa and I traveled around Europe by rail, sleeping in a tent and eating mostly bread, salami, and oranges. It was a tour in the centuries-long tradition of the Grand Tour that, first for young British nobles and subsequently for wealthy American industrialists, was considered a rite of passage. The idea was that to be cultured, one needed to visit France, Italy, and perhaps Greece to gain appreciation for the finer things and learn about the ancient roots of Western civilization. Despite (or perhaps because of) our frugality, our tour had the desired effect. In Florence, for example, we spent our days taking in the artistic and architectural legacy financed by the Medici family and our evenings looking out over the city from our hillside campground. I suspect those experiences strengthened our shared conviction that everyone should have beautiful things in their lives.

Lisa and I did not know if we would ever see these places again, but we wound up incredibly fortunate, and have been able to return to Europe for work and vacation. When we go away now, we prefer to stay somewhere for a week or two with friends so we can get a feel for the place, shop in local produce markets, and take in not only extraordinary things but also the mundane. We began planning this summer’s vacation over a year ago, and I wanted to be sure to avoid extremely hot weather.

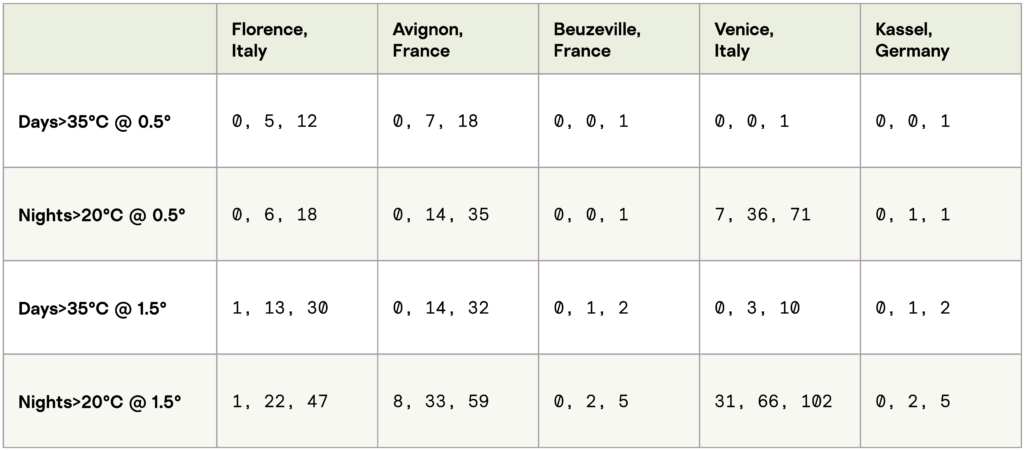

Probable Futures is a fantastic planning resource. I used the maps of temperature to see the likelihood of days above 35°C (95°F) and nights that wouldn’t drop below 20°C (68°F). Since global temperatures are now around 1.2°C above the pre-industrial average, I consulted the maps of 1.5°C of warming.

Below are the results for a few places we have been in the past and where we went this summer. I include the results for 0.5°C as comparison, which was roughly the global average temperature during our 1992 tour. The values in each cell are the number of days above each threshold in a relatively cool year (10th percentile), a median year (50th percentile), and a relatively warm year (90th percentile):

You can see from the first two rows why no Europeans had air-conditioning. Across France, Italy, and Germany, hot days were rare, and nights tended to cool off. The last two rows show that hot days and warm nights are much more likely. We rented a centuries-old house near Beuzeville in the French region of Normandy. We packed a mix of cool and warm-weather clothing and began reading books and watching shows and movies set nearby.

The climate of culture

Books and videos allow us to vacate our everyday without leaving familiar surroundings. During the pandemic, many people have gravitated to shows that bring foreign lands to life. The actor and director Stanley Tucci began filming a show called Searching for Italy in early 2020. In the opening credits, Tucci announces, “I’m traveling across Italy to discover how the food in each of this country’s 20 regions is as unique as the people and their past.”

Production was hampered by Covid, but over the course of 2020 and 2021, Tucci and his team managed to visit seven of the 20 regions, and people who were stuck in their homes elsewhere in the world were glad to ride along, even if only on screen. I watched with some of the same joy and escapism as the millions of others who made it a hit, but I also sensed that I was inspecting a time capsule from the last days of the traditions Tucci was celebrating.

Each episode focuses on food and its relationship to the region’s history. In every case, a distinct local climate makes its food special. Take Tucci’s introduction to the Bologna episode, for example:

Bologna is the capital of Emilia-Romagna, a wealthy region that straddles Italy and is cocooned between the Adriatic Sea and the Apennine Mountains. It’s a lush land of fertile river valleys stuffed with livestock and billowing soft wheat. No wonder it has bred one of the world’s best chefs.

Viewers learn about true Parmesan cheese (Parmigiano Reggiano), authentic Parma ham, and legitimate balsamic vinegar from Modena. The Emilia-Romagna region is home to more DOP (Denominazione d’Origine Protetta) foods than any other. Such foods are protected by Italian regulations. The food and drink can only be made with particular methods, in a particular place, in order to be the real thing. Why? Because those methods, in those places, produced something extraordinarily delicious. San Marzano tomatoes only come from one place; Barolo wines come from Nebbiolo grapes that are named for the specific fog (la nebbia in Italian) that rolls through the fields where they grow; a cool seasonal breeze is the magic ingredient in a prized cured meat. You can watch Tucci’s expressive face swoon, melt, and giggle as he tastes things that took centuries of experimentation—and a stable climate—to perfect.

I am curious what Tucci will do in the forthcoming episodes of his show, and whether he will return to Emilia-Romagna, because as he makes his tour, the rapidly approaching future is crashing into each region’s traditions. This summer, the “lush land of fertile river valleys stuffed with livestock and billowing with soft wheat” were very hot and very dry. The Po River, which irrigates the region, was catastrophically low because there was less snow and rain upriver, and higher temperatures pulled more moisture from the tributaries, soil, plants, and animals along its banks. The cows that produce Parmigiano Reggiano cheese require 100–150 liters of water per day in an “average” year and feed on grains grown nearby. Less water, more heat, or a different feed, and the cheese is not the same. Auditors and police protect DOP producers from imitators, but there is no protection from the atmosphere.

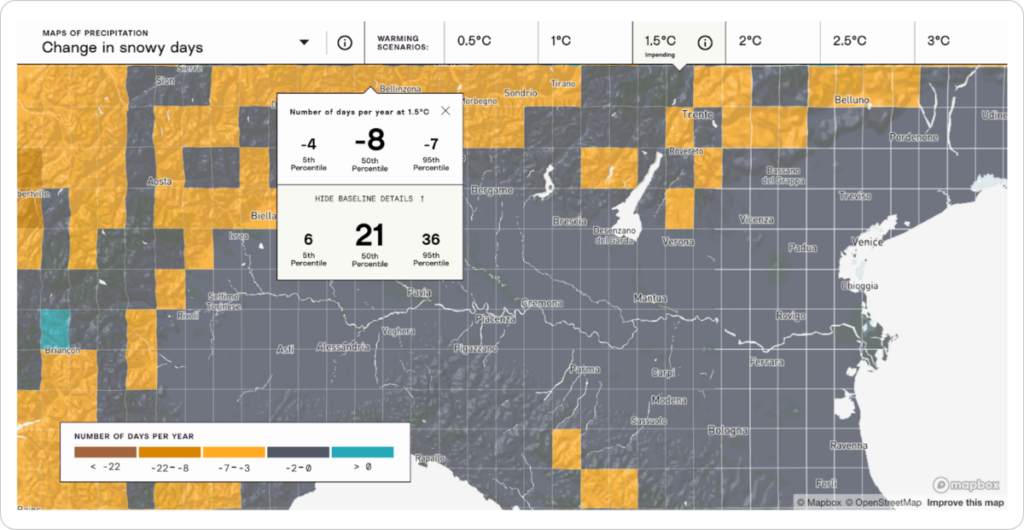

In this Probable Futures map of Change in Snowy Days, you can see the Po River’s tributaries feeding it along its eastward journey to the Adriatic.

I have selected the cell that contains the town of Locarno, Switzerland, on the shore of Lake Maggiore. The boxes indicate that at 1.5°C of global warming, the number of snowy days in Locarno will be lower than when the average global temperature was 0.5°C (1971–2000). In a median year, there will be eight fewer snowy days, so instead of the historical 21, there will be 13. A warm (5th percentile) year will lose four of its six snowy days. I looked at Locarno’s weather this past winter, and there was one day of snow last December and one night with light snow in January. That was it. In February, there were several days above 15°C (60°F) in Locarno.

Less snow and warmer winter weather mean less snowmelt to fill the rivers in spring and summer. Tucci didn’t explain that Parmesan cheese is born in the Italian, Swiss, and French Alps, but it is.

Tucci’s show is excellent, partly thanks to his charm and the beautiful imagery, but also because of the way he helps the viewer understand that while the cheese or ham or pasta is delicious, the special thing is the culture that the people have built around those foods, from the farmers who grow the raw materials to the artisans who process it to the chefs who make it sing. I found just one segment of the show discordant: He attends an auction at which a bidder in Hong Kong pays €100,000 for a large white truffle from Piedmont. In this harsh setting, the food is valuable because people somewhere else will pay for it.

After the auction, Tucci drives into the mountains to meet a truffle hunter. The voice-over describes the Langhe area where white truffles grow:

Here conditions are perfect. Warm air from the south pushes back cold currents from the Alps, and summer rainfall feeds the mineral-rich soil.

I find the verb tense in descriptions like this particularly poignant. “Are,” “pushes,” and “feeds” all imply a habitual state: This place has been like this, is like this now, and will stay that way. A grammatical fine point may seem nitpicky, but this certainty in describing places is a product of a stable climate. We use language this way because we assume that local weather is stable. How different would it feel for Tucci to say: “Historically, conditions were perfect. Warm air from the south pushed back cold currents from the Alps, and summer rainfall fed the mineral-rich soil”?

The truffle hunter, Igor Bianchi, is spectacular. His beard is parted in the middle, and rubber bands turn each side into a chain of white puffs. Bianchi and his border collies, Lola and Susy, lead Tucci into a patch of woods where the dogs will hopefully sniff out what Tucci calls “white gold.” They don’t find any. Tucci says to the camera, “The truffles are being coy.” In voice-over, however, he tells us that climate change has led to less summer rainfall and thus fewer truffles in the fall.

Bianchi takes Tucci back to his house and cooks him an egg with truffle on a propane stove in his garage. He tells Tucci that back in the 1970s, white truffles were abundant. Tucci asks whether perhaps the valuable fungi can be cultivated, implicitly asking if farmers can outfox nature. Bianchi explains that it has been tried for 30 years without success, and that he’s happy about that, because exploring the woods to look for special mushrooms is fun.

Economic models are unlikely to detect the value of white truffles when tallying the costs of climate change. Even if they do deduct them from Italian GDP, the hypothetical workers and consumers will simply switch to making or eating (or, more accurately, selling or buying) something else, because in economics, all consumption is fungible. I am sure, however, that a world without Igors, magical aromas, and mysterious fungi hidden in the woods is a poorer one.

Feeling the heat

The historical average high temperature in mid-July in Beuzeville was 21°C (71°F). The first three days after we arrived in the old house, temperatures were around 40°C (104°F). We did our best to adapt. We developed a protocol for when to close windows and shutters and when to open them. We ate dinner late and moved beds to the center of rooms to maximize airflow. It was okay, mostly because we were on vacation and the weather forecast told us it would end. Indeed, on our fourth day, it rained for two hours and we felt liberated. The brief showers ushered in a more comfortable regime, but temperatures didn’t go back to “normal.” Over the next ten days in Normandy, we enjoyed weather that would have been common in Southern France or Spain thirty years ago.

Normandy is renowned for foods made from apples, buckwheat, and dairy. It was historically too cold for grapes, so the local drink is cider in various forms, including a spirit called calvados. Like Champagne and Camembert, calvados can only be made in one area using certain techniques and is protected by France’s version of DOP, AOC (Appellation d’Origine Controllée). On a tour of a local estate, we learned that casks of calvados must be kept at ambient temperatures, as climate control is against the rules.

Pont-l’Eveque is the eponymous source of one of France’s great cheeses. As we drove past it and other small towns in our air-conditioned car, we sympathized with the cows huddled under lone trees and against the edges of fields where hedges offered some shade. We also worried about the people in homes and businesses whose buildings, products, and recipes were unprepared for this heat.

We got to know a chef who had recently moved back to the region after working around the world. He served us local fish garnished with a delicious pickled seaweed that he and his mother had gathered along the coast. As the heat finally eased after 10 p.m., he asked what I did for work, and I told him about Probable Futures. I explained how stable climate patterns were an essential ingredient in the foods he celebrated and that we were witnessing climate change as those patterns broke. He told me that most of his friends are farmers and that more frequent extreme weather deepens his worries about their financial and emotional well-being. We didn’t meet any farmers, in part because the ones near us were harvesting their wheat after midnight when the temperatures were less harsh.

After Normandy, we went to Venice, Italy, so that Lisa, who directs a free contemporary art museum, could take in an art exhibition. We took a train through France and across Northern Italy, staring out at fields of stunted, shriveled plants. We arrived in Venice and were hit with a wall of hot, damp air. Lisa has stayed several times in an apartment owned by a local couple. This time, as Manuel met us on the banks of the Grand Canal, all three of us sweat through our clothes in a matter of minutes. “It has never been like this,” he said. When we got to the building, he opened the door and said, “The first thing you need to know is about the electricity.”

Venice has possibly received more climate-related attention than any other city due to its vulnerability to sea level rise, but the city is unprepared for heat. Manuel explained that as more people in the apartment building installed air-conditioning, it was increasingly common for the electricity to fail. He showed us the fuse box and gave us elaborate instructions on which appliances could be used together and which could not. Later that evening, I went to probablefutures.org and checked to see if Manuel was right about it never being this hot and humid in Venice.

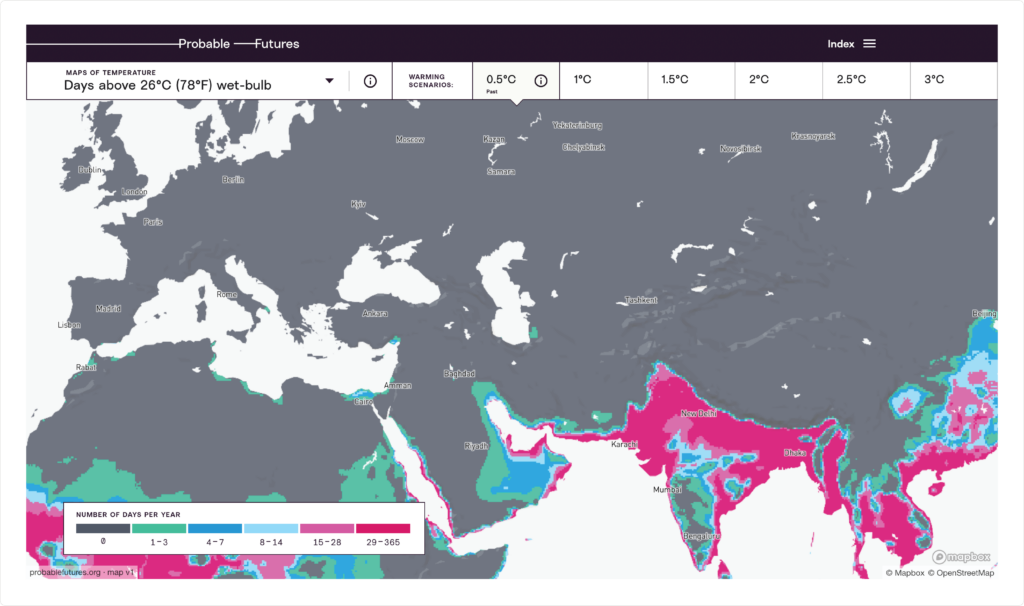

Wet bulb temperature is measured by wrapping a thermometer in a thin, damp cloth. If the relative humidity is 99%, the water in the cloth won’t evaporate, and the thermometer will give the same reading as a plain thermometer. If the air is extremely dry, the cloth’s moisture will evaporate quickly, cooling the cloth, and the wrapped thermometer will have a much lower reading. When air is warm and humid enough, sweating doesn’t cool the human body down, putting great strain on the cardiovascular system.

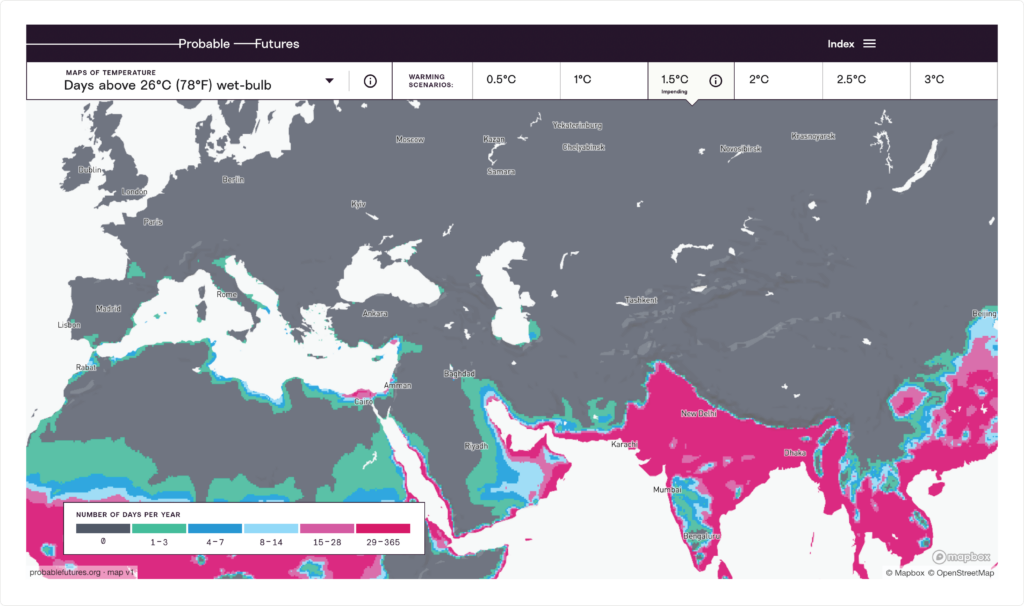

I calculated that the wet bulb temperature in Venice was likely to be around 26°C during the next few days as we walked around the city. Looking at Probable Futures maps of heat and humidity, I saw that Manuel was probably correct: 26°C wet bulb likely never happened before in Venice. Here is a map of the expected number of days above 26°C wet bulb when global temperatures were 0.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Northern Italy had zero such days.

Global climate change has rendered Venice’s local climate more like that of its ancient trading partner to the southeast: Alexandria, Egypt. Alexandria is now like Qatar was, and Qatar’s summer at 1.5°C of warming has no historical comparison:

We need to prepare

I started this endeavor about three years ago, largely because I couldn’t get leaders in business and finance—today’s aristocracy—to even talk about climate change, let alone act on it. I hoped that providing vivid, resonant examples of the losses and suffering that climate change would bring—in both prosperous and poor places—might motivate action.

Now the beneficiaries of an inequality that resembles the age of Louis XIV are starting to sense that if the system that enriched them fails to address some problems, they will lose at least their status. This is real progress, and I’m delighted that investors and consultants have concluded that clean energy is a potential investment bonanza and that climate change can help the economy. I still see scant evidence, however, that people want to talk about actual climate change. The US’s new climate bill is fantastic news, but it’s noteworthy that its official name is the Inflation Reduction Act.

I get it—we don’t want to change the verb tense we use when describing a place, let alone accept that this year’s hot weather will be anomalously cool in the future. But even rich countries are more vulnerable than most people think. A stable climate didn’t just enable the development of delicious foods; it made everything easier, including governing. The Italian government has changed leaders 17 times in 32 years and owes 150% of its GDP in debts, despite having had an ideal climate. As if on cue, the current Prime Minister resigned during our trip after less than 2 years on the job.

Climate change is sometimes called a “threat multiplier,” and every society faces threats. If we don’t use the insights of climate science to prepare infrastructure, agriculture, and all other forms of culture, the threats may become unmanageable. Thankfully, we have tools.

I am proud to announce the third volume of Probable Futures: Land. It builds on the previous two volumes (Heat and Water) and offers explanations and explorations of the ways in which local climates are changing and moving everywhere on earth. There are pages about complexity, soil, and how people have transformed the surface of the planet, especially to produce food. There is a particular focus on how a warmer atmosphere makes extremely dry weather more likely in much of the world.

The Standardized Precipitation and Evapotranspiration Index (SPEI) takes precipitation, temperature, relative humidity, and wind data to model how weather will affect terrestrial moisture (in soil, plants, lakes, etc.). The US Drought Monitor describes the expected consequences of extreme drought as: “major crop/pasture losses and widespread water shortages or restrictions.”

“Extreme” is defined locally, so a drought in the Amazon rainforest will be wetter than a drought in Italy. What matters, though, is that organisms, plants, animals, people, infrastructure, and culture have evolved during the past millennia to be perfectly suited to the stable patterns that prevailed until recently. A severe drought in Italy is brutal for Italy’s living things, and a severe drought in the Amazon is brutal for the Amazon’s many more living things.

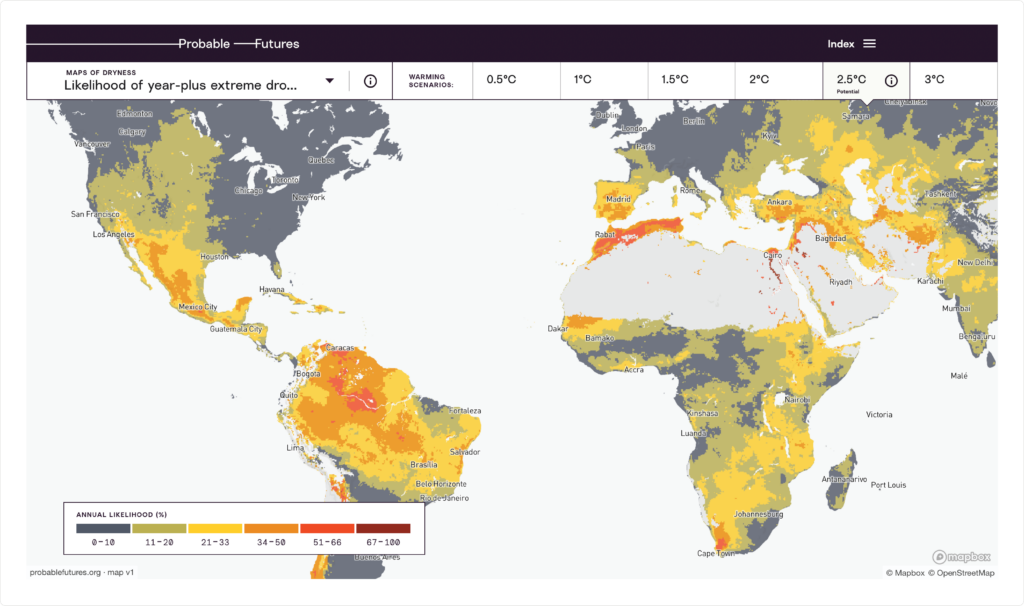

As in previous volumes, our maps take 1971–2000 (0.5°C) as our baseline and show how much more likely extreme dryness becomes at higher levels of warming. Where higher levels of warming have no effect, the cells are gray.

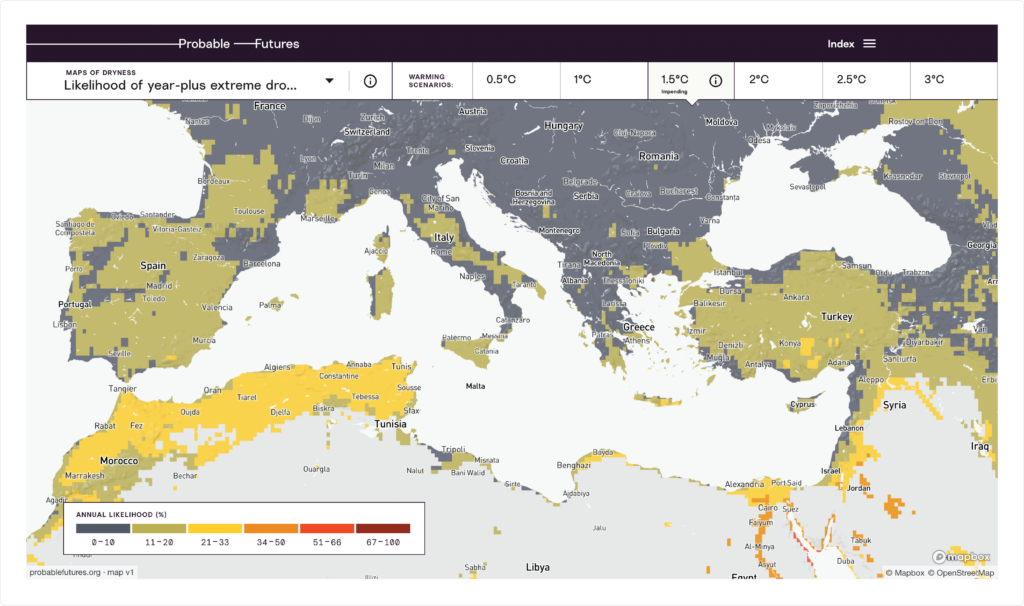

Below is a map of the likelihood of a year-plus extreme drought around the Mediterranean Sea at 1.5°C. People should be expecting extreme drought more than once a decade in much of Italy. Places that were already extremely arid in the baseline period cannot get drier. Such locations are shaded a pale gray.

Last year, much of Europe was coping with floods, but this year it has been experiencing drought. This is what climate models have told us to expect. On average, most of Europe is expected to have about the same amount of precipitation as the atmosphere warms. It’s just that “average” won’t happen very often, and during dry periods, warmer air temperatures will pull more and more moisture from the land.

Droughts, however, are temporary by definition. As temperatures move further from stability, what was rare can endure. You may have noticed at 1.5°C of warming, the thin strip of fertile land between the Sahara in North Africa and the Mediterranean Sea was mostly yellow. Below is a wider view of the world that awaits us if we reach 2.5°C of warming. The world’s desert borderlands—that over a billion people call home—are yellow, orange, or red, indicating desert expansion. At the other climatic extreme, the Amazon rainforest, home to more life than anywhere on Earth, will experience what used to be called “extreme drought” 34-67% of the time. At those levels, the correct term is “aridification”: a permanently drier climate.

Finding beauty in the everyday

I am skeptical of and frustrated by the billionaires who promise us “breakthroughs” and win-win-win outcomes as well as the economists whose models reassure us that climate change will only slightly diminish our infinite future abundance. Somehow, both have “pivoted” to incorporate climate change without either accepting limits or wondering if perhaps the ecological destruction we are now trying to fix is the byproduct of the system that enriched them. Instead of adapting, some suggest just going elsewhere (the Land volume has a section on Mars, in case you’re thinking of it as Plan B). What I think bothers me most, however, is how lifeless their numerical, financial views of life are. As a tonic, I suggest reading Rebecca Solnit’s new book, Orwell’s Roses.

Solnit writes about art, culture, justice, and nature. I have learned a great deal from her, including the invaluable distinction between optimism and hope. George Orwell has also been an inspiration. All of his writing is critical and purposeful, and to that end, he tried his very best to make it compelling, imaginative, and enjoyable reading. Our team has done what I consider to be heroic work in making Probable Futures both useful and beautiful with the hope that people who experience it will both sense the care that went into it and better learn from it.

It turns out that while doing everything he could to fight fascism, Orwell planted roses. He also planted fruit trees, vegetables, and other kinds of flowers next to a small house he rented. Solnit, who also admires Orwell, was so struck by this fact that she went to see the rose bushes, now nearly 100 years old. Orwell’s Roses is about many things, including Orwell’s remarkable life, but the central theme is the value of beauty and nature, even—perhaps especially—when society is in trouble. She recounts the story of a war crimes lawyer in the Hague who visited Vermeer paintings between trials to sustain him. The artist Zoe Leonard tells Solnit that she thought her images of clouds felt trivial and perhaps wasteful during the AIDS crisis but that her friend implored her to keep making beautiful things as a reminder of what they were fighting for.

David was right. You go through all of the fighting not because you want to fight, but because you want to get somewhere as a people. You want to help create a world where you can sit around and think about clouds. That should be our right as human beings.

The clouds in Normandy were spectacular. Something about the border of the ocean and the land mixed in with the contrail of the planes flying to and from North America gave the skies depth and texture. Every day, I spent time admiring the clouds. Sometimes I stopped our car to get out and take a picture. Here’s one I captured after a wrong turn leaving Monet’s home in Giverny:

Those first two hours of rain were the only precipitation we encountered over the month we were away. The weather was frightening, but many experiences were encouraging. Perhaps most significantly, we witnessed successful planning in action. In 2003, a similar heat wave struck northern France, and thousands of people died in their homes, partly because of a lack of air-conditioning but largely because people were unaware of the risk and did not look out for or check in on elderly, poor, and sick neighbors. After that terrible experience, the French government put together a heat emergency system. During this summer’s heat wave, the alert was activated in France, and almost no one died.

While we were away, we received texts from Boston’s own new heat emergency system, but cooler weather has now arrived. I hope that the coming season is kind to you and the living things around you. I hope you have a chance to travel outside your everyday, whether by foot, vehicle, book, video, or other means. I also hope you will check out the latest on probablefutures.org. I am proud of our team and the work they have all done. It is a valuable, useful, beautiful resource that we hope people will use to spark their imaginations, strengthen their communities, and even plan their vacations.

Onward,

Spencer

Books

Orwell’s Roses by Rebecca Solnit

Why I Write by George Orwell

The Remains of the Day by Kazuo Ishiguro is a meditation on what constitutes excellent work and the role of service. I found myself thinking about it in relation to modern talk of corporate responsibility. Rereading it was rewarding.

Movie

A funny, heartfelt movie about family, food, and summer in Italy: Mid-August Lunch