I might have eaten a hundred peaches this summer. Every week my wife, Lisa, and I would go to Lattof Farm Stand hoping to find them. In late June, small, firm ones from New Jersey appeared. They were juicy and sweet, with thin skins. Starting in mid-July, local peaches started coming in. They were delicious in their own ways, a bit more firm and tart, bigger, and with a snappier skin. Importantly, once there were local peaches, there were peach pies from Mann Orchards. As the terse, weathered, wiry proprietor of Lattof’s said about the owner of Mann’s, “That man does not know how to make a bad pie.” So for the rest of the season, we would buy a bag of peaches and a peach pie every week. It was a good summer.

A couple of years ago, no stone fruits grew in New England. Peach, nectarine, plum, and apricot trees in the region had been fooled into flowering in February because of record warm weather. When winter resumed for another few weeks, the buds died, ruining the harvest. This year, the record-hot global atmosphere largely spared New England, and plants and people enjoyed old-fashioned winter, spring, and summer temperatures. Still, each time we went to the farm stand, we worried there wouldn’t be peaches. They couldn’t be taken for granted.

As I started my days with a piece of pie, I found myself appreciating the process and values required to plant and care for an orchard. The commitment. The patience. The reward. A relationship between land, people, and plants that could continue in perpetuity. I also wished that climate business people would think of their products more like orchards and consider the long-term viability of their products in the context of a changing, often more challenging climate. Unfortunately, very few are doing so.

Just down the road from Lattof’s, less than half a mile from the Atlantic Ocean, a standard, three-blade windmill towers above the city of Gloucester, spinning when the wind blows, sending power to the local grid. Next to it stands another three-blade windmill that no longer moves, no matter how hard the wind pushes it. Down in the industrial park below sits the base of a third windmill that was taken down this spring, two years after it stopped working when a blade fell off. Despite public requests, the company that owns the windmills has refused to share information about why the two broken windmills stopped working. I have a hunch that, as with the free EV charger at Gloucester City Hall whose base has rusted away over just five years, everyone was so excited to sell and install them that they didn’t check to see if the designs or materials suited the local weather conditions or how those conditions might change as the atmosphere warmed.

Idle windmills, over- or under-powered heat pumps, broken solar panels, and malfunctioning EV chargers are unprofitable for their owners. They are also ugly and dispiriting. If people in climate businesses would pay more attention to actual changes in local climates and focus on longevity, quality, and aesthetics, the fruits of their labor would earn the public’s trust and higher returns on capital over time. If all of us grow more interested in businesses like orchards, which earn modest returns but make life delicious, we may also be able to avoid living in a world without peaches.

What nature gave us for free

Imagine deciding to plant an orchard. You buy land, clear it, choose a specific variety of tree, and plant tiny seedlings or even tinier seeds or pits 12 to 25 feet from one another. You will not taste—let alone sell—fruit anytime soon. Instead, you will nurse these small, vulnerable plants into juvenile trees over years, watering, sheltering them from storms, removing competing plants, and discouraging pests. If you are fortunate, after several years, your young trees will offer their first fruits, and you will find out if the dates, olives, figs, or peaches are as tasty and hearty as you had hoped. Still, the trees won’t be mature for another several years. It’s a low return on capital and effort. You’re in the red for a long time.

Settlement and agriculture began in Mesopotamia and the Levant (which contains modern-day Syria, Israel, Jordan, Palestine, and Cyprus), with communities cultivating cereal grasses like barley and wheat, followed over time by legumes like chickpeas and lentils. These plants grow quickly and yield every year. They don’t require much planning, and they can be rotated with others. A community that is operating on a short, urgent time horizon can turn to these crops for basic nutrition. Archaeological evidence indicates that the first settled communities formed about 12,000 years ago. There is no evidence of orchards for the next 5,000 years. Why did it take so long? A paper published in 2022 that documents the first evidence of fruit tree cultivation (olives and figs) explains:

Fruit tree cultivation is a long-term investment with a relatively delayed return. It is possible that a fruit tree plantation would not assume its full yield potential within the short adult lifetime of the planter 7,000 years ago, due to the long juvenile period of some of the fruit tree types, even if clonally propagated. In addition, fruit trees cannot be rotated like annual plants between different plots, and therefore special care must be taken when allocating the land for a fruit tree plantation. Furthermore, unlike annual grain crops, orchards are long-lived and, therefore, have considerable implications for land ownership and heritage systems.

All these features are calling for more elaborate social contracts and institutions.

Orchards only make sense if a society has “elaborate social contracts and institutions” so that people can make long-term capital investments with confidence that they or their descendants will enjoy the fruits of their labor far into the future. As one of the coauthors explained in an interview, “As a whole, the findings indicate wealth, and early steps toward the formation of a complex multilevel society, with the class of farmers supplemented by classes of clerks and merchants.”

There’s one more concern: Even if your society of specialists, merchants, and clerks is well governed and offers legal assurances for the long term, planting an orchard still only makes sense if you believe the weather will stay the same. Until recently, that wasn’t a concern.

Over 7,000 years in the Levant, during dramatic societal change, farmers there continued growing olives and figs because the local climate stayed consistent. Here’s a graph of atmospheric temperature going back to the dawn of civilization:

It wasn’t just farmers who trusted that the climate would be stable. So did architects, builders, engineers, regulators, insurers, lenders, homeowners, and all the rest of us.

I spent the summer reading academic research and news articles about olives, lychees, apples, peaches, and all kinds of other fruits. In parallel, I read engineering and material science journals. Lychee and apple farms are similar to wind farms, solar farms, and all kinds of other green investments: They require up-front investments to earn gradual returns over many years, and they can be ruined by weather for which they are ill-suited.

“Winning isn’t everything; it’s the only thing.”

Thousands of years after people first specialized in metallurgy, textiles, trade, and cultivating fruit trees, new specializations emerged: climate business and climate philanthropy. Although Probable Futures is a nonprofit organization that often intersects with business, I am uneasy with the implicit principles and frameworks that hold these sectors together.

Explicitly, the message of most climate business and philanthropy is that we have to decarbonize to save the planet. Implicitly, their pitch is, “If we deliver you food, shelter, heat, light, transportation, and consumer goods without emissions, you can continue ignoring the physical, natural world around you.” The most strident version of this message to consumers and the public is, “If we sell you all of the goods and services you now consume but with green inputs, you will spend less money, and you will have better products, and we will solve climate change so you don’t have to pay attention to it.” Win-win-win without learning about your local climate or how it’s changing.

The same day I send this letter, Climate Week NYC begins. The marquee event, hosted by Climate Group since 2009, is invite-only for leaders in climate action, with 32 sessions over four days. The theme of this year’s event is “It’s Time.” Past editions have had similar themes: “Driving Climate Action Fast” and “Getting It Done.” In 2019, the theme was “The Climate Decade Starts Now.” In each case, the “Action” or “It” is decarbonization.

The Climate Group’s 2024 sessions will be about solar, wind, electric vehicles, methane, steel, concrete, grids, subsidies, and taxes. There is a session on sustainable food. In this case, what constitutes “sustainable food” has nothing to do with what farmers can sustainably grow, but rather how government purchasing of food can help reduce emissions.

Similarly, a session about health isn’t about how to lessen the health impacts of climate change; first, it looks at the carbon emissions of the healthcare industry, and second, it asks how bad health outcomes can be incorporated in storytelling to inspire public support for decarbonization.

Let me be clear: It is urgent to reduce emissions. I am all for innovation, investments, conferences, and marketing that can get individuals and companies to buy goods and services that heat the atmosphere less. I even think using public health stories to motivate regulation is a good idea. The problem is, like most gatherings of climate business people, the conference theme largely ignores the fact that the climate has already changed and will certainly change further. The theme focuses on how to stop warming (which is often called mitigation), not how to live with and prepare for it (which is called adaptation). But mitigation without adaptation is a bad recipe.

For thousands of years, it was sensible for farmers in the Levant and everywhere else in the world to assume that the past climate would serve as a guide. Strangely, businesses that are motivated by climate change currently lack this sensibility, and instead often rely on building codes and engineering standards that were set in the past and assume future stability. In fact, climate business people often don’t want to talk about risk, especially risk that will ultimately be borne by their customers.

Selling good vibes

When I first started sharing maps with the specific local projections of drought, heat, wildfire, and other variables with people in 2018 and 2019, there was a divide between audiences. People outside the climate business community would say, “That was fascinating!” while people inside it would say, “Well, that was depressing.” One example is perfectly representative.

I spoke at a conference in 2019 hosted by the Urban Land Institute, the largest organization of building-related professions (architects, planners, builders, investors, etc.) in the world. Afterward, a man came up to me. He told me that he had spent several years as a property developer and had recently been hired by one of the internet giants to build and manage its burgeoning real estate portfolio. “I had never thought about how insurance and lending are going to dry up in risky places. People need to know about this. Would you be willing to talk with the head of sustainability at my company?” he asked. I said I’d be happy to.

A few weeks later, the three of us got together on a video conference, and the real estate guy kicked things off by saying how informative and persuasive he had found my work and that he had become convinced that financial markets were going to change. The sustainability person, whose cat was luxuriating on screen, said, “Our theory of change is that bad news just shuts people down. We don’t share any bad news. We are only interested in solutions.” I watched the face of the real estate guy fall. He had come to his new Silicon Valley boss, saying, “I was convinced by this,” only for her to say, “This isn’t the kind of thing that convinces people.” (When people say something like that now, I recommend my colleague Alison Smart’s essay on what works and doesn’t in climate communication.)

I get it. It’s more fun to sell salvation and optimism than it is to sell complexity, risk, compromise, and loss reduction. (That’s why we built Probable Futures as a nonprofit.)

Selling long-term power with short-term money

There’s a second, rational reason why climate businesses focus on decarbonization over adaptation: Selling power has almost always been a good business. There are real, important, vexing challenges to get people to switch to a heat pump from a gas furnace or to an electric vehicle from an internal combustion engine vehicle or to solar panels from a coal power plant or even to fertilizers that emit less nitrous oxide. But at a fundamental level, climate businesses are almost always selling the power to control light and heat; mechanical work to replace or augment physical labor; or transportation for people or goods. Most of the richest men in history (Edison, Rockefeller, Westinghouse, Carnegie, Vanderbilt, Ford, Musk, etc.) sold people the power to control their environment: light when the sun wasn’t out, steaming tea or coffee on a chilly morning and icy Coca-Cola on a hot afternoon, warm air in winter and cool air in summer, machines that do the dishes and laundry, and the ability to go almost anywhere you wanted without physical effort or delay.

I am excited by the progress that many entrepreneurs are making, and I’m glad that there is a robust venture capital infrastructure to get them going. At the same time, I worry that the wisdom of the orchard is missing. Ultimately, our big emissions gains will come from machines that steadily produce power, provide light, cool or warm buildings, and move people from place to place for decades. We should be building this infrastructure with high reliability, limited maintenance needs, and the ability to recover quickly. Our failure to consider quality, maintenance, and repair is a deep cultural problem that I’ve written about before, but since climate businesses are often selling new technologies with elaborate, long-term contracts, it is even more important for them, like planters of an orchard, to think ahead about risks and stresses that assets will face even after the people who install them have moved on. Unfortunately, “impact” and “cleantech” investors rarely want to own boring, reliable things for a long period of time. They tend to concentrate their climate dollars in venture capital funds that aim to cash out in six to seven years—barely enough time for a new tree to produce its first fruit.

Bad planning leads to bad vibes and bad balance sheets

Using past ranges of weather when choosing the design and materials of a capital investment is irresponsible, but it is common and its consequences are costly. The City of Gloucester seems to have no recourse for the failure of those local windmills. In nearby Ipswich, where two more windmills stand (one working, one broken), the company that owns the windmills has offered to sell the broken one to the town for $1. The town would then need to spend an estimated $300,000 to have it taken down. There is an urgent need for climate businesses to figure out the risks that their assets are going to face so that their customers don’t wind up with buyer’s remorse. More examples might help.

A heat pump that is operating at maximum capacity many more hours than planned because the weather is more severe than in the past depreciates faster, undermining the promise that it was a money-saving investment. A “green certified” building that floods can lose value very quickly. A solar farm hit by unprecedented hail turns in a matter of minutes from an asset to a liability. Transmission lines operating in higher temperatures than they were designed for sag, have more friction, lose energy during transmission, and overheat. As we have recently learned, hot wires can ignite feathers on birds (for whom the wires are, like trees, part of the natural landscape) and start forest fires. These are not hypothetical examples.

I am worried about a near future littered with green infrastructure that has turned brown due to insufficient planning, maintenance, or insurance. That would be a terrible outcome both environmentally and politically. Try selling a second or third round of products to customers who were financially burned by cool new technology the first time around.

How can climate businesses avoid that outcome? If they start incorporating climate data into their products, services, financing plans, warranties, insurance, and messaging, they will probably encounter some higher costs and have to deal with uncertainties. It will be a hassle, and that hassle is a barrier. My Probable Futures colleagues and I have been told on several occasions, “You’re right, but our message to customers is simply, ‘It’s cheap and easy.’ Adding any discussion of climate change would make things more difficult.”

It probably is more work, but I also suspect that they are misjudging the difficulty. For climate businesses, talking about climate change is talking about greenhouse gases and regulations, which easily bleed into politics and beliefs. In contrast, my team and I also have a lot of experience talking about changing weather with people and are almost always well received. “We want your new heat pump to be prepared for a future that is likely to be hotter” is unlikely to come across as preachy. It is being diligent, thoughtful, and caring.

When people do start to focus on reliability and adaptability in the face of a changing climate, they often discover the value of shared information and modest, often even “boring” technologies like nails, gutters, text messages, databases, switches, and under-used sewers. They also find that “solutions” are more like trial and error processes rather than silver bullets. Let’s go back to the orchards.

Expensive olives, experimental papayas, and adaptive apples

In Gloucester there’s a store called Pastaio whose proprietor makes delicious pasta and sells excellent imported Italian products. Each fall she goes to Italy to participate in some kind of harvest, usually at a vineyard or an orchard. This year she was planning to go to Sicily to help a farmer there whose olive oil is particularly fabulous. By early August the trip was canceled, however, as the farmer told her he was going to lose at least 75% of his fruit to heat and drought. In Greece and Spain, farmers last year lost about half of their harvest. 2024 hasn’t been better.

The European agricultural-commercial-political system has declared that olive oil has more value than just market prices. It is a cultural heritage. So olive farmers are supported with subsidies and consulting programs. More than a decade ago, olive farmers were encouraged to adapt before climate change was a big problem. A recent article in The Christian Science Monitor quoted a cooperative leader in Greece: “The philosophy was to look at how olive tree cultivation adapts to climate change. It was the first time that we heard of the expression ‘climate change.’ We had not yet seen any consequences related to climate change. The consequences only started to be seen and felt here in 2016.” Michael Antonopoulos, president of the Agricultural Cooperative of Kalamata, added, “We are collecting olives much earlier than ever before…I think we will see less and less olive trees not only in our region, but all the Mediterranean, because the Africa heat line is moving forward to Europe.”

What I find amazing about that last quote is that Antonopoulos is absolutely correct. He understands the problem. The mountains in southern Europe mostly run east-west. This means that when heat surges north from the equator, it is trapped over Spain, Italy, Greece, and Turkey. As a result, those places are warming faster than most of the rest of the world. When I first saw maps of drought in Africa and Europe, I asked a scientist, “What’s happening in Spain, Italy, and Greece?” He replied, “The Sahara is crossing the Mediterranean.”

Here’s an image from an academic paper about climate change and olive production that shows where olives are grown:

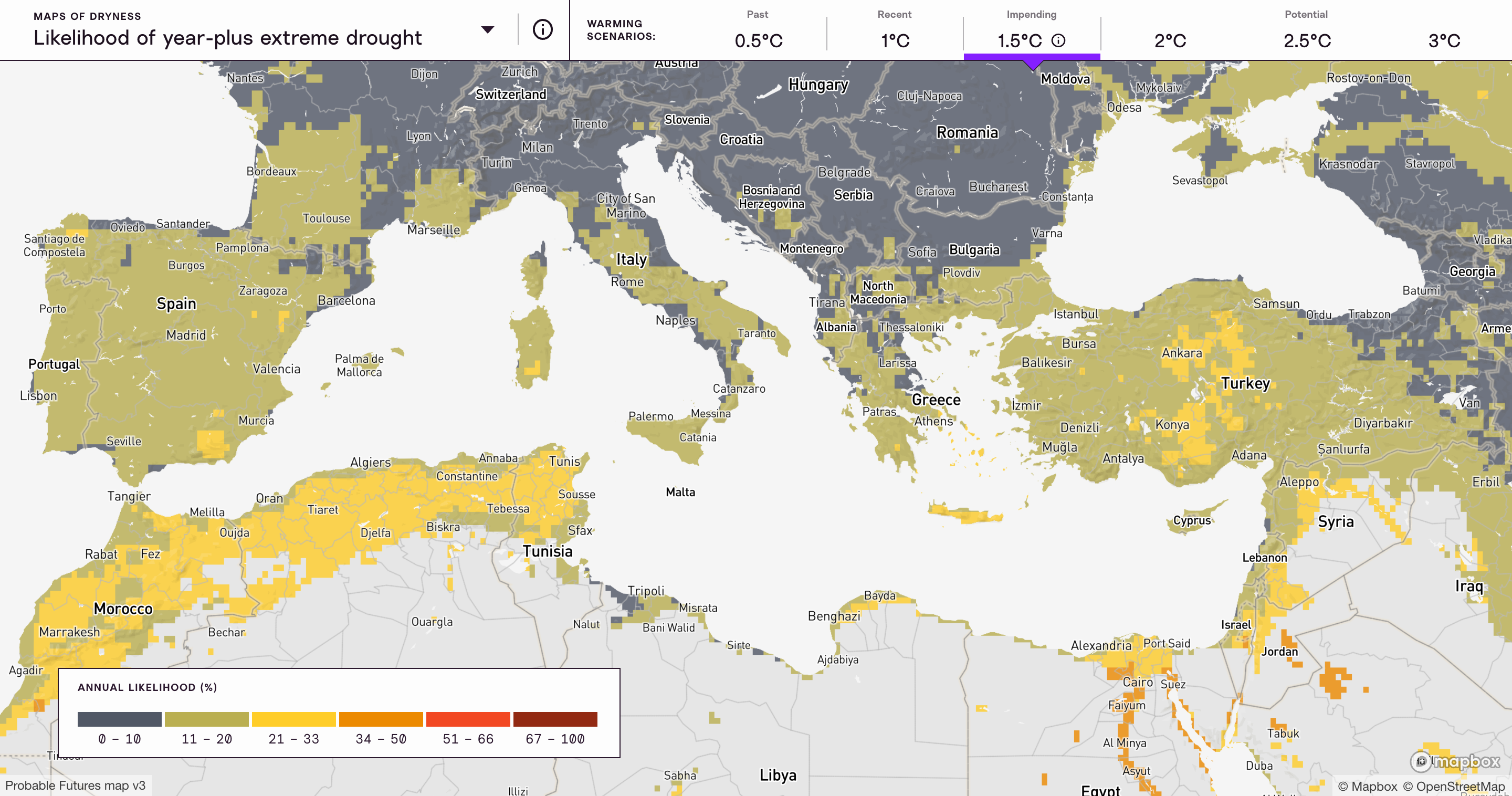

Here’s a map from Probable Futures of the probability of an extreme 12-month-long drought in the current 1.5°C climate. The pea green color indicates that a drought that might occur once in a generation should now be expected every five to 10 years. In the bright yellow regions, what used to be rare is as common as elections:

Here’s a graph of commodity olive oil prices in Europe from January 2012 to July 2024. After a decade of prices between €180 and €400 per 100 kg in the commodity market, prices for olive oil in the past couple of years have averaged €750.

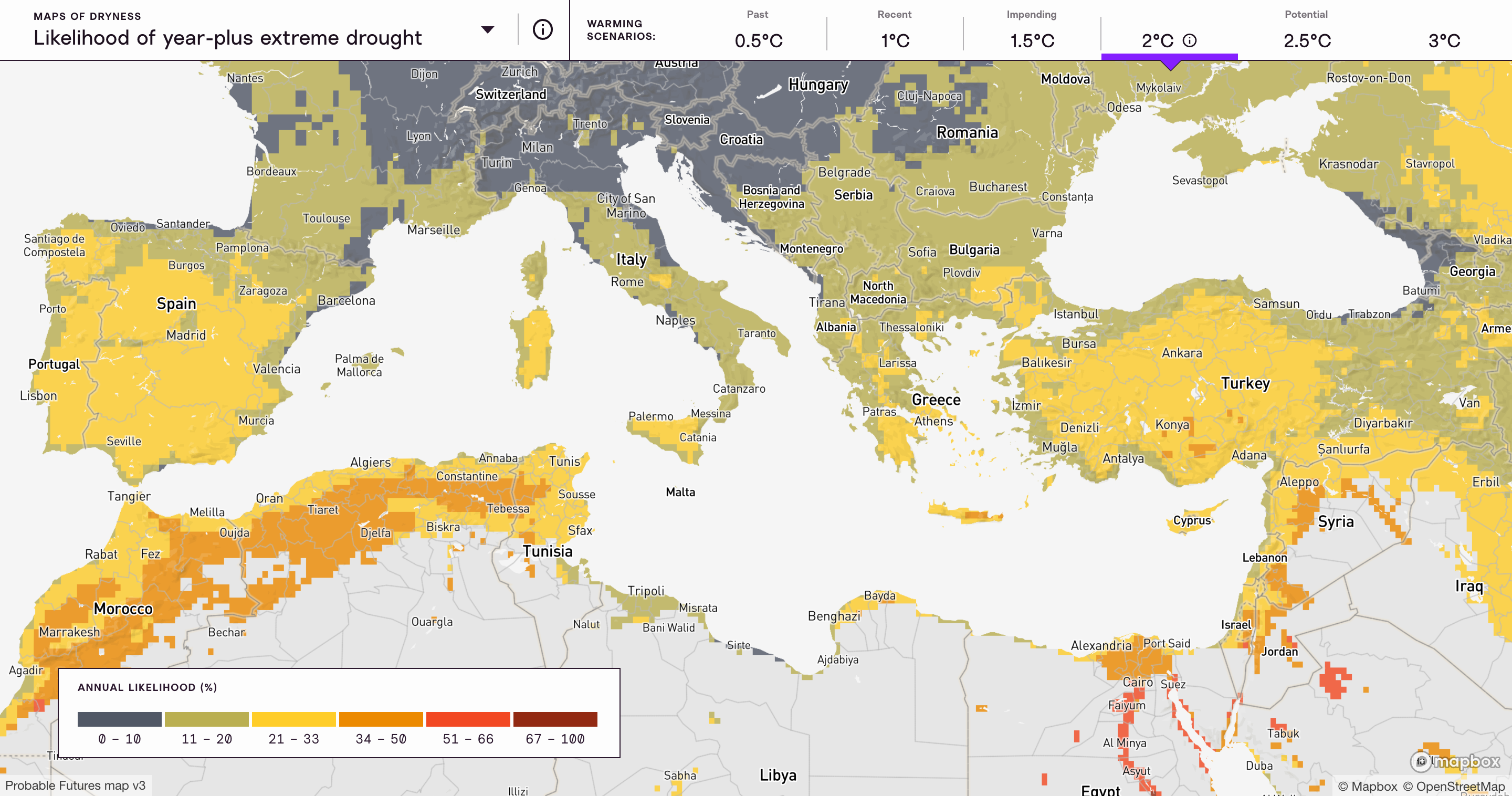

Farmers are harvesting earlier, changing their pruning techniques for both trees and roots so that olive trees have access to water further down and lose less water on top. Some are experimenting with new kinds of olives. I am hopeful that there are ways to help olive trees and olive farmers adapt. But the future likely has far fewer olives in traditional places. Here’s a map of extreme drought at 2.0°C of warming, a level that anyone planting a tree today should consider likely:

In Sicily, some farmers have accepted that they can no longer grow the olives and lemons they were known for. Some are asking, “What would grow in the climate we have now?”

In National Geographic, I read about a Sicilian man named Francesco Verri who is encouraging local farmers to experiment with exotic fruits that could grow in Sicily’s changed climate. He hopes it could be a good business and raise awareness about climate change. He is working with a local chef named Giuseppe Saitta:

Saitta is pushing the boundaries of culinary experimentation by using exotic fruits as key ingredients in traditional dishes. In a recent creation, he prepared a ratatouille using locally grown papaya and macadamia nuts sourced from nearby farmers. [As Saitta says], “The challenge is to preserve the essence of Sicilian cuisine while embracing new ingredients that our changing climate forces upon us.”

I found it to be a good reminder that, to paraphrase Wendell Berry, “agriculture is culture.”

In late August, it was clear that New England’s peach season was coming to an end. Hoping to catch the last few, we drove to Russell Orchards in Ipswich. We mostly knew Russell’s for apples and cider, but we were glad to see that they had fresh peaches from their own trees. The peaches looked too big to be good, though, so we grabbed only a few. Wanting more fruit, I looked around to see if they had any apples. I spotted a handwritten sign above a bin of medium-sized green apples: “Brand-new Pristine apple: bred for July harvest!” Lisa didn’t want to get them. A July apple? Wasn’t that accepting the end of summer prematurely? I understood the sentiment and wasn’t really hungry for apples, but in the spirit of adaptation, I bought a few.

We paid, went out to the dusty parking lot, and tried a peach. It was delicious. Lisa immediately turned around and went back inside to buy more. I waited until we got home to try the Pristine. I bit into it while I looked up the fruit’s history online. It turns out the variety was developed by a team of agricultural experts from Midwestern universities.

Purdue University publishes a wonky newsletter called Facts for Fancy Fruit. A July 2017 edition of the letter describes the Pristine as “very attractive with a clean finish. For such an early apple, it has very good eating quality.” I agreed. In fact, it didn’t even need the “for such an early apple” disclaimer. It was delicious. A crisp apple on a hot August day felt a little strange, but it also felt right. We have to adapt. The last line of the newsletter reads: “For direct marketers, Pristine may be a very good way to kick off the apple season, or to transition from peaches into apples.”

Tougher nails, interesting curbs, clean drains, and dry cars

By now you probably share my concern that if we leave farmers at the mercy of both climate and market forces, most will choose to stop trying to grow tree fruits and nuts. But you also may be thinking, “I am not a farmer, agricultural expert, or government official.” Let me explain how building and maintaining houses and neighborhoods is like planting and tending to orchards. Nails are a good place to start.

Just as planting depends on seeds, building depends on nails. And just as choosing more appropriate, hardier seeds leads to healthier, more fruitful orchards, choosing better nails can lead to sturdier, longer-lasting buildings. You may not be aware, but over the past 20 years there has been a flurry of innovation to make nails and fasteners that hold onto shingles and entire roofs in a tropical storm or tornado. On the left is a conventional roofing nail. On the right is what’s called a ring-shank roofing nail. It’s longer and has ridges that make it very hard to pull out. I doubt anyone made a vast fortune on these nails, but they have undoubtedly saved buckets of money for homeowners and insurers.

Similarly, slight modifications to gutters, downspouts, and curbs can decrease the chances of flooding in individual buildings and whole neighborhoods. New York City’s climate has changed enough for it to now be classified as “humid, subtropical” by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. It is now a prime location for sudden, heavy rainstorms called “cloudbursts.” An excellent local government presentation (which I highly recommend) explaining cloudburst management shows how different curb designs can guide water from a street that is starting to flood into nearby absorbent areas. The same document vividly demonstrates how to avoid clogged storm sewers:

For every piece of infrastructure, there are examples like this. It may not be sexy and the returns may be hard to see, but it’s the kind of work that has held institutions and communities together in the past and will be even more essential as climate change adds further instability. It’s exciting to see people grasp this and put it to work. I had that experience a couple of weeks ago.

Probable Futures is now a core part of the executive education program at Harvard Business School. Leaders from companies around the world who come to learn management techniques and meet other leaders now get a climate risk primer, learn how to use our tools, and do casework we helped design. In class, I give a short lecture after which Professor Mike Toffel asks the students to share a physical climate risk that their business is facing. Mike explains that it could be with their suppliers or customers or inside their operations. We did this for the first time last year, and the response was great. This time, every one of these executives had a story they wanted to talk about. I learned about pet health (dogs don’t want to eat or go outside when it’s hot), shipbuilding (drought in Panama made the Panama Canal inoperable, which led to more ships at sea for longer, which led to more demand for ships), disastrously ruined date farms, and all kinds of other business challenges. One example stuck with me.

An executive from a new Chinese EV manufacturer explained that flooding is a threat to their business. If an EV is submerged, the battery will be damaged, causing a warranty claim. He held up his phone and explained that his company had developed a flood monitoring and alert system that notified drivers of their cars of flooded roads and provided directions to higher ground and safe parking. He said it helped reduce repair costs and increased customer satisfaction. I thought it was a great example of how markets can contribute to adaptation.

The main event and the underground scene

I am looking forward to being in New York for Climate Week, not just because the storm sewers will be clean. I was invited to the NEST Climate Campus, the open-to-the-public counterpart to the invite-only Climate Group event, to offer a keynote about adaptation. I will be glad to have a big audience for this work (please come if you are in town!), but am even more encouraged by the handful of smaller, adaptation-focused events being held around the city—in coffee shops, coworking spaces, and generic office buildings—hosted by journalists, construction companies, designers, and consultants. Our friends at Aboard are hosting one for adaptation data nerds!

Each of these events sounds interesting. Their small number, broad descriptions, and distance from the main stages make it clear that the climate business and climate philanthropy communities have barely begun to figure out how to engage with adaptation. They want proof, metrics, and credit. While decarbonization lets funders point to units like MWh and gigatons of CO2, climate literacy, risk awareness, and preparation—the ingredients in successful adaptation—all silently reduce future losses and suffering. How do you count the EV that avoids the flood or the roof that doesn’t blow off? In these days, when many people believe that everything needs to be measured to matter, reducing risk feels risky.

Thankfully, organizations and individuals who have long been comfortable with risk are finding ways forward. This is why the event I’m most looking forward to is a dinner cohosted by Probable Futures and a brand-new entity called The Resiliency Company (TRC). TRC was created by leaders of the nonprofit giving platform Network for Good, which was built to help facilitate and expedite effective charitable giving after catastrophe. While at Network for Good, their experience with natural disasters showed them the need for organizations like TRC and new approaches to adapt to climate change. They have big institutional plans that sound great, but right now I’m excited about a meal.

The dinner is the day after the September equinox. In attendance will be leaders of a new adaptation advisory company, people inside and on the fringes of the insurance industry, risk-aware management consultants, journalists who have decided to make adaptation their new area of focus, a leader of an adaptation investment, and a few others. Our group may seem nerdy, and adaptation may feel countercultural, but this is how jazz, disco, punk rock, new wave, and hip-hop all got started: A small group of people who are excited about something new, who are convinced the rest of the world is missing out, get together in a room in New York to create a scene, to start a movement, to make something happen. It can be fun and cool. I’m confident that before long, other people will be throwing their own adaptation parties. You could even host one in your neighborhood!

As the equinox passes, we all shift into a new season. It’s beyond our control. We adjust what we wear, what we do, and what we eat. Our bodies feel the changes and react. We adapt. The seasons aren’t the same as they used to be, but they are still familiar. Lattof Farmstand has no walls or heat, so it will soon close for six months, but I’m no longer hungry for peaches anyhow. Thankfully, there are many places to buy apples, pears, and other tasty things that I’m excited to eat. I hope there are things you’re looking forward to in the coming months as well. I will send another letter in three months at the December solstice.

Onward,

Spencer