Greetings on the first equinox of 2022. Today every place on Earth receives an equal 12 hours of sunlight. Tomorrow half of the planet will get less and the other half more. It’s an apt moment to write about what we share and what separates us, two of the threads that run throughout Probable Futures and have animated my interests for over 30 years.

Family ties

I spent my youth going back and forth between places that were prosperous and places that were desperate. As a boy, I lived in Ann Arbor, a city of 100,000 people built around the University of Michigan, which both of my parents attended. My mother was from Detroit, my father from a small town called Bad Axe. My memories of the 1970s and early ’80s are a collage of contrasts: colorful, optimistic energy in Ann Arbor, tragic, violent decay in Detroit, and slow, slipping obsolescence in Bad Axe.

By the time I left home at 18, I was obsessed with understanding why some places thrived while others collapsed. As I tried to figure out the world, an argument was raging around me about how society should be organized, and what constituted constructive and rewarding work. I read books, took classes, lived in Germany, worked in banks in Chicago and Russia, got degrees, and spent a decade going back and forth between Boston and China. Still, the clearest distillation of the argument was set in my mind by a random episode of a TV show called Family Ties that aired in 1986.

In the show, Michael J. Fox stars as Alex P. Keaton, a teenager who, to the chagrin of his bourgeois hippie parents, was a free-market zealot. In one particular episode, Alex is alarmed to find his three-year-old brother wearing a badge from preschool, proudly stating, “I know how to share.” Alex takes matters into his own hands and fashions a new badge for his brother to wear the following day that boasts: “I know what’s mine.” The battle within the fictional Keaton household was between those who believed sharing was the key to a harmonious society and those who believed individual action and competition would lead to a better, richer one.

I’ve excavated this obscure TV history because the futures of both civilization and abundant nature are at stake, and failing to understand the relationship between sharing and markets is a grave threat. Even if you think stock markets are the best proxies for societal health—and Milton Friedman, Ronald Reagan (who reportedly said that Family Ties was his favorite show), Margaret Thatcher, and Ayn Rand are your heroes—you should be promoting shared information and working to strengthen shared institutions.

A deluge of for-profit climate analytics

We started building Probable Futures a little over two years ago and are releasing the second volume of the platform today (more about that below). One of our main motivations has been the threat of climate data being owned instead of shared. It seemed likely that rich people and corporations would have access to climate data for a fee, while everyone else would have to rely on journalists and occasional government reports to get a sense of what was coming. Unfortunately, that world has already arrived.

There are now many companies that have raised tens of millions of dollars to sell “cutting-edge climate analytics” to clients from hedge funds to real estate investors to multinational corporations. These companies offer insight about the probability of physical risks to specific assets in specific locations given different climate scenarios. Most of them are focused on flooding and storm risks, with some also offering fire risk assessments and heat wave information. It’s a reasonable business proposition. What could be wrong with that?

Smooth sailing

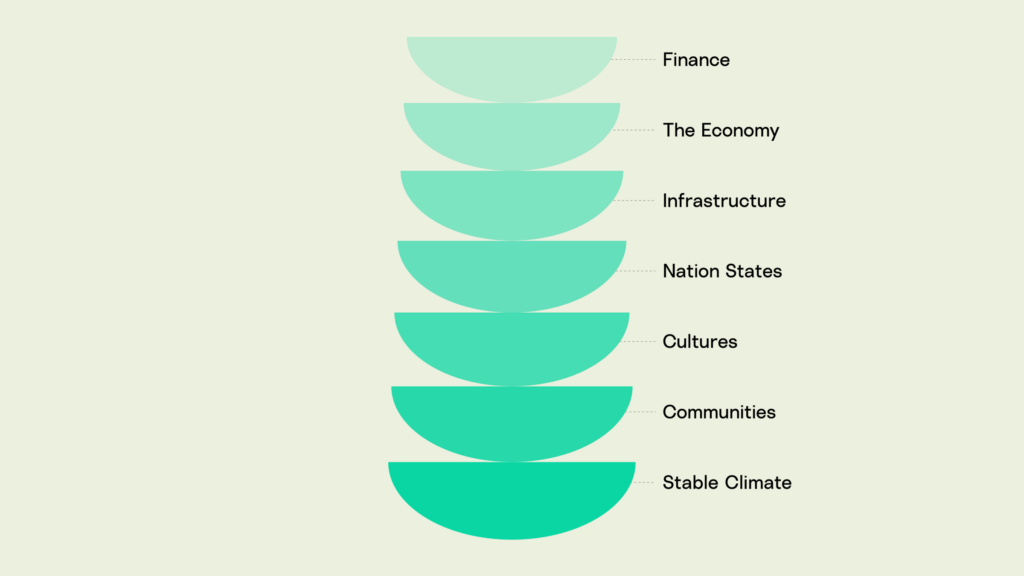

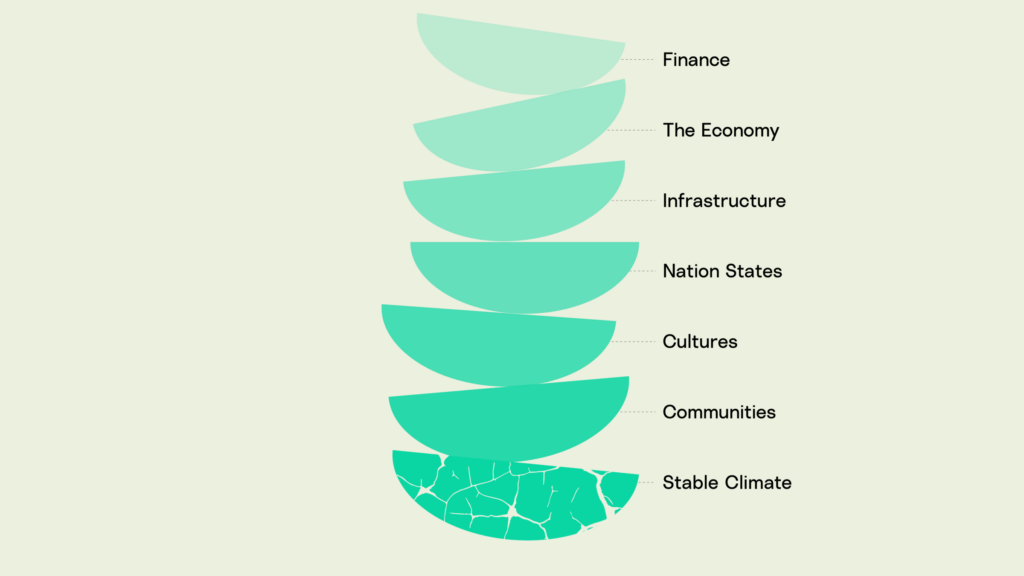

The “free market” concept didn’t even arise until the late nineteenth century. Only after groups of people had settled, formed communities, developed local cultures, languages, norms, and traditions, created nation states, and begun to industrialize did the idea even make sense.

In a country with clear laws, a stable government, lots of allies, international trading agreements, and no existential worries, markets are amazing. Margaret Thatcher asserted that a market economy was the best, right, and only system that works. Her slogan was TINA: “There is no alternative.” In the peaceful 1990s, Bill Clinton’s presidential campaign message was simply, “It’s the economy, stupid.”

At their essence, markets are information systems. The compelling argument for them is that having lots of private individuals observe the world and make decisions about what to buy and sell, and at what prices, leads to more of what people want at lower costs with minimal waste. This is the ideal toward which Friedrich von Hayek, Milton Friedman, and their followers wanted to direct twentieth-century people who were tempted by communism or big government. A central planner could not possibly collect, process, or distribute information as accurately or efficiently as a decentralized market. Their vision was an unplanned, competitive, free, and fair society in which a rising tide lifts all boats.

This vision was compelling, and my experience working in Russia in the early 1990s and China in the early 2000s allowed me to see the poverty, waste, and environmental damage that communist plans often left in their wake as well as the ways markets could liberate people. But I also came to understand how many things had to be going right for “free market” politics to make sense. While markets did amazingly well getting the small things right, they often had no good answer for the big things in life.

Precarious vessels

Even under the most favorable external circumstances, markets can fail to produce broad prosperity. For example, when some people know something important and others don’t (“asymmetric information”), outcomes become distorted. Those with the information gain outsized profits, and those without it wind up paying a lot for little or no benefit. A person who shares information helps markets work well. A person who hoards private information wants to “beat the market.” An advantage that produces sustained profits is sometimes called a “moat.”

A few years ago, on a gray day, I was sitting in my 25th-floor office in one of the world’s largest investment firms, where I was paid handsomely to generate private information that would help the firm’s clients beat the market. I had been piecing together the history of climate and connecting it with the history of economies to figure out what effect climate change might have on finance. I turned away from the notes and books on my desk, looked out across Boston Harbor, and let the truth wash over me: Every thing, person, and place that I cared about, every aspect of culture, work, business, and government, indeed every facet of civilization existed because of a stable climate:

I had started researching climate change partly because I thought there might be an opportunity to discover insight that others didn’t have. Once I had that insight, however, it became obvious that for civilization to have a chance, everyone needed to have it.

I came to see the glass office buildings that house modern finance as precarious vessels hovering so self-assuredly above the human and natural world that their occupants cannot see the powerful, complex, elaborate forces that prop them up. As people speculate in financial markets, buy and sell in the economy, and argue about infrastructure in halls of government, few seem to understand that the foundation below them is both shifting and cracking. Until they see how fundamental the bottom is, the top of this tower will only grow more precarious. Stabilizing the climate is the only way to truly reduce risk.

Drawbridges and lifeboats

In the past year, I have seen a number of presentations by climate companies and their clients at finance and business conferences. They all told stories like this:

In 2019, a climate-aware private investment fund in a suddenly fire-prone country decided to add a new large-scale residential building to their portfolio with the objective of securing at least 30 years of steady income. Their team identified a piece of property directly on Boston Harbor in the lower-income/gentrifying neighborhood of East Boston. They hired a climate analytics company to assess the risks of flooding in the location. The climate analytics company produced maps that showed the probability, extent, and depth of flooding of their proposed location and of the surrounding neighborhood in 2021 and in different prospective scenarios of warming and timing.The upshot was the following:

- The proposed location had already flooded in storms, as had parts of the surrounding neighborhood.

- The depth, extent, and frequency of flooding will increase with time and rising temperatures.

- During floods, there will be no access to the location.

- The surrounding neighborhood is unprepared and extremely vulnerable.

Armed with this insight, the fund bought the property. They then hired architects and engineers to design a “climate-prepared building.” The resulting “resilient” structure has:

- A drawbridge-like wall to keep the below-ground parking lot from becoming an aquarium during floods.

- A vacant first floor so that when floodwaters breach the barriers, nothing will be damaged.

The person who presented this project was proud of their firm’s holistic approach. Indeed, the company had done work I had never seen elsewhere, including laying out what it thought would happen to society under different warming scenarios. 3°C: Polarization: National self-interest prioritizes local adaptation over multilateral action. 4°C: Resignation: Resources and efforts solely focused on adaptation and survival. And yet, I sat there looking at the slides thinking, “Was there really nowhere else to build out of harm’s way?” “What will happen when this is the only safe building in the neighborhood?” “Will this building have a refugee policy for taking in desperate neighbors?” “Did the company share the results of its research with the city, the local councilwoman, the neighbors?” “Does the building have its own backup generators? Lifeboats? Guns?”

Many of these firms boast about being able to assess risk for a single specific building or asset. Extreme “granularity” is seen as more valuable than analysis at a wider scale. This is exactly the kind of application that we feared when we started Probable Futures because it both assumes and encourages a kind of “everyone has to fend for themselves” thinking. Amitav Ghosh has referred to this as “armed lifeboat politics.” In truth, no one can actually fend for themselves for long in a crisis, and avoiding crises—the strategy with the highest returns—can only be done in community.

Risk pooling

When I talk with people about climate change and finance, most of them immediately bring up insurance. “Insurance companies must be all over this” and “insurance companies must be screwed” are two common theories. I tell them that I am not worried about insurance companies. I am worried about insurance markets disappearing. I am even more worried about the fact that there is no insurance policy for societal catastrophe.

The majority of insurance is a form of “risk pooling.” Long before there were insurance companies, people recognized risks and figured out ways to lessen their impact by sharing the risk. The basic idea was that a bad thing might happen to a member of a group, but it was impossible to know in advance whether it would happen or to whom. If members of a large group divided their assets, all wouldn’t be lost in a calamity. Insurance was a financial innovation: If people made monetary contributions to a shared pool, then each could be entitled to compensation if a bad thing happened to them.

One classic example of insurance markets leading to growth and shared prosperity is maritime insurance in seventeenth-century London. All shipping vessels carried goods of known quantity and price, and a few would sink or be overtaken by pirates. In the late 1600s, Edward Lloyd ran a London coffee house where ship owners would drink, talk, invest in one another’s ventures, and find ways to share risks. This coffee shop led to the creation of one of the more remarkable and unorthodox organizations in the world, Lloyd’s of London, a marketplace for insurance and reinsurance. Lloyd’s isn’t a company but rather a corporate body governed by rules established by the British House of Parliament. It has a motto: Fidentia, Latin for confidence.

The availability of good information and the formalization and growth of the insurance market made shipping less risky and cheaper, both of which led to an increase in supply of shipping, which lowered prices of things like coffee, which helped make the drink accessible to people who didn’t own ships (which made modern capitalism, including working the night shift, possible).

Here is a list of conditions necessary for a healthy insurance market. See if any are threatened by climate change:

- Losses should be predictably unpredictable. In other words, the overall pool must have highly predictable loss characteristics, but it must be impossible to say precisely which member of a pool will suffer a loss.

- Losses are uncorrelated. Put differently, a loss by one member of a pool is independent of losses by others, so losses won’t happen in bunches.

- Losses are small relative to the size of the insurer. That is, no single loss event or set of losses in a short period of time can threaten to wipe out the pool.

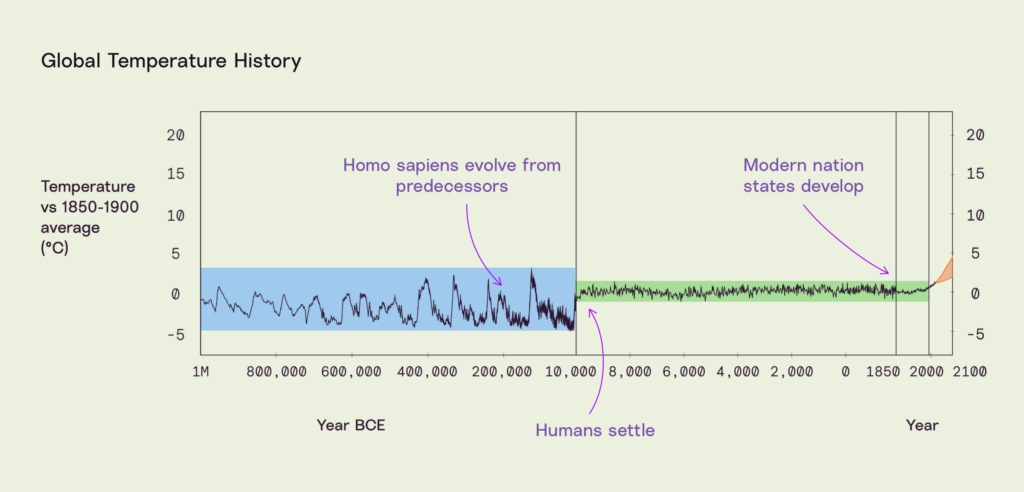

For 10,000 years, we enjoyed a stable climate. It wasn’t without fires, storms, floods, or droughts, but the frequency of events was consistent. In statistics, this phenomenon is called “stationarity.” Stationarity is great for insurance. For example, if you have 200 years worth of data, a storm that appears twice in that time might be called a “1-in-100-year storm.” That doesn’t mean the storm will come around every 100 years, but that in a given year, such a storm has a 1% probability. A 1% loss frequency is desirable in insurance markets, as losses are small relative to the pool. Indeed, the 1-in-100-year flood is the most common standard for insurance, regulation, and engineering.

Fluid forecasts

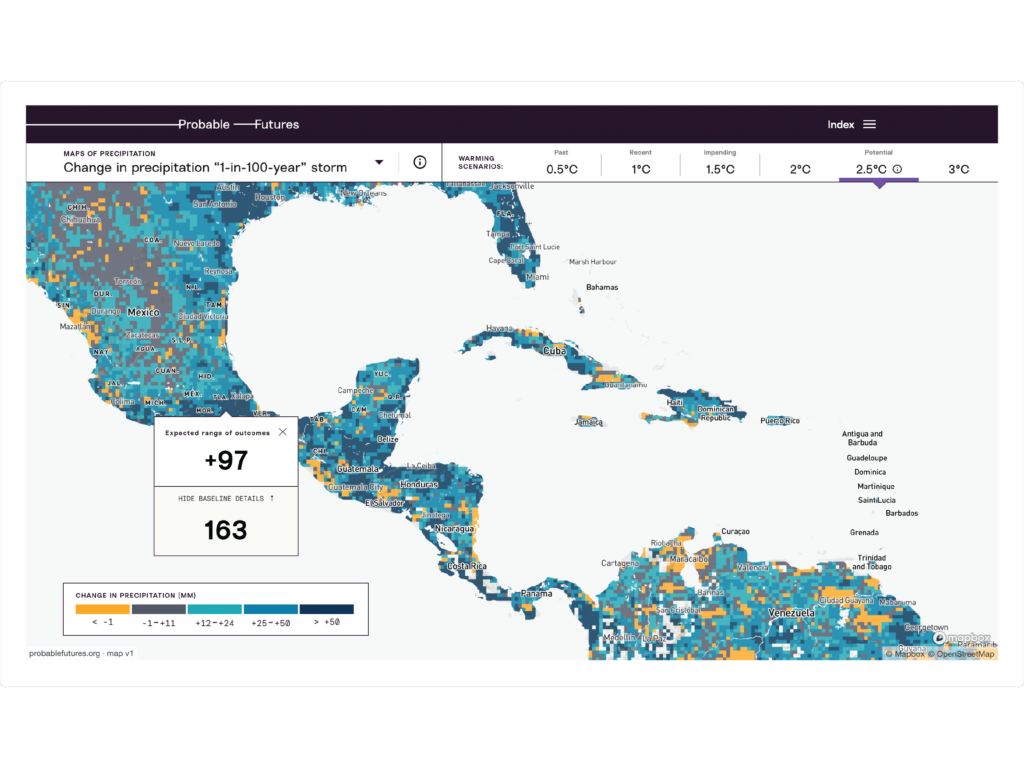

By now you might have noticed (or grown tired of) the water puns and metaphors in this letter. Water is the topic of the new volume of Probable Futures. I am excited about the ways our team has found to explain changes in the water system brought on by climate change and the maps of precipitation, including how 1-in-100-year events are likely to change as the atmosphere warms.

Here is a snapshot from a map that shows how much rain will fall in a 1-in-100-year storm at different warming levels. I highlighted a spot in Puebla that is roughly the same distance from Mexico City as my childhood home was from Detroit. In this location, the 1-in-100-year storm in the late twentieth century dropped 163mm (6.4in) of rain in one day. If the atmosphere warms to 2.5°C—which is likely in the coming decades if we don’t radically reduce carbon emissions now—a 1-in-100-year storm could drop an additional 97mm (3.8in) of rain.

I strongly encourage you to check out the volume. The earth’s water system is fascinating and beautiful, and, like most aspects of climate change, it is intuitive. You don’t need machine learning or a supercomputer to understand the main issues. Warmer air melts more water, evaporates more water, and holds more water. This is why warmer air can be more humid (as explored in wet-bulb temperature maps in the Heat volume) and can drop more rain than cool air can. Warmer air also pulls more moisture from the land, worsening droughts (which our third volume will explore in detail).

On average, the atmosphere is getting wetter, and extreme precipitation is becoming more extreme. What was a 1-in-100-year storm in the past now has a higher probability in most places. But how much higher? It’s impossible to know precisely because as greenhouse gases trap more heat, an already complex system becomes more complex. The range of outcomes and their probabilities are shifting.

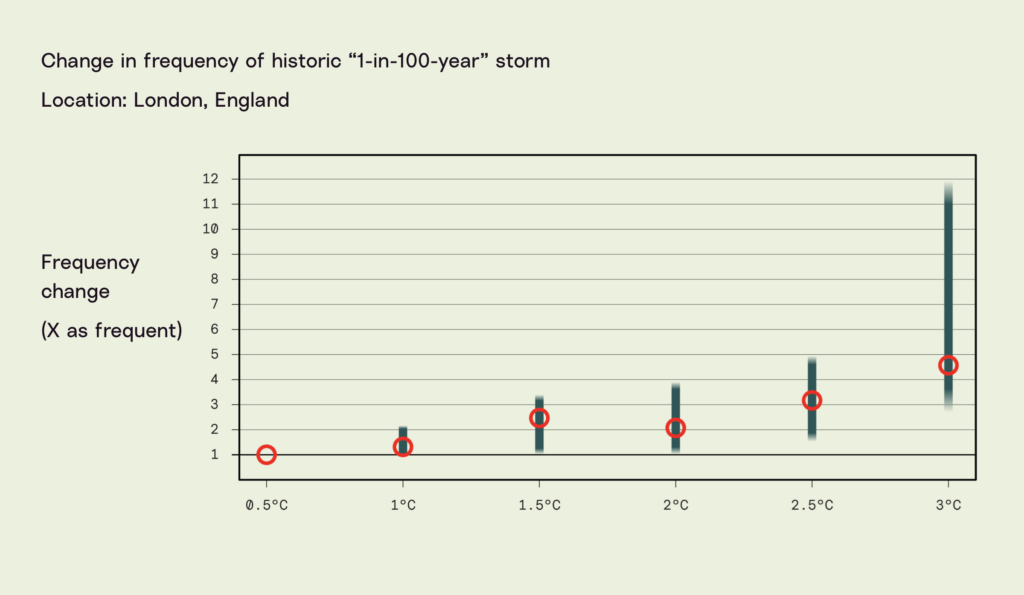

Consider London, a place whose mild weather helped it thrive. We knew what the 1-in-100-year rainstorm was, but does that same storm still have a 1% chance in a given year now that the atmosphere has warmed more than 1°C? How will that likelihood change as the atmosphere warms further? The chart below shows estimates based on results from the climate models behind Probable Futures maps. Circles indicate the median of the model estimates, while the bars stretch from the 25th percentile to the 75th.

The historical 1-in-100-year storm grows more likely as the atmosphere warms, but precisely how much more likely becomes more uncertain as the climate gets further from the stability we enjoyed for thousands of years. The bar at 3°C shows that such a storm might be 3 times as likely as it was when the atmosphere had only warmed 0.5°C, but it also might be more than 11 times as likely.

The transition from a stationary, predictable climate to one filled with uncertainty is likely to be painful and costly. Increased “climate intelligence” may lead to smaller insurance markets for at least two reasons: In many cases, perils will be too frequent, too large, or too correlated to meet the criteria for insurance, while in others, insurers and their potential customers won’t know how to assess risks or price them at all. To appease voters, some governments are already trying to compel insurers to offer coverage in places with rising risks, while others are stepping in to offer insurance where private markets have dried up. These market distortions are dangerous, especially if they distract people from the real work of preparing.

A rising tide floods all moats

When I was first coming to understand the scope and speed of climate change, I sought out insurance experts. Two conversations from that time are seared in my mind.

The first was with a climate expert at a Swiss reinsurance company. Reinsurers insure insurers. That’s an odd-looking sentence, but it’s an important one: Even insurance companies buy insurance. Some of the smartest climate people I have met work in reinsurance. I was in my 25th-floor office, watching giant cranes assemble new buildings, as this scientist taught me about the limits of insurance. “The first time a building floods, it’s an insurance problem,” he said. “The second time, it also might be an insurance problem.” He paused, then delivered his punchline: “The third time it becomes an equity and debt problem.”

If a building has not flooded, it’s easy to get flood insurance; when a flood happens, the insurance company has to pay. The next time it floods, the insurance company will be less surprised and will probably have charged a higher rate to the customer, so there will be smaller losses for the insurer. By the third flood, however, the major loss won’t be insurable: The location will start losing market value as potential buyers look to other locations that don’t flood regularly. That’s a problem for the owners and the lenders.

I came to understand something that I hadn’t thought about before: Property insurance only protects the structure, not the land value. The helpful expert told me that it’s virtually impossible to have an insurance loss of more than 10% of the value of a big building. “Insurance pays to replace windows and carpets and to repaint,” he said. “That’s not the main source of value in a big building. There is no insurance for a location going from desirable to undesirable.” Insurance doesn’t protect against collapse.

Not long after my crash course in reinsurance, I was in an intimate meeting with the CEO of a leading insurance company. The conversation was wide-ranging and good-spirited. At one point, a colleague asked the CEO, “What did you learn from 2008?” The CEO thought for a minute and said, “That when a tidal wave comes in, everyone gets washed away.”

In 2008 and 2009, many insurance companies either went bust or applied for government bailouts. The CEO was saying that the losses created by the global financial crisis were too large for any insurer, so they all went bust. But what happened to insurers in 2008 and 2009? Were there lots of storms or car accidents at the same time? Did a plague unexpectedly kill millions of people, prompting extraordinary payouts? No. The crisis was not among the members of the pool. It was in the pools themselves. You see, insurance companies take all of those payments and invest them in asset markets. If they can earn a nice return on the pool, they can gain profits above and beyond the returns gained from skill and luck in underwriting.

The risk that insurance companies will be too aggressive in their investments is well known, so they are regulated. The primary form of regulation is a set of limitations on what assets insurance companies can buy with their pool. They are generally restricted to securities that are highly rated (e.g., AAA, AA, A) by ratings agencies like S&P and Moody’s. In 2008–9 the “tidal wave” that wrecked insurance company balance sheets was caused by the ratings agencies systematically underestimating the riskiness of many bonds, partly because they didn’t understand the risks, and partly because they were paid to downplay them by the issuers of the bonds.

Ratings agencies are strange creatures. They are supposed to be neutral referees or judges that publish shared standards to help markets work well. Unlike Lloyd’s, however, they aren’t overseen by a government or a set of rules. They are aggressive for-profit companies whose customers (the issuers) want the agencies to give overly optimistic assessments of risk so that they can sell their bonds at lower prices to insurance companies, pension funds, and the like. The ratings agencies generally bear no responsibility for mistakes. Indeed, despite being central to the global financial crisis, they are essentially the only institutions that were not reformed afterward. I bring this up here, because ratings agencies have been the biggest buyers of “climate intelligence” firms that sell proprietary, black-box analytics. The neutral judges of risk are now selling access to private information so that their customers can establish their own competitive moats. This does not inspire “fidentia.”

Government bailouts

After the CEO said that insurance markets were unprepared for major disasters, I said something he didn’t like: “If private insurers are only prepared for minor risks, then the government is the only true insurance.” I will not detail his response, but Alex P. Keaton would have enjoyed it. Many modern business people do not like to admit that their “free markets” depend on governments, but the wisest investors I have met understand this.

Not long ago, leaders at one of the most successful investment firms in the world reached out to me with a surprising message of encouragement. They wanted me to know that they supported my work because “we see that if the climate crisis gets worse, governments will have to grow and markets will shrink.”

This is the kind of understanding we need from financial, economic, and governmental leaders: If you want to have competitive markets in the future, you need to help strengthen governments, regulators, and shared resources now. I am hopeful this can happen. One source of encouragement is the work that McKinsey has produced in the past two years, including recent work on getting to zero emissions in a fair, peaceful way. I highly recommend them (see “Links” at the end of this letter).

Do you know how to share?

Alex P. Keaton thought his brother’s “I know how to share” badge was wrong-headed. Others might look at such a badge and think it’s sweet but childish. Ask yourself, though, do you know how to share? When I first asked myself that question, I discovered that I didn’t. I knew that the stable climate we share was fragile and our society in peril, but what could I do?

Once I left the heights of finance, I started to see the webs of sharing that had propped me up without my paying attention. Things that were “outside of work” were in fact what made that work possible. Look around you and see what you share: family, friendships, neighborhoods, town and city councils, school boards, zoning committees, charities, professional associations, industry groups… make your own list. All of these shared connections need to incorporate climate change in some way, and the stronger they are, the more prepared and resilient we will be. The best assurances aren’t financial contracts but plans, connections, mindsets, cultures, and relationships.

Alison Smart, Executive Director of Probable Futures, and I discovered an opportunity to build a new shared resource and a community around it. Probable Futures isn’t a business or a government. It’s an initiative to increase the chances that the future is good. To that simple and ambitious end, we have worked to make it useful for today’s society and to help everyone imagine, shape, and prepare for healthy, resilient, joyful societies in the future. We do mean everyone, but sometimes a corporate-sounding, alliterative list can be helpful, and a final water-themed pun can’t hurt.

Probable Futures is for the Seven C’s

Citizens: All of us are citizens with civil, political, and social rights and responsibilities. Many of the readers of this letter likely worry about national and international politics and feel helpless. Preparing and adapting, however, are local and tractable. Join a local group, run for local office or help someone else to do so, or volunteer or protest in your community. Bring our platform with you to make climate conversations practical and vivid.

City and town officials: There is one set of organizations that absolutely needs help understanding the physical risks and challenges of climate change: local governments. We are hopeful that our tools and maps will help with the planning and management of local institutions and infrastructure.

Customers: A marketplace of competing climate service providers can be a great help to society if customers are knowledgeable about what they are buying. Probable Futures is already working to help reduce the information asymmetry that currently benefits the sellers and hurts the buyers. Our Science pages explain the climate models on which all climate intelligence is built, which helps companies understand what kinds of questions to ask of experts and what kinds of answers to trust. We are hopeful that, aided by global, shared, free information, markets can generate the amazing outcomes (e.g., abundant, high-quality climate services at a low cost) they are capable of.

Climate professionals: Soon enough, everyone’s job will require climate awareness, much like how “information technology” went from an esoteric interest to a necessary competency. Many companies are assigning a few people to a “sustainability” or “ESG” team, but millions of people will rapidly follow. Probable Futures can be used in professional training.

Collaborators: We will only be successful if we work together. If you see a way to work with Probable Futures or want to use our platform to do something, please reach out.

Creatives:Family Ties was a successful TV show built around a set of societal concerns. Popular comedies and dramas that lay bare our beliefs, identities, and choices are vital, but thus far almost none include climate change. Recent novels have helped readers grapple with the topic, but we need a boatload more of them. Similarly, poets can help us find language for strange new thoughts and feelings, and visual artists can help reorient the way we see ourselves and the world around us. As I discussed in a previous letter, I hope musicians can create a soundtrack for positive change.

Children: The readers of this letter are overwhelmingly adults. There is one thing that definitely is not yours or mine: the future. To the extent that it belongs to anyone, it belongs to children. I think about kids in Puebla, Ann Arbor, Detroit, Bad Axe, London, and elsewhere, and wonder if they have a sense that something isn’t right and that their futures are at risk. My colleagues and I believe that they deserve to know what’s coming and what they can do. We have worked to make our platform and tools accessible and compelling so that they could be used in classrooms—from middle school to universities. We are encouraged by the conversations we have had with educators and look forward to many more.

I want to end this letter by offering thanks. I sent my first equinox letter just after Covid-19 shut down much of the world. I am writing this one as Ukrainian volunteers try to fight off the Russian army. With so much darkness and distraction, it would be understandable if you resisted thinking about climate change. I am grateful to you for reading my letter and being part of our community. Our widening, deepening connections with people around the world inspire us to keep working on Probable Futures.

Onward,

Spencer

Links:

A recent article by collaborators from McKinsey & Company that illuminates the spending and cooperation that will be necessary to address climate change and includes links to other research.