In 1999, I was hired by an investment management firm called Wellington Management. The Asian financial crisis was ending, and the firm wanted help figuring out how to approach the region. I was finishing a Ph.D. in economics on the industrialization and urbanization of the United States, had previously worked in a diverse set of countries and contexts, and spoke mediocre Chinese. I had never been to Asia. Wellington took a chance on me, and I on them. My job title was Asia ex-Japan macroanalyst.

By population, China was by far the biggest in the region but had tiny capital markets. In the eyes of most investors, it was a small, closed country that didn’t figure into their assessment of asset values or the global economy. It was less important than Singapore. Because I had never been to Asia before, I asked for two months to travel around the region, four weeks of which I would spend in China. Deborah Allinson, my creative and far-sighted boss, suggested that I reach out to the investment banks around the region to help me set up meetings.

There were experts who could connect me with government officials and leaders of big businesses in Beijing and Shanghai, which together were home to about 23 million people. When I told them I wanted to go to places on the map that I’d never heard of but where the other 1.2 billion Chinese people lived, they were unable to help much. They had never been to such places. So, without much sense of what I would find, I started roaming and paying attention. What I saw was too big in every way to comprehend.

There was construction everywhere, as 20 million Chinese people were moving into cities in 1999 alone. Nonetheless, there were systems and order. Things were messy, but they worked. The kind of industrialization that had taken decades in the U.S. was happening in years or less in province after province. New housing was being built on an immense scale. A development with multiple towers—each 20 stories high and housing several hundred people—was commonplace. I had trouble convincing people in these places that Boston, the famous American city where I lived, had fewer than 700,000 people and no residential buildings higher than perhaps 15 stories.

After that trip, I developed a practice: Go to parts of China that weren’t well known but had millions of people. I spent six weeks a year on these journeys, and each time I went, I came back more convinced that China wasn’t a buying or selling opportunity but rather a fundamental change to the workings of the global economy, global finance, and even the biology and chemistry of the planet. I didn’t see what was controversial about my views, but people in the U.S., Europe, and even Beijing had trouble believing me. So I decided to run an experiment.

In 2001, I surveyed the chief Asia economists from several global investment banks (these are the folks quoted in the Financial Times and The Wall Street Journal about economic news). I first asked them: When will China’s economy be larger than Japan’s? Their answers all ranged from 20 to 30 years (2021 to 2031). I then asked them to forecast annual GDP growth, inflation, and currency appreciation vs. the US$ over the coming 20 years. All gave the same answers: Japan would experience zero growth in GDP and no inflation or currency appreciation, while China would average 8% GDP growth, 2–3% inflation, and 3–4% currency appreciation year after year.

At the time, Japan’s annual GDP was US$4 trillion and China’s had just reached US$1 trillion. By their numerical forecasts, Japan’s GDP would therefore still be US$4 trillion in 2021, while China’s, compounding at about 14% (8%+3%+3%), would pass Japan’s around 2010 and be about 4x larger still in 2021 or so. In other words, their answers to the two questions were at odds with each other.

When I said, “Your forecast tells me that China will pass Japan in 10 years,” each of them replied with some version of “You’re too bullish on China.” Bullishness is a finance term that combines an opinion with a feeling or even a desire. I tried to point out that I wasn’t expressing an opinion or a feeling; I was just applying the math they gave me. In one meeting, I was so perplexed that I drew a table on a notepad and showed the head of a French investment bank how his own numbers produced this outcome. “That will never happen,” he said.

China passed Japan in 2010, and in 2022, adjusted for U.S. inflation, Japan’s GDP is roughly US$4 trillion and China’s is roughly US$14 trillion. Their numerical forecasts were amazingly accurate—they just couldn’t believe them.

Knowledge and belief

“Belief” was what got me to really dig into climate change in 2012. I was still in finance but no longer working on China. I was overseeing macro research at Wellington and looking for topics that could matter a great deal but that finance people didn’t pay attention to. Climate change struck me as a good candidate, in part because people used funny language when it came up: “You believe in climate change?” or “I don’t believe in climate change” were somehow perfectly reasonable things to ask or say. This kind of binary stance, “It’s true or it’s not, and my belief precedes any inquiry,” should be taboo in finance which, at its core, is about making decisions under uncertainty. I reckoned that if people in finance were preventing themselves from even considering the issue, there was a chance I would find something useful by trying to get to the bottom of it.

I quickly discovered that climate models had been remarkably accurate in their predictions. As I got to know more earth scientists, though, I found that many of them also had trouble reconciling their disciplines’ insights projections with their beliefs about human life.

In 2018, I gave a presentation to an audience of esteemed climate scientists at the Woodwell Climate Research Center that included the following:

The northern coast of Africa, home to hundreds of millions of people, is transitioning from a Mediterranean climate to a desert; the timing and intensity of rainfall in Africa’s tropical regions are becoming more unreliable; and places where temperatures are approaching thresholds of human health are urbanizing quickly. Africa’s population has risen from about 250 million in 1960 to 1.3 billion, will add another 400 million (equivalent to the populations of the U.S. and Canada combined) in the next 10 years, and will continue to rise from there.

At the end, the audience was clearly shaken. An expert on African tropical forests asked me if I was being too pessimistic about Africa. I was puzzled. I had organized the findings of climate science and presented them in the context of society, but I hadn’t expressed an opinion. This organization of facts had challenged their worldview. As they walked out, a few scientists said to me some version of “I guess I hadn’t really thought it through.”

What the economists in 2001 and the climate scientists in 2018 had in common was a culture that made it very difficult to believe that really big changes could happen. This difficulty is understandable, both because 12 millennia of climate stability made anything very different from the past hard to imagine and because marginal changes are computationally easier: You can study change in one thing (like a small economy) without worrying that what happens in that country will change everything everywhere else on Earth.

To make this concrete, consider this: How should one even think about the fact that China poured eight times more concrete between 2001 and 2021 than the U.S. did over the entire twentieth century?

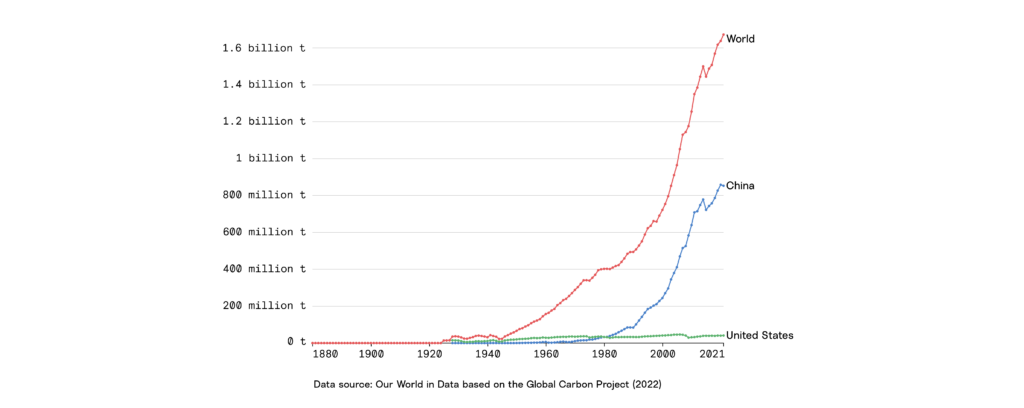

Annual CO₂ emissions from cement

Today there are 41 cities in China, each with more than 3 million people. In the early 2000s, I visited more than half of them. After each trip, Boston felt smaller and less significant. I began to understand how massive human society was becoming and simultaneously how small any one of us was.

The growth I saw in China did not lead me to recommend buying Chinese stocks or bonds. Instead, I started to see how that growth could change the rest of the world—especially the places where people assumed China was irrelevant. I kept hearing I had “bullish” and “bearish” views on things like inflation, bond yields, and working-class incomes in the U.S. and Europe, despite not having any strong opinions or feelings about any of them. “Getting China right” wasn’t principally about what would happen in China, but how what happened in China would defy or wreck the models and frameworks people were using elsewhere in the world.

Cultural models

Economists, financial analysts, and scientists employ technical models that simplify the workings of economic, financial, and physical systems in order to answer questions and make decisions. Most people likely think that models are the province of abstract experts, but every one of us uses models all the time. We couldn’t function if we didn’t.

On our own, we notice patterns and discover heuristics (mental shortcuts) that allow us to make quick judgments and decisions. Other people—parents, teachers, priests, rabbis, imams, gurus, influencers, artists, etc.—offer us ways to understand and react to the wider world that reflect their experiences, beliefs, and values. Moreover, as a psychologist explained to me recently, once we build our mental and emotional models, our psychologies often prohibit us from seeing the world in ways that violate the models we have adopted. Unfortunately, our cultural models are now revealing the same weaknesses that hampered specialized experts.

Climate change is usually portrayed as an industrial problem: The use of fossil fuels, the creation of steel and concrete (production of which makes up roughly 10% of current emissions), and the clearing of forests for farmland began substantially altering the atmosphere beginning around 1850. However, over a decade of working on the topic, I have come to the conclusion that the roots of the problem lie much further back, principally in the Anglo-European models that now dominate but also in aspects of Chinese ones. I see climate change as a problem of old, deep cultural models being overwhelmed by the scale of modern humanity.

To better understand what I mean, let’s look at some models in one of the oldest formats, paintings.

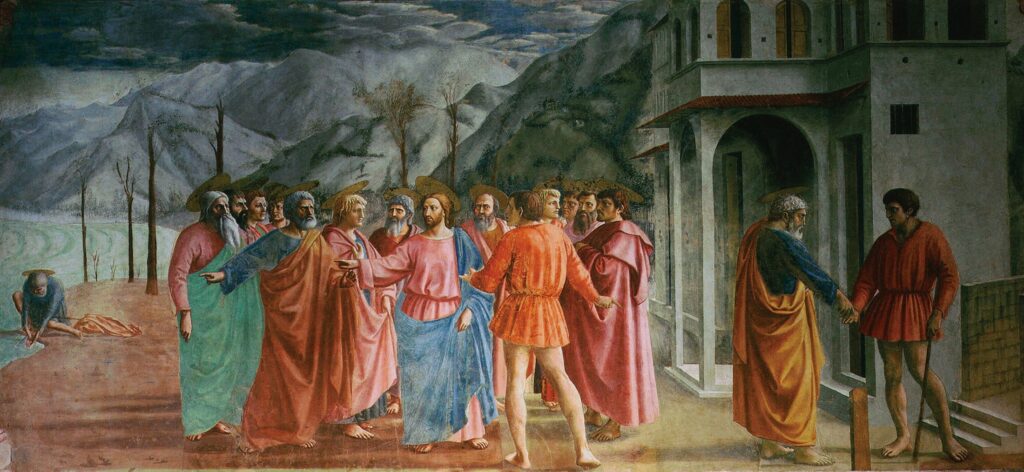

Nature as backdrop: The Tribute Money by Masaccio

Florence, Italy, is known as both “the cradle of capitalism” and the birthplace of the Renaissance. In the 14th and 15th centuries, its wealthy merchants and manufacturers led the creation of a lucrative textile economy across the Mediterranean and throughout Europe, its financiers mastered and promulgated financial innovations including bills of exchange and double-entry bookkeeping, and its artists painted, built, and wrote in ways that celebrated an idealized version of classical antiquity, vigorously asserting that humans were the center of the world.

In 1422, a wealthy Florentine silk merchant and diplomat named Felice (“Happy”) Brancacci commissioned Masolino di Panicale to paint frescoes depicting the life of St. Peter in a newly constructed chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine. After painting began, Panicale was hired away by the king of Hungary, leaving his young apprentice, known by his friends as Masaccio (which translates to “Messy Tommy”), to do almost all of the work. With the chapel as his canvas, Masaccio embraced the ideas of the budding Renaissance with skill and beauty. The life of St. Peter was filled with vibrant people, three-dimensional classical buildings, and natural lighting.

Below is a reproduction of one of the frescoes, The Tribute Money.

In the center, a tax collector demands payment of a tribute tax, and Jesus tells Peter to go to the water and cast a line, assuring him that he will catch a fish in whose mouth he will find the money needed. On the left, Peter is seen removing the coin from the mouth of the fish. On the right, Peter pays the tribute. It’s a beautiful image, and I encourage you to zoom in and look closely, noting the detail of the legs, hands, hair and faces and the colors of the robes. You can almost feel the silk.

There are 19 scenes on the walls of the chapel. Seventeen from the life of St. Peter, and two of Adam and Eve: first, their temptation, and then their expulsion from Paradise. You may think that we’ve wandered very far from economics and climate change, but what I see here is a very deliberate and informative model. The chapel’s frescoes teach churchgoers about the power of God, the perils of sin, the miracles of Jesus, the story of an ideal Christian (Peter), the ideal forms and proportions in architecture (in concrete, by the way, a material that the Florentines embraced), and the unholiness of tax collectors (note his bare legs, shadowy face, and threatening stick).

Renaissance paintings are often as crowded with people as a car would be in one of China’s 46 subway systems today. Yet neither in the time of Jesus nor in the time of Masaccio was either the Middle East or Europe densely populated. Life would have been agrarian, with plants and animals everywhere humans went. But these frescoes were not painted to show life as it was. They were simplified models whose purpose was to teach the stories and values.

If this painting is offering a model for how to think about life, what does it have to say about nature and other beings? That, at best, they serve as an unimportant backdrop or a source of revenue. Masaccio’s ability to render depth, light, and human figures signals the direction that Renaissance art will follow. His abstract background, meager trees, and insignificant (but financially helpful) fish are also precursors to the implicit message that “Man is the measure of all things.”

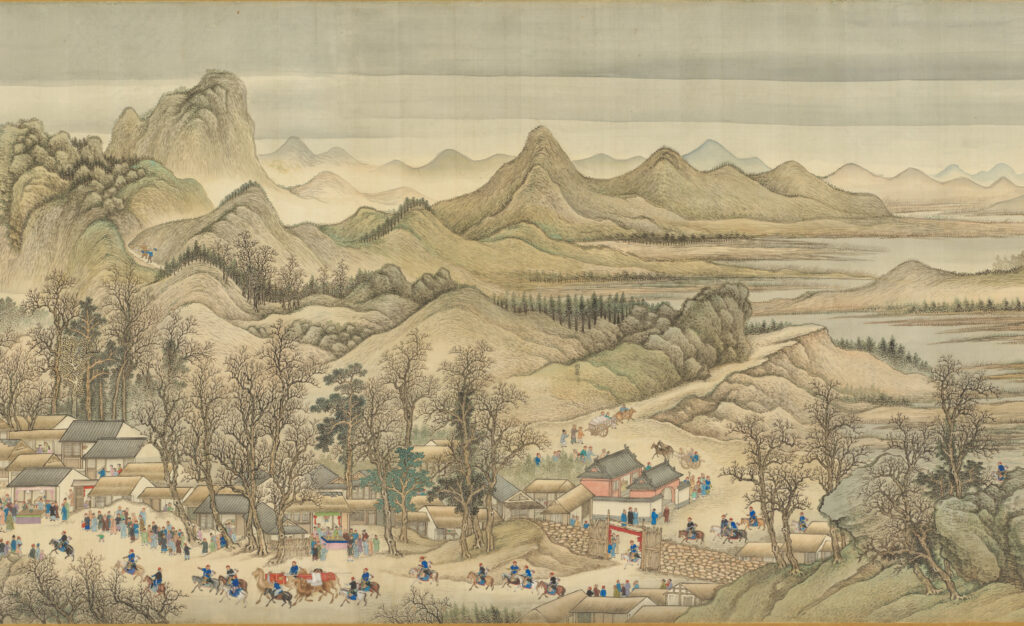

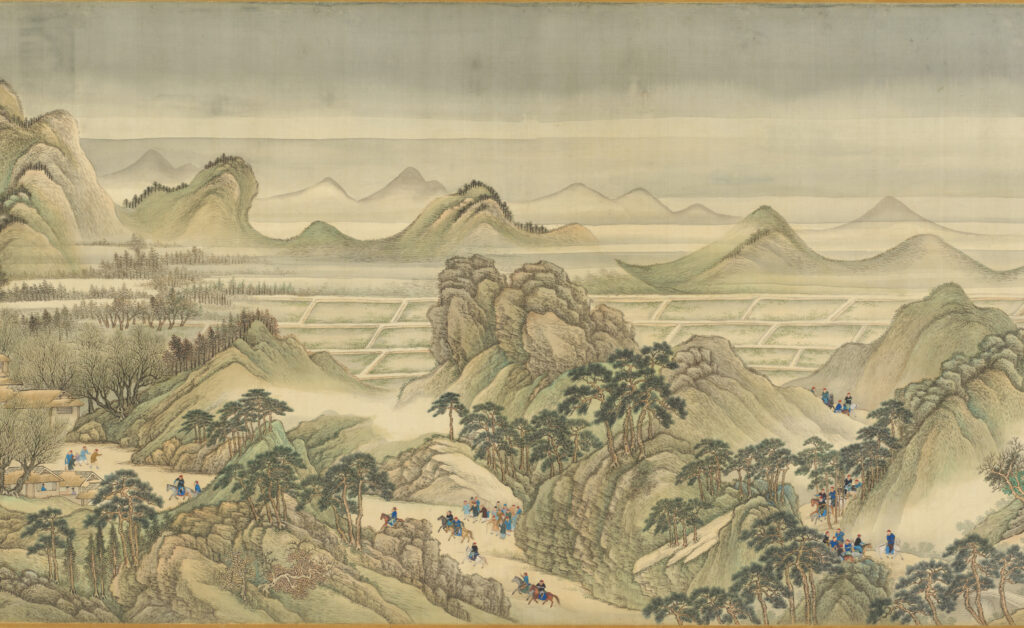

Nature as invincible: The Kangxi Emperor’s Southern Inspection Tour, Scroll Three, Ji’nan to Mount Tai by Wang Hui

In the late 1600s, China was ruled by emperors from Manchuria. In 1698, the Kangxi emperor toured China and asked a renowned painter named Wang Hui to document it. The resulting 12 scrolls are marvels.

At the time of this tour, China was home to about 138 million people. Yet the paintings are not crowded. This is probably pretty accurate, for even though it was home to more than one quarter of humanity at the time, China was a rural, agrarian land, and people lived their lives in the context of plants and animals. In the model of life portrayed by Wang Hui, people do not seem in charge. Instead, nature appears vast, dynamic, and impervious, while people are indistinguishable from one another. I cannot tell if any of them is the emperor.

Here are three panels from the scroll that documents the entourage’s journey to Mt. Tai, the sacred mountain of East China:

When I saw The Tribute Money in 1992 at the age of 23, its human-centrism made perfect sense to me. In contrast, when I saw images like Wang Hui’s in museums when I was young, they were at odds with how I was implicitly and explicitly taught to see the world and myself. They seemed to suggest that a stiff breeze might blow the small people away without the forests or mountains noticing.

In early 2000s China, however, nature seemed anything but impervious. The few times I went to Chinese museums, scrolls like these seemed like they were from a different planet. About 20 million people live within 50 kilometers of Mt. Tai today. Similarly, when I went back to Florence as one of more than 20 million tourists in 2016, the frescoes that had once made sense to me looked alarming: The earthly scenes had at most decorative greenery, and the images of heaven offered no plants or animals whatsoever.

A Damning Perspective: The Beaver Gnaws the Tree by Shintaro Miyake

My wife directs a contemporary art museum. In 2005, she invited the Japanese artist Shintaro Miyake to come to Boston to create an original project.

For each of his projects, Miyake takes on a character and then creates art as that character. This was his first project in North America, and for it he chose a North American character that fascinated him: the beaver.

Miyake immersed himself in the life of this unusual rodent. His wife made him a beaver suit, complete with a giant head and tail. He came during late summer that year, and Lisa and her crew made a movie of him building a dam in the Massachusetts countryside in full costume. After making the movie, he returned to Japan to make art that he thought a beaver would make. He arrived in Boston in the spring to install the show.

When in Boston, he stayed in our home, so I had lots of time to ask him about his process. He explained to me that he was fascinated by the point at which children change their relationship with other beings. When kids are small, they are eager to see the world from other perspectives: They play as rabbits, dogs, birds, flowers, and any other living thing. They wonder, “What would it be like to be a fish?” At some point, though, they are discouraged from doing this any longer. They somehow learn to distance themselves from the physical, natural world. Rabbits, dogs, birds, flowers, and every other living being becomes more of an object, more other. As adults we might ask, “What is a fish?” or “How much money could I get from that fish?” or—more likely—we won’t pay that being any attention at all.

Miyake had decided that there was interesting art to be made by earnestly trying to continue to see the world through the eyes of other things. Here is one of the drawings from the show, Beaver Gnaws the Tree:

I don’t know that Miyake actually learned much about beavers. In fact, Lisa and her colleagues created a small natural history museum in part of the gallery so that people could learn the truth about beavers. What I think Miyake does masterfully, however, is show us what the world would look like if other species thought as we now do. Masaccio might hate the flatness and inconsistent scale of Beaver Gnaws the Tree, but I think this work shares much in common with The Tribute Money. The beaver who painted it is so spectacularly beaver-centric. The only things that matter are other beavers, ponds, and wood to gnaw. People? They are left out completely. Sure, there are some buildings, but they aren’t even colored in. They are just empty shapes drawn in perspective. It doesn’t seem as if humans would survive long in this world. Eventually, the beavers would overwhelm them.

Model criticism: The Nutmeg’s Curse

Amitav Ghosh has written with insight about the human, cultural, and artistic challenges posed by climate change. His slender volume, The Great Derangement, is an incisive exposition of the ways that Western novelists ignored nature in the same way that Masaccio did with biblical scenes, but Ghosh could just as well have been writing about economics, philosophy, ethics, or business. His book that followed, The Nutmeg’s Curse, explores the depths of this derangement, in part by telling the story of nutmeg.

Before trade with and exploration of other lands, European life was bland. Italians didn’t have tomatoes or peppers yet (they would come from what is now Mexico). Northern European food (the Irish didn’t even yet have potatoes from South America) and clothing were mostly drab. So when Dutch people got their first taste of Southeast Asian nutmeg, they went crazy for it. Combined with sugar from the Caribbean, nutmeg was even more delicious.

The combination of Anglo-European human-centrism, fabricated racial hierarchies, and the logic of markets led Dutch colonists to see the Banda archipelago as simply a place for nutmeg. To get the nutmeg, they killed or displaced all of the people on the islands. As anyone who has cooked or baked with nutmeg knows, a little goes a long way. Before long, there was so much nutmeg on global markets that prices plummeted. So the Dutch East India Company acted according to the logic of the market and ordered its subordinates to reverse their behavior and destroy as many nutmeg trees as possible to limit supply. The stories of commercializing “natural resources” continue from there.

I highly recommend Ghosh’s book, not least because he is a wonderful writer. The point of the book, however, is to argue that the model of human-centric, industrial-scale consumption embraced by colonial powers was never viable for billions of people because it would overwhelm nature. Nature is now in serious peril because, as Ghosh describes, almost every nation, no matter how abused it was by colonialism, has now adopted the models—both the quantitative economic ones and the philosophically, human-centric moral ones—that left such scars on both cultures and landscapes around the globe.

Western-trained economists were able to accurately forecast China’s economic growth in the early 2000s because the country was becoming more like their models. This transition was the result of both conscious choice and experimentation by Chinese leaders. After two centuries of turmoil and instability and repeated efforts to find alternative ways to prosper in a world increasingly dominated by countries that had adopted Anglo-European models, China embraced market-led industrial growth along with its measures and values. Gross domestic product (GDP) became the standard of government success and a part of everyday Chinese conversation. It was common for people to tell me about the GDP of their city or province, something I almost never heard in the U.S. On one trip, I met a language professor at a Chinese university. She was kind and interesting, but what sticks with me more than a decade later is her telling me exactly what percentage of the prior year’s graduating class were employed and what their average wages were. The purpose of learning languages was to generate income.

I developed a reputation among some Chinese government officials as an outsider who could help them understand their own country. I was occasionally invited to offer my perspective on Chinese industrialization and the building of a social safety net. My guidance was well received, but when I tried to help these same officials see how powerful China was globally, they did not want to listen. They insisted that, much like the images in the scroll, the country and its people were still poor and small, and that what happened to people and species elsewhere in the world was not their concern.

A missed opportunity to develop better models: The Limits to Growth

Fifty years ago, a group called The Club of Rome assembled people from different fields to examine the future of human, economic, and natural systems. They created a model called World3 to simulate different combinations of population and productivity growth, resource use, and economic activity. The results were published in a book called The Limits to Growth (LTG). The book’s title gives a sense of its message: There are limits. Its scenarios mostly pointed to the 21st century as being when limits would start to be visible, especially after 2010. The book was a huge commercial success, selling tens of millions of copies in many languages. In economics, finance, and what came to be the dominant cultures of the past 50 years, however, LTG was portrayed as a screed based on simplistic, biased assumptions.

Robert Solow, the economist whose work on “exogenous” or unexplained economic growth won him a Nobel Prize, gave a speech at a symposium about LTG in 1973 called “Is the End of the World at Hand?” It is a fascinating read. Solow calls models with planetary limits and human systems that may overshoot those limits “Doomsday Models,” dismissing them outright. His primary arguments fit tightly in the logic of economics: Higher incomes make people better off, and if resources actually become scarce, their prices will rise and markets will react, so nature’s limits will likely reveal themselves in advance of serious trouble. His final sentence, in which he offers an alternative to LTG, is the most important:

I think we’d be better off passing a strong sulfur-emissions tax, or getting some Highway Trust Fund money allocated to mass transit, or building a humane and decent floor under family incomes, or overriding President Nixon’s veto of a strong Water Quality Act, or reforming the tax system, or fending off starvation in Bengal—instead of worrying about the generalized “predicament of mankind.” (quotes are in the original)

Solow’s list of suggestions is strung together with “or” instead of “and,” implying that doing some of these things would be sufficient. The key turn of phrase in his finale, however, is “instead of.” He could have said that we should enact his list of policies and improve upon or offer alternatives to LTG. But Solow’s message was clear, and his opinion proved to represent the strong consensus. Economists, other academics, development institutions, and leaders of countries around the world worked on growth, debated the other policies on the margins, and abandoned the generalized predicament of mankind altogether.

In The Nutmeg’s Curse, Ghosh asks a provocative question:

Would the West have embarked on its reckless use of resources if it had imagined that a day might come when the rest of the world would adopt the practices that enabled affluent countries to industrialize…? If this possibility had been acknowledged, a century ago, then maybe some thought would have been given to the consequences.

Western economists like Solow (who was a strong advocate for eliminating poverty) would surely have objected to Ghosh’s claim that they assumed that “most non-Westerners were simply too stupid, too brutish, to make the transition to industrial civilization.” They would have insisted that they fully intended for the poor countries to grow, for prosperity to spread. But I am confident that Ghosh is right that they didn’t really believe that would happen. In a 2002 interview on the 30th anniversary of LTG, Solow repeats his original criticism and then says this about climate change:

The major practical problem in connection with global warming is how do we deal with the poorer parts of the world? How do we intelligently and equitably deal with the part of the world that is now preindustrial or primitive industrial and is “uppity” enough to think it has every right to live as well as Americans or Europeans? How are we going to tell them we developed economically by burning fossil fuels at a tremendous rate, by partially depleting reserves and by polluting the atmosphere, but then tell them not to?

The obvious case is China, which sits on a vast pile of coal. If they burn it and get to be an economy of a billion people living at a modern standard of living, then we really are in for a problem.

What do we do instead?…. To the extent that we talk in terms of any moral obligation, it’s our obligation as rich countries to find ways for the rest of the world to develop economically with a proper respect for the environment and the dangers that could be associated with global warming.

I think the intellectual foundations for talking about that are still very weak. We have no clear idea about what the regional economic consequences of global warming are likely to be… We need a lot more work on that.

Unlike Solow’s call for inaction in 1973, however, this call for action—made as China poured inconceivable quantities of cement and built new coal-fired power plants every week—went unheeded.

Resisting bad models and searching for good ones

By this point, many readers will have had the thought, “There are too many people on Earth.” Others will have thought, “Capitalism is the root of all of these problems.” I have had these thoughts, too. I have come to the conclusion, however, that given the urgency of climate change and the dominance of a single global framework, we should concentrate on improving existing models and bringing different models together. In particular, economic and financial models need to work within the boundaries of the atmosphere and biosphere, and cultural models need to both take into account the vastness of human power and learn to see nature as neither irrelevant nor impervious but rather as a wondrous system that we can either appreciate and nurture or exploit and destroy.

This is the kind of work that my colleagues and I hope to encourage with Probable Futures. Our knowledge of such efforts will always be limited, but I thought it might be helpful to share a few that I find interesting and useful. None of them offers a complete solution, but all are welcome contributions to an urgent conversation.

Recalibrating scientific and economic models: Earth4All

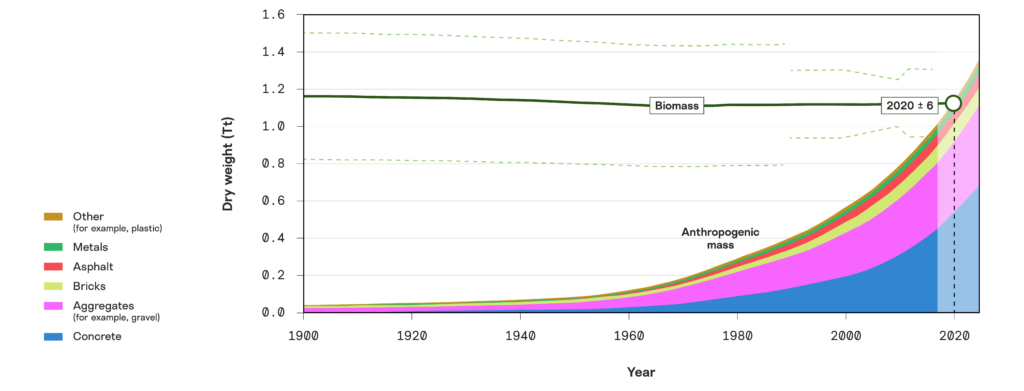

In 2020, a group of environmental scientists in Israel published the results of a simple inquiry whose perspective reminds me of Shintaro Miyake: How big is the human-built world compared with the living world? If you put all of the stuff that humans have made (concrete, bricks, steel, etc.) on one side of a scale and all living things on Earth on the other, which would weigh more? They discovered that around 2020, the mass of human built-stuff surpassed Earth’s biomass.

The weight of the world: estimated anthropogenic mass and biomass

Recently a group of scientists and economists revised World3 with updated systems models that include climate change (the new model is called World5). They have published their findings in a report called Earth4All.

Many of Earth4All’s recommendations are practical ones that Solow made 50 years ago, but that were carried out inconsistently: strong pollution taxes, strong protection of natural systems, and raising the incomes of poor people. They add to their list limits to consumption and wealth and the encouragement of more civic institutions so that people can have multiple ways to address the predicament of mankind.

I have not dug into the workings of World3 or World5 enough to praise or critique them on a technical basis, but among Earth4All’s leadership are two people whose work on systems I admire: the economist Kate Raworth and the ecologist Johan Rockström, both of whom are bringing systems thinking and boundaries into their professions and into our shared culture. I hope that other scholars will pick up on this work and find ways to improve upon it instead of sticking with the models that got us into this situation. I am happy to say that Probable Futures tools and data can help with regional and local implications.

Reconsidering an old cultural model: Laudato Si’

In 2015, Pope Francis released an encyclical entitled Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home. Francis explains near the beginning that popes typically write encyclicals for the members of the Catholic community, but in this case, he is writing to all people, regardless of their beliefs.

Here are a couple of passages.

On the dominant socioeconomic, technological, market framework:

Men and women have constantly intervened in nature, but for a long time this meant being in tune with and respecting the possibilities offered by the things themselves… Now, by contrast, we are the ones to lay our hands on things, attempting to extract everything possible from them while frequently ignoring or forgetting the reality in front of us. Human beings and material objects no longer extend a friendly hand to one another; the relationship has become confrontational. This has made it easy to accept the idea of infinite or unlimited growth, which proves so attractive to economists, financiers, and experts in technology.

On the complexity of the problem and the value of many models:

Viable future scenarios will have to be generated between… extreme [models of techno utopianism and human extinction], since there is no one path to a solution. This makes a variety of proposals possible, all capable of entering into dialogue with a view to developing comprehensive solutions.

I recommend Laudato Si’, both on its own merits and as an example of a person trying to take his own community’s models and reorient them. Francis searches the bible, the work of St. Francis of Assisi, and more recent messages from bishops in Brazil, Japan, and other non-European lands to convince the reader that the necessary ingredients for addressing climate change and ecological destruction can be found in a proper, fresh reading of his church’s teachings. In essence, he argues that Masaccio misinterpreted the scriptures.

New models on campus

Before I accepted the job at Wellington, my favorite adviser, an esteemed economic historian, tried to convince me that I should take a very good assistant professor position that I had been offered. I explained to her that I was excited by the prospect of working on a range of issues and figuring out new things and that, although I had gotten a Ph.D. in economics, I was a generalist by nature. “You can be a generalist as a professor,” she replied. “You just need to focus on one narrow thing for seven or eight years, and then you can start working on other things.”

The modern university model has a few key features, each of which makes climate change an unwelcome problem, and each of which contributed to my choice to take the Wellington job instead of a professorship: 1) Scholarship is backward-looking by definition, so there are no disciplines oriented toward the future; 2) Huge categories are divided into separate schools (arts, sciences, engineering, medicine, business, etc.); 3) Within schools, departments rarely interact (physics and biology are far apart; economics has nothing to do with either); and 4) Within fields, careers are made out of specialization.

A few years ago, a scholar named Roy Scranton started the Environmental Humanities Initiative at the University of Notre Dame. As Scranton says in a video on the initiative’s homepage, climate change “is an issue that we continue to understand primarily through a scientific framework, and yet it’s an issue that cannot primarily be addressed through a scientific framework. It’s a political issue, it’s a social issue, it’s an issue of justice, it’s a philosophical issue, so there is a deep, deep need to bring together the sciences, the humanities, the arts, and the social sciences, bring them into dialogue, collaborate, and work across the disciplinary boundaries that keep apart these different kinds of knowledge.”

When we started Probable Futures three years ago, Scranton’s initiative was the only one of its kind that we knew of. To the extent that universities were addressing climate change at all, it was as a narrow science or engineering problem. Indeed, we chose to work with the Woodwell Climate Research Center instead of a university because at Woodwell, scientists across disciplines meet every week and collaborate regularly. It has been an excellent partnership.

In the past couple of years, universities have started feeling pressure from students, alumni, and the public to take climate change more seriously, to offer leadership, and to prepare students and society for a future that will not be like the past. In essence, these constituencies are challenging their institutions to either prove that their Western, specialist, backward-looking model can adapt, or change their model altogether. A few are now responding, with splashy announcements of new initiatives and centers. But there is a huge amount of work to do, much of it cultural, within the universities themselves.

Recently, a group of European business school leaders published a kind of Laudato Si’ in the Harvard Business Review for what might be called the churches of business. The authors identify aspects of business education that can be extremely helpful in addressing climate change (business transformation, performance measurement, managing operations, marketing, organizational leadership, incentives, and governance) if they are oriented to do so. It ends with: “The urgency of the climate crisis demands that business schools experiment with new ways to quickly and effectively collaborate.”

I am happy to say that a number of institutions have reached out to Probable Futures and me to help them in these endeavors. Probable Futures is now used in professional climate education resources like Terra.do, we have done workshops with education scholars who are working on curricula for learners at all levels, and I accepted an invitation to be an Executive Fellow at Harvard Business School to help create cases, workshops, and curricula using Probable Futures that can be taught to students, executives, and all interested parties around the world.

Encouraging model behavior

My hope with these letters is that they encourage readers to find ways to incorporate an understanding of climate change into their work, their lives, and their ways of seeing the world. I appreciate that doing so challenges almost all of our models and even violates other ones altogether, but the rewards can be great. My collaborators and I—all of whom have reconsidered aspects of our lives—have consistently found joy, wisdom, clarity, and a feeling of “I think I knew that as a kid but somehow forgot it” when someone showed us a better way to see the world. The goal of Probable Futures is to help other people make paintings, write books, develop television shows, build spreadsheets, write memos, create lesson plans, or simply tell stories of people, fish, taxes, trees, farms, concrete mixers, or anything else that helps us think on both human and non-human scales.

If you need a place to start, here’s one: Recently, scientists have managed to reawaken interest in beavers. It turns out that beaver dams help clean water, restore aquifers, trap carbon, and encourage myriad other forms of life. Before European colonists hunted them to make hats, there were perhaps 100 to 200 million beavers in North America. In recent decades, there has been some recovery of the population, to perhaps 15 million. Thankfully, if we learn from beavers, their behavior can be both encouraged and emulated. Beaver restoration projects are underway in several states in the U.S., as are man-made dam projects inspired by beaver techniques.

Thank you for reading this letter on the equinox. Everyone on Earth gets 12 hours of daylight today. I hope you enjoy them.

Onward,

Spencer

Reading and watching:

Business schools must do more to address the climate crisis from the Harvard Business Review

Ted Chiang’s short stories illuminate our mental frameworks better than any author I know. His collections Exhalation and Stories of Your Life and Others are fantastic. The story “The Great Silence” is told from the perspective of a parrot. I think about it all the time.

I recommended Omar el-Akkad’s first book, American War, in my March 2021 letter. His more recent book, What Strange Paradise, presents the moral dilemma of climate change–induced migration in an elegant, conventional story of a few people trying to figure out how to live well.

Roy Scranton’s short book Learning to Die in the Anthropocene is hard and dark but also liberating and useful.

The Probable Futures team is curious about the new series Extrapolations on AppleTV+. One of the writers and producers, Dorothy Fortenberry, said something we now share in every presentation: “If your story doesn’t include climate change, it’s science fiction.”

View The Kangxi Emperor’s Southern Inspection Tour, Scroll Three: Ji’nan to Mount Tai at The Met