Greetings on the December solstice. Today, 42° north of the equator, the deciduous trees are leafless. Eleven years ago, my wife, Lisa, and I planted a ginkgo tree in our small backyard. It shed its golden leaves early this year, despite a warm November, stashing the summer’s bounty in its trunks and roots for the winter. While the tree stands bare in the face of shorter, colder days, Lisa and I feel the urge to nestle and hibernate like bears.

A couple of months ago, government leaders, climate activists, journalists, and opportunists gathered in Glasgow for the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26). Much has changed these past 26 years. Most significantly, the amount of CO₂ in the atmosphere above ground has risen 20%, and the amount of methane (CH₄, a.k.a. “natural gas”) in the atmosphere has risen 15%. On Earth, there is much more activity and concern about climate change than ever before, with new communities, coverage, and commitments emerging with increasing frequency. One thing that hasn’t changed much, however, is how we communicate about climate change. Which brings me back to bears.

Out of curiosity, I googled “climate change images.” I was shown a preview of 10 photos, half of which contained polar bears. In Glasgow, there were larger-than-life polar bear statues, people in polar bear suits, and papier-mâché polar bears in life vests. Some of them looked fun, some were charmingly amateur, and at least one was impressively fabricated. I wondered, however, why the people who put effort into making these displays and traveling with them to Scotland thought they would be effective. What was it about polar bears that might change human behavior?

This is not a snarky question. Every day, the Probable Futures team works to figure out how to reach people to help them envision what is coming, prepare for what we can’t avoid, prevent as much suffering as possible, and imagine better ways to live in an unstable, warmer world. As I considered protesters in their polar bear suits, I became aware of the presence of bears in my earliest childhood and decided to learn more about how bears became part of American and European culture. What I learned turned out to be instructive.

Entertaining Bears

I can’t recall my parents reading Winnie the Pooh or Paddington Bear stories to me when I was very small, but they must have, as I associate those tales with the warm feelings that attend happy childhood memories. These sweet, ursine characters are the inventions of A.A. Milne and Michael Bond, respectively. It made me wonder, what motivated these two English authors to write about bears? Could they have seen wild bears in England?

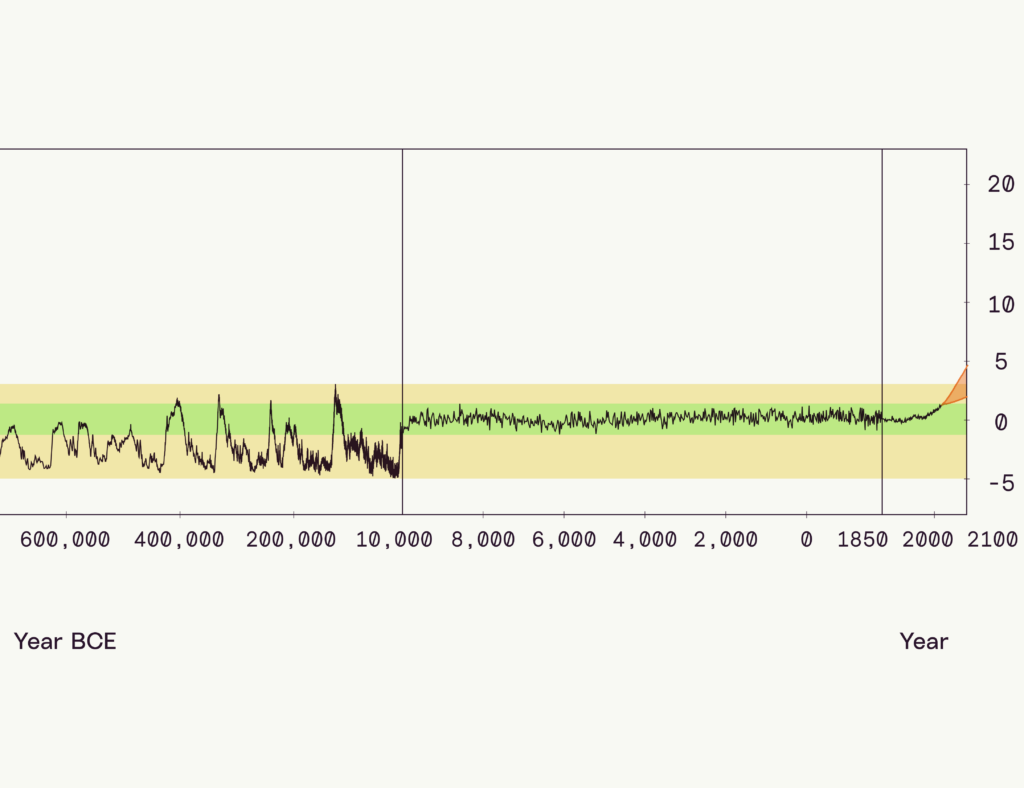

It turns out that before the last glacial maximum, brown bears were abundant in the British Isles. Then, 30,000 years ago, when much of the archipelago was covered in ice, polar bears and reindeer roamed the land. When the climate warmed to the stability we have enjoyed for the past 12,000 years, the species that relied on very cold weather disappeared, and black bears and other large mammals flourished again. As the human population grew and developed tools, however, forests were cut down for fuel and farms, and black bears went extinct, likely around 3,000 years ago.

After the Romans conquered much of Britain in AD 43, they reimported bears to the British Isles. It turns out that the Romans had captured bears in the remaining European forests. They trained relatively lucky ones to dance and absolutely unlucky ones to fight dogs while tied to a post in front of spectators, a tradition called bear-baiting. They brought these amusements with them to conquered territories. After the fall of the Roman Empire, dancing bears seem to have fallen out of favor, but British monarchs retained a love of watching chained bears fight, building arenas for the pastime. In the 19th century, this tradition finally died out, and bears retreated to being mostly folkloric characters.

The bear that inspired Paddington’s creator, Michael Bond, was not a wild bear but a lonely-looking teddy bear in a London shop window in 1958, by which time it was common for stuffed bears to be toys for little children. I had a stuffed bear as a child. He was a steadfast companion for years, and then served the same role for my younger sister, Christina. A few years ago, she found the imaginatively named “Brown Bear” in our parents’ home and gave him back to me. Christina’s and my love left him with one eye, lots of missing fur, and many exposed stitches. Somehow his state of wear and exhaustion conveys a full life of generosity and stoicism.

Teddy

There might never have been a teddy bear without an energy crisis. In spring of 1902, the Mine Workers of America went on strike. Coal was king, but unlike other big industries, coal was more labor- than capital-intensive, and thus workers had power. President Theodore Roosevelt threatened to deploy the military to end the strike, but eventually he met with union representatives and mine owners, and they finally worked out a deal in November, before winter set in. Tired and stressed out, Roosevelt (who apparently hated being called Teddy) wanted a vacation. He accepted an invitation from the Mississippi governor to go bear hunting.

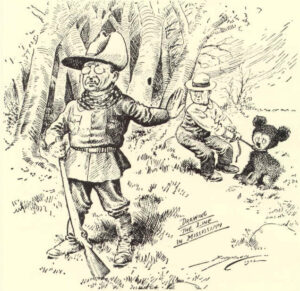

After three days without spotting a bear, Roosevelt was frustrated. His group’s guide, Holt Collier, a former Confederate cavalryman who claimed to have killed 3,000 bears in his life, finally tracked down an old, female black bear. Instead of killing it, he had his dogs attack it, and then clubbed its skull with his rifle after the bear killed one dog. He and his men then tied the bear to a tree so that the President could have the honor of the kill. By all accounts, the bear looked miserable when Roosevelt arrived at the scene. The President decided that it wouldn’t be honorable for him to shoot it. The story spread in the coming weeks, turning into legend. A cartoonist in the Washington Post showed a cute, healthy bear being shown mercy with the caption “Drawing the line in Mississippi.”

The moral was clear: Roosevelt was powerful, but at a critical moment he knew to show restraint. Nature needed to be respected and given its due; the line had to be drawn. So popular was the story that a couple who owned a Brooklyn store created a plush bear and put it in the window with a tag titled “Teddy’s Bear.” Barely a month later, teddy bears were the must-have gift for Christmas.

I don’t want to undermine the charm of teddy bears, but the rest of the story is instructive for understanding how we got to where we are with climate change. The message the cartoon sent was that good people would leave space for nature to be wild and dignified. In truth, however, although Roosevelt didn’t kill the bear, he instructed Collier to cut its throat with his knife. Humans do care about wildlife, and our leaders enjoy being associated with morally flattering narratives, but nature has almost always lost when faced with any competition for our modern desires, including stress relief. When we have turned to nature, it has generally been to take something from it, not to give something back. That is an increasingly dangerous mindset.

Just right

Another bear story of my childhood is that of Goldilocks and the Three Bears. I heard it referenced many times in school and later at work, usually simply as Goldilocks, in reference to something that was ideal. It is now sometimes invoked in the context of an ideal climate. For those who don’t know it, here is a synopsis as I learned it:

A golden-haired girl is walking alone through the forest and comes upon a house. She knocks on the door, and when receiving no answer, lets herself in. There she discovers a set table with three bowls of unattended porridge. She dislikes one because it’s “too hot” and another because it’s “too cold,” but finds the third to be “just right” and eats it all up. She sees three chairs, finds one too hard, another too soft, and a third “just right,” although her sitting on it breaks it to pieces. She then goes to the bedroom where there are three beds, one of which is also “just right,” and falls asleep. The owners of the home are three bears, a Poppa, a Momma, and a child. They come home after a walk they took to let their porridge cool and discover the theft of their porridge, the destruction of one chair, and the continued home invasion, and are alarmed. Goldilocks runs away with no apparent consequences.

I’m not sure what I was supposed to take away from the story, but contemporary American society associates it with knowing what you like and finding what’s “just right.” This, it turns out, is an excellent metaphor for the climate we have destabilized. It was absolutely just right for us.

Too hot

Starting about 10,000 BCE, the earth’s atmosphere stabilized around a mild average temperature, with slight variations. Those variations, both over time and across space, were in a range much like the porridge in the story. The “too hot” porridge was not boiling, let alone on fire or charred—it was just warmer than Goldilocks preferred. Similarly, while some places on Earth were warmer than you or I might have preferred, nowhere on Earth was so hot as to be lethal to humans, and indeed, some people preferred hot places, their bodies having adjusted and their customs, clothing, and architecture having adapted. But there is a limit to what we can adapt to—every person’s body only functions in a specific range of temperatures and humidities. When the air is high in humidity and too close to our body temperature, we overheat. For the history of civilization, and likely for the history of humanity, however, nowhere on Earth ever got too hot for us.

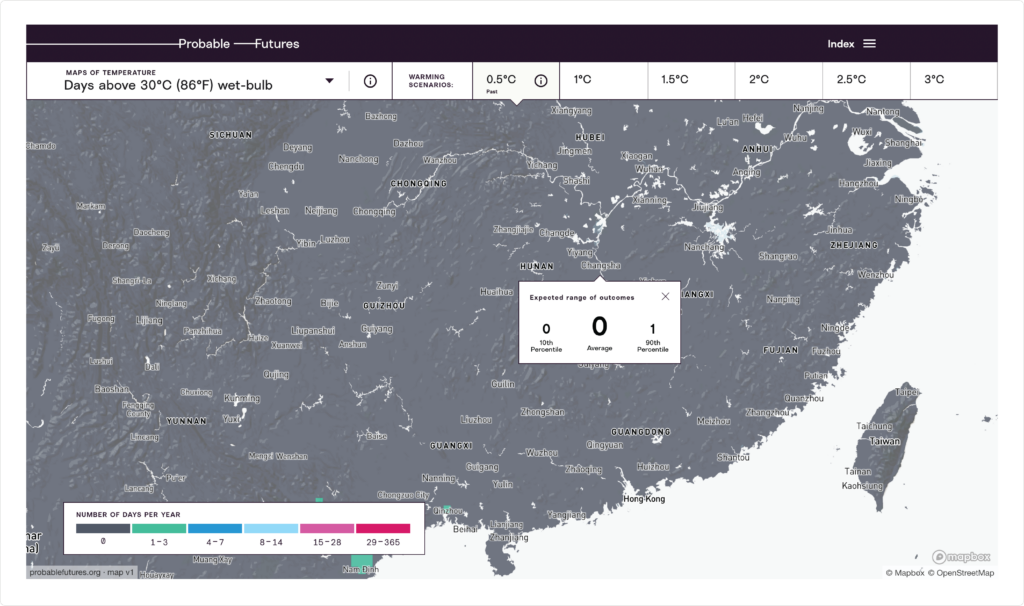

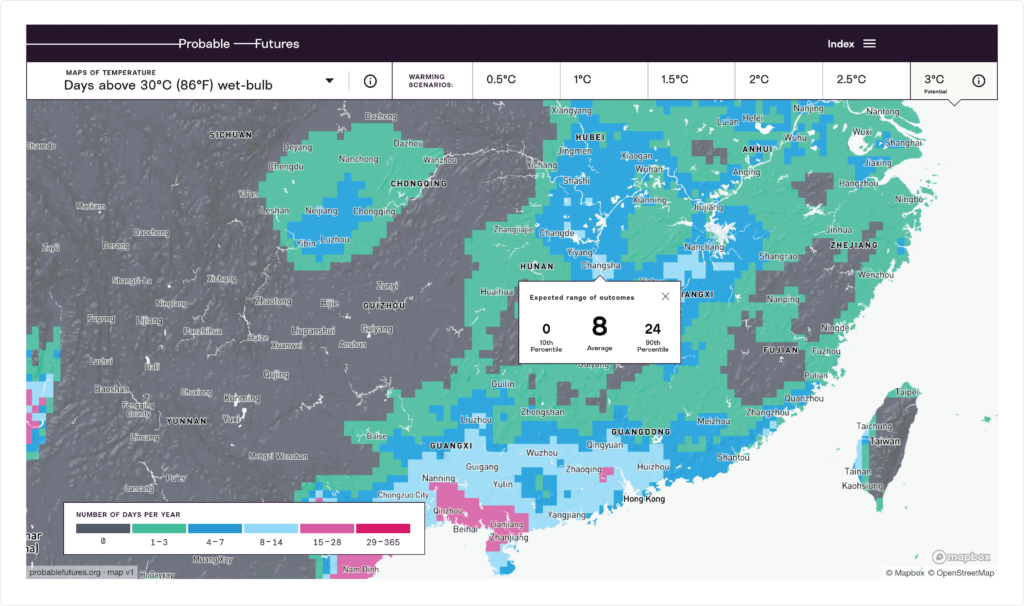

As a result of us burning fossil fuels and felling forests, we are approaching thresholds in parts of the world at which “too hot” won’t be an expression of our preferences, but a medical diagnosis. In the late 20th century, when the atmosphere was 0.5°C above the long, stable average we enjoyed, we only experienced 30°C wet-bulb (equivalent to 30°C/85°F and 99% relative humidity or 38°C/100°F and 54% humidity) for one or two days a year in a few locations in South Asia and the Persian Gulf. Elsewhere, people couldn’t even imagine weather that hot.

In 2000, I planned to travel to the Chinese city of Wuhan in September. I spoke decent Chinese at the time, and a friend said to me, “Wuhan is one of the four somethings of China.” I italicize somethings because it was a word I didn’t understand. After the conversation, I went to my dictionary and looked up the word phonetically. It meant “furnace.” It turned out that Wuhan, Chongqing, Nanjing, and Changsha were called “The Four Furnaces” because they were so oppressively hot and humid in the summer. A former colleague of mine went to university in Wuhan. She told me that the heat was so unbearable in the dormitories that she and the other students slept (or tried to sleep) on the roof in September.

The Chinese use of “furnace” to describe uncomfortably hot weather is like Goldilocks’s “too hot.” Until recently, 30°C wet-bulb (which is measured in the shade with a breeze) was impossible in any of China’s so-called furnaces. Now, however, the set of models Probable Futures incorporates show that we’ll likely pass this brutal threshold in an average year in Chongqing, Wuhan, and Changsha, the last of which is the smallest of the furnaces, home to only 5.5 million people (10+ million in the metro area). If the atmosphere warms from today’s 1.2°C above the preindustrial average to 3.0°C, Changsha should expect eight such days in an average year, and more than three weeks in a warm year. It will truly be “too hot” for people: potentially lethal for the old, the ill, and the very young to be outside, and dangerous even for strong, healthy people, as their kidneys will have to work incredibly hard to handle the nearly fruitless sweating induced by such heat.

Not cold enough

In the Arctic—one of the coldest regions on Earth—it is warming faster than anywhere else, just as scientists foretold. I encourage you to explore Canada and Russia on Probable Futures maps. You can see the change in the average temperature of the ten hottest days, the creep of days above 32°C (90°F) into places that had previously never seen them, and the shrinking number of days that stay below freezing. The maps can help you understand why Arctic sea ice, on which polar bears depend, is declining so rapidly. We have much in common with polar bears and the few wild mammals that remain on Earth. Just as the receding ice indicates the shrinking boundary of their habitat, rising temperatures are likely to shrink our habitat—and retreating ice will be one of the reasons.

What I didn’t understand until I started working on climate change was that sea ice is fundamental to human civilization. Climate stability was possible because a stable quantity of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere trapped a nearly constant amount of radiation and because Earth received a steady amount of energy from the sun. The key to that energy consistency was ice. Look at the picture below and just note the contrast:

Water is dark and absorbs almost 100% of the sunlight that hits it, while snow-covered ice reflects sunlight back to space. Less sea ice, fewer glaciers, and less snow cover on mountains mean that our system is taking in more energy than at any time in the past 12,000 years. More heat has led to less ice. Less ice in turn means more heat. The cycle repeats. This is a feedback loop.

When I look at this polar bear with an understanding of climate change, the emotion that it conjures isn’t sympathy, it’s empathy. The bear is learning what “too hot” means, while we are failing to see it for ourselves.

Communicating differently

The original Three Bears story wasn’t about what Goldilocks wanted for breakfast, or what kind of memory foam mattress she wanted delivered to her door with the bonus of free shipping thanks to the discount code from the podcast she listened to. It was about restraint. Three good, proper, kind bears live together. They make porridge for breakfast and take a walk while it cools. A nasty old crone comes by the house, sees the nice things inside, enters, and goes through their porridge, their chairs, and their beds. When the bears come home, she jumps out of the window and is punished. (In one version she is impaled on the spire of St. Paul Cathedral; in another she is imprisoned.) In subsequent versions, the old woman is replaced with a girl. Here is the last paragraph of this version on americanliterature.com:

When she saw the Three Bears on one side of the bed, she tumbled herself out at the other, and ran to the window. Now the window was open, because the Bears, like good, tidy Bears, as they were, always opened their bedchamber window when they got up in the morning. So naughty, frightened little Goldilocks jumped; and whether she broke her neck in the fall, or ran into the wood and was lost there, or found her way out of the wood and got whipped for being a bad girl and playing truant, no one can say. But the Three Bears never saw anything more of her.

Unlike the Goldilocks story I was told, the consequences of invading bears’ habitats were grave in the older versions. That turned out to be prophetic as we now face the grave consequences of cutting down forests and using the atmosphere as a dump for our emissions. The rich countries of the world have done a terrible job of restraining their abuse of nature while doing a fabulous job of developing preferences about what constitutes “just right” for individuals.

Probable Futures is an endeavor to communicate differently. Most importantly, it is an effort to help and motivate people to tell stories that matter to them and might resonate with others, be they about cities, children, food, new businesses, policies, or any number of things our team could never imagine. What we hope is that the writing, photos, illustrations, and maps you can find at probablefutures.org will inspire fables, poems, novels, memos, Powerpoint presentations, movies, music, and more to connect and inspire us.

The novelist Richard Powers has taken on this challenge. His magnificent book The Overstory affected many people deeply. Writing it affected him as well. I recommend listening to his conversation with Ezra Klein, which I will link to at the end of this letter. In Powers’s new book, Bewilderment, a young boy is obsessed with the decline in animal species on Earth. He learns that more than 96% of mammal life on Earth is now either human or livestock, and he is devastated. Driving back from a stay at a cabin in a pocket of virgin forest in the Great Smoky Mountains, he and his father run into a traffic jam. Dozens of cars have stopped to gawk at a mother brown bear and her two cubs walking at the edge of the woods. The boy is furious with the gawkers, who care deeply about bears in this one moment but will quickly forget and do nothing to protect nature once they drive away. “Why don’t they just leave them alone?!” the boy cries to his father. “They’re lonely,” the father replies.

I think that’s correct. In cumulative, escalating efforts to control the world around them and shape it to meet their desires, many societies have pushed away wild things, as if humans could live on this planet alone, ignoring the myriad natural forces that created the climate in which we thrived. Disinterest in other life has left us with a fragile climate and terrifyingly few earthly companions. Perhaps, ironically, black and brown bears have done somewhat better than most other species thus far. In North America, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, there are still hundreds of thousands of them. They have been able to eat some of our garbage and, being “uncivilized,” have found it easier to migrate with the changing climate than we have.

Forests and trees

When Lisa and I planted our ginkgo 11 years ago, we wanted it to serve us. It was a beautifully symmetric juvenile tree that seemed likely to shade us in the increasingly hot summers. We placed it strategically so that it would block our view of the ugly utility pole on the edge of our small lot. That one-time tree, stripped of its bark, has dozens of wires tied, stapled, and fastened to it, many of which carry internet and cable to our neighbors’ apartments, many more of which are no longer attached to anything. For two decades now, neither the telephone company nor the cable company has been willing to accept ownership of the pole. At one point, someone planted it there, but now no one claims responsibility for it or is willing to maintain it.

Many corporations are doing something similar now, only at a grand scale. Under pressure from the activists at COP and elsewhere, in anticipation of regulation, and in hopes of making their employees and customers feel warm and fuzzy, they have declared an intention to “get to net zero.” The easiest, fastest, and likely cheapest way to get there is to pay someone to plant trees and take credit for all of the carbon those trees will theoretically sequester in the future. Some very large companies now claim to have “gotten to net zero” in a matter of months. They haven’t changed their day-to-day practices, they simply tout that their continued emissions are now “offset” by the growth of trees they will never see. Unfortunately, recent assessments of massive planting efforts have found that most saplings die long before growing into anything like trees, let alone compensating for fossil fuel use elsewhere.

When I first connected with the Woodwell Climate Research Center, the excellent scientific organization behind Probable Futures’s maps, I spent a couple of days visiting with many of the scientists individually to learn about their research. One area of the Center’s expertise is the measurement of forests. I spent a fascinating couple of hours with a scientist who had, with a colleague, taken satellite images of forests and matched them with observations on the ground. The two of them had spent years tromping their way through African and South American rainforests, northern boreal forests, and everything in between, measuring trunks, canopies, and undergrowth. With this first-hand, hard-won data, they were able to calibrate the satellite data so that future satellite imagery could accurately measure what was happening in forests over time, including how much carbon they were holding in the leaves and trunks.

In China, I had seen newly planted forests. After clearing the land for “productive” use, the Chinese had seen how the deserts were spreading, topsoil was blowing away, and climate change was getting worse. So they set out to plant tens of billions of trees. I asked the scientist, “What can you tell me about the new Chinese forests?” “They aren’t actually forests,” he replied. “What do you mean?” I asked. “They tend to be more like tree farms. The trees are all one species, and they are further apart than they would be in an actual forest. As a result, the trees don’t support each other, share resources, or protect one another in storms. We can see them fall down in winds that wouldn’t affect an actual forest.” In the past couple of years, evidence has mounted that new “forests” in China are predominantly in areas that are drying because of climate change. This makes it hard for young trees to live, while trees that make it to maturity and develop deep roots, most of which are not native to the location where they were planted, are reducing water availability for the native plants. There are similarly discouraging results from India.

Paying someone else, somewhere else, to plant a new “forest” satisfies the modern, industrial, consumerist inclination to “do something.” The most common question I get about climate change is, “What should I do?” My first answer is always, “Exercise restraint: Find ways to stop doing things that you know are making the problem worse.” The second is, “Connect with other people in your community, no matter how big or small, so that you’re not all alone.”

When I speak with CEOs and other corporate leaders, I try to help them see that paying another company to plant trees and convey a sense of moral fulfillment may be as comforting as a teddy bear, and it likely allows people to keep doing what feels just right to them, but it is unlikely to do nearly as much good as exercising actual restraint and giving space to nature. I then tell them something that I learned from another Woodwell scientist: Big trees actually sequester more incremental carbon than small ones do, as they have more surface area, have deeper roots, and are more integrated into their community. The moral of the story has become clear to me: Leave as much space for wilderness as we can; with the leadership and assistance of Indigenous people, work to expand wilderness; and when we plant new trees, do so on terms that are consistent with nature, not the stories we tell ourselves.

Getting through and looking ahead

Lisa and I are resisting the urge to hibernate by taking walks in nearby parks and preserves. Almost every acre of New England’s forests were cut down between the 17th and 20th centuries, whether for fuel, farmland, or timber. Left alone since then, however, they have largely grown back. Indeed, the regrowth of these forests offset a meaningful amount of emissions from coal-powered industrialization.

The woods do something alchemic to Lisa’s and my COVID-heavy moods, making us feel somehow less lonely and more connected. We can’t see the marvelous network of fungi beneath our feet, moving energy and nutrients through an underworld of organisms, but we can feel something deep, and we occasionally see animal tracks. At home, I worry a bit about my ginkgo. Like my worn Brown Bear, the ginkgo is a generous and steadfast companion, but I know that it is less resilient and will not live as long as it would have in a community of living trees. Nonetheless, I am grateful to it and find inspiration in knowing that its kind are hardy, having found ways to survive over 290 million years.

As 2021 draws to a close, I want to wish you, your families and communities, and your organizations well. Our team at Probable Futures is hard at work on additions to the platform, including the second volume—Water—which we are very excited about, as well as a tool that will allow people to take any spatial data, visualize it on Probable Futures maps, and combine it with climate data. We think that mapping coffee farms, outdoor stadiums, power plants, summer camps, or whatever else interests you along with various measures of climate change will help you imagine, develop, and tell data-rich stories. Perhaps motivated and connected by a wider diversity of stories, we can come together to postpone and manage the unavoidable futures we face, and avoid the unmanageable ones that loom. As I have written in previous letters, we are hopeful.

Thank you for your interest in Probable Futures.

Onward,

Spencer

Recommendations:

The Ezra Klein Show (Sept 28, 2021) Richard Powers on What We Can Learn From Trees. The New York Times.