Over the years, I’ve come to understand that climate change is not, in fact, a technological problem but one of relationships. It is the result of the disintegration of our relationship with the natural world, with other humans alive today, and with future generations.

We built Probable Futures to create a resource that examines both the practical and profound aspects of climate change and to offer up a new framework for thinking about it. But for years, while I worked on climate change—and worried about it—my framework was purely practical. My vision for “solving” it was a world in which we supply our energy demands with alternative, non-emitting sources, with not much else changing. Furthermore, having understood the scale of collective action required to address climate change, I was resigned to the idea that my best option was to wait for that collective action to reach me.

That was, until I had the time and space to slow down, read, and listen to voices who are thinking and living differently than most of us in modern life.

This period was partially brought on by a debilitating back injury that left me home-bound and, at times, entirely bed-bound over the course of several months. In a desperate state of pain, with limited options for activity, and yearning for new perspectives, I spent my days reading, watching lectures, and relearning facts that I knew intellectually but had never really let sink in deeply:

- Earth has warmed by 1.2°C since preindustrial times.

- It has warmed ~1°C in my lifetime.

- Global emissions are still increasing.

- Current policies still align with a rapid rise in global average temperature, ratcheting up to 3°C over the course of the next several decades.

- My children are 6 and 9 years old.

- Life has to change.

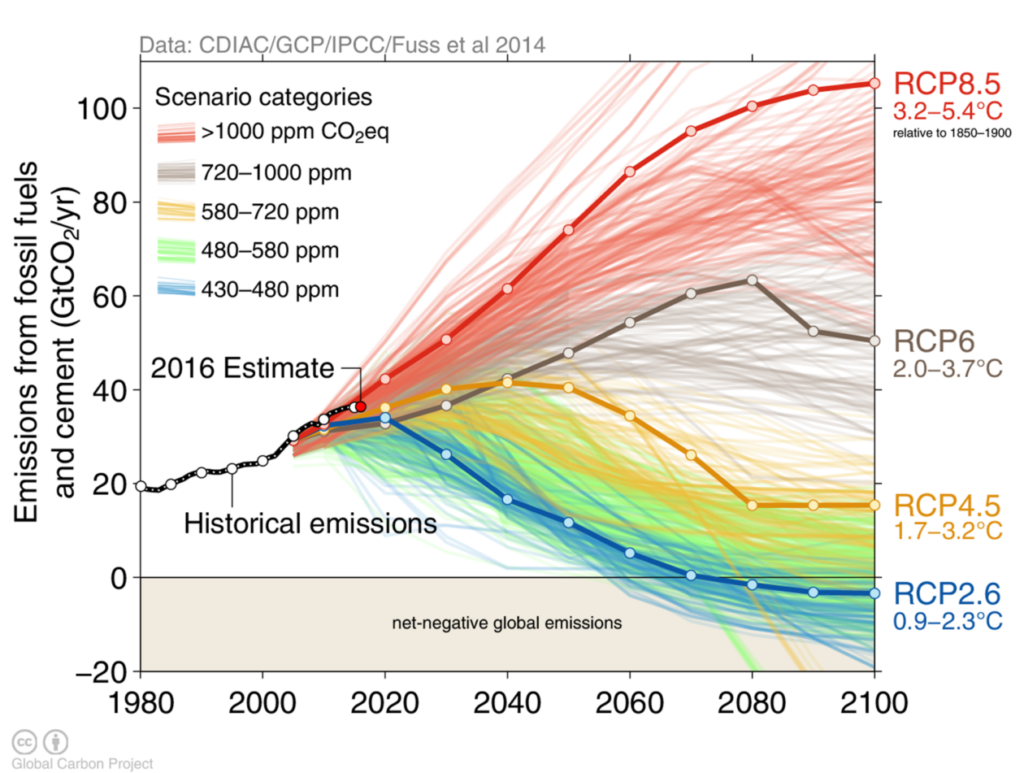

There were times when I sat and simply stared at charts like this, internalizing both the science itself and what it meant.

I grappled with uncomfortable realities about how we got here and why we haven’t done more to address the crisis. In doing so, I had to face both my own outsized contribution to climate change as a person of economic privilege (a privilege that is the legacy of long-standing systems that favor white people like me) and my adoption of a cultural narrative that perpetuates ideals of success that are rooted in materialism.

To me, this chart sends a clear message that if we are to limit global warming, at the scale and in the timeframe that is necessary, we will be living differently, eating differently, and doing business differently. But if we don’t address climate change at the scale necessary, change to our lives, diets, and organizations will still certainly come, and it will come for all of us. It will come for the most privileged, and it will hit the least privileged—and least responsible—the hardest. Life is going to change. Fortunately, we still have the opportunity to choose change by design, rather than by desperation.

But is this scale of change realistic? Are we intractably committed to our current ways of life? To these questions, evidence from the past made me more hopeful about the future.

History shows us that society is capable of great change, at a large scale, even in short periods of time. While technological advances precipitated many of these shifts, there are examples of cultural change being driven simply by the evolution of values. From the age of enlightenment to the establishment of international humanitarian laws to the civil rights, feminist, and LGBTQ+ movements in the United States and other parts of the world, we can draw inspiration from moments when we knew we could be better.

One person in particular who has influenced and inspired my thinking about the future is Rev. Mariama White-Hammond—a spiritual leader, community organizer, and now Chief of Environment, Energy, and Open Spaces for the City of Boston.

At a 2019 event, I was struck by her reflections that modern society is largely missing a concept that is fundamental to our species:

We have lost touch with the basic reasons for why we exist… the notion that at the end of the day, the one thing we are called to do is to make sure that the next generation survives.

Rev. Mariama makes the case that the practical solutions to climate change at scale will never come without a profound shift at our core—a shift that recognizes our connection and responsibility to people living near and far from us, geographically and temporally.

The evening took place at the Woodwell Climate Research Center campus near the illustrious science community of Woods Hole in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The audience was largely a mix of young scientists, established scientists, and retired, affluent people, many of whom were spending time in their second or third home. Woods Hole has a notorious housing challenge for many people who work in the area, while nearby vacation homes sit unoccupied for several months out of the year.

The discussion period at the end of the program turned to this subject. Eventually, Rev. Mariama asked those in the audience who had vacant bedrooms in their homes and would be willing to share those resources to raise their hands. A few went up. Then, she asked for anyone who struggled with housing to do the same. As the program attendees that evening shuffled out the door, three or four groups stayed behind, exchanging contact information and arranging times to meet and work out details of home-sharing. What was happening felt natural—perhaps even familiar.

If we are really going to address the climate crisis, we need an evolution of the human heart. We will need to be better than we have ever been. This is an opportunity to become the people we imagined we should be but never quite had the courage to become…We have an amazing opportunity to create the systems we hope for as we watch the systems that have already existed be unable to answer the call of this moment.

With Rev. Mariama’s words ringing in my ears, I started making changes in my life that are mindful of the physical and societal realities of climate change. My family began to significantly reduce our emissions and we also began to experience both the benefits and tradeoffs of living a life that is framed by climate awareness. I know that it will be a long and iterative process for us and for society to get to zero. None of us can do it completely alone, but knowing what we do about the consequences of climate change, we need to start being better than we have been.

As my health improved, I was given the opportunity to start building something new with my mentor, collaborator, and friend, Spencer Glendon. Together, and in partnership with Woodwell, we assembled a small team of dedicated scientists, designers, engineers, and writers. Our intention was to do what we could, within our power, to answer the call of this moment.

With this initiative we strive to support the many climate change movements already underway—particularly the ones that are led by young people and vulnerable communities on the front lines of climate change. Our goal is to become a trusted and transparent resource by providing access to climate science. And we could see that there was an opportunity to give all people encouragement—and tools—to envision futures that are truly worth hoping for.

As we launch the first phase of Probable Futures, our team is filled with anticipation to see how we can work together to answer the call of this moment.

Welcome to Probable Futures.

Alison Smart