By now, everyone reading this letter has likely heard of ChatGPT, the software that can write birthday cards and term papers, might be able to fall in love, and perhaps heralds the beginning of the end of civilization. Having been fed books, academic journals, and portions of the internet, the software predicts, literally one word at a time, what we want to read or hear when we ask it a question. Large language models (LLMs) like GPT4 (which powers ChatGPT) are “generative pre-trained transformers,” and as such, they are the latest, most advanced effort to do something humans have undoubtedly been doing for thousands of generations: Take the stories of the past and transform them into insights that can be useful in the future.

In a way, the computer scientists working on AI are the successors to the traditions of oral historians, griots, and bards. For millennia, those esteemed women and men passed on tales and legends to help individuals and communities make good decisions and live well. The promise of AI models is that if they are fed all of our stories, they will be able to discern patterns and reason their way to truths that we couldn’t discover on our own (or at least not as quickly, cheaply, or profitably).

It’s apt that most of these LLMs are being built in the United States and the UK because the English language has a specific tense that gives subjects a sense of permanence and truth: the habitual present. This verb tense sounds like the present tense but implies not just “is” but also “was” and “will be.” “California has a mild climate,” “Chinese people eat very little meat,” “Humans are the only beings that have emotions,” etc. It is the verb tense of authority, the one that ends a debate: “That’s the way it is.”

But what if the experiences of the past are just the way it was? What if they don’t tell us the future? What are the risks of looking to the past for guidance, treating it as a source of truth, and even insisting on it as a forecast? Moreover, how do we behave when we know that we have left the past behind? Might there be better ways both to study the past and to deploy computer models?

The Way We Live Now

I have no particular insight into the power or prospects of AI models and their applications, but the current hubbub about them brings to mind an old satirical novel by Anthony Trollope, The Way We Live Now, in which insecure British nobles and intellectuals, fearing the prospect of losing their comfortable (often idle) ways of life to industrialists and financiers, willfully abandon norms and standards that previously defined their culture. They behave in ways that they know are unseemly, but because everyone else seems to be doing the same, they convince themselves that perhaps they aren’t so wrong. The addition of Now at the end of the title is a small stroke of genius. Trollope makes it clear before we even open the book that we didn’t used to live the way the characters inside do, and we need not do so in the future.

Trollope was conservative by nature, and The Way We Live Now, which was serialized in magazines as he wrote it, feels nostalgic, as if the author yearns to return to a pre-industrial, pre-financialized past; however, its lessons are timeless and even feel current. British Lords and Ladies are animated by the prospect of getting shares of a San Francisco–based company that is pioneering a new technology (railway) that stands to generate huge fortunes. Each of the characters has options available that would allow them to live honorably (if perhaps more modestly), but the threat of losing their social status and the lure of life-changing wealth are too much for them to bear, so they flout traditions and morals to flatter and fête a dubious financier.

A well-read colleague recommended the book to me in 2000 shortly after I had taken a job at an investment firm. I told him that the culture of finance was unfamiliar to me and that I was looking for ways to understand it. He said that Trollope had written as well about finance—and the effect money has on people—as anyone. This proved true, for as I was about to witness, changing financial prospects can destroy traditions, not just in Britain.

Cultural revolutions

In 1999, the investment firm hired me to help them figure out East Asia. I had just received a PhD in economics, and had experience in banking, but to do this job well, I was going to have to understand not just economics and finance but China. I dutifully sought out China experts (many of whom were known as “old China hands”), both in print and in person. They told me about a populous but unimportant, closed, cryptic, fascinating, largely static country, invariably employing the habitual present tense: “China is a country of villages,” “The family is the key institution in Chinese life,” “The Communist Party controls everything,” “Chinese is an old culture that resists change,” etc.

And then I started spending time there, traveling across the country, talking with all kinds of people. What I witnessed were brand-new cities, husbands and wives living apart and sending their kids away, entrepreneurs taking big risks, and people adopting new habits with amazing speed. The lure of money was bending the culture in bizarre ways. While in graduate school, I had studied Mandarin Chinese to be able to speak with my in-laws, but stable familial pleasantries had not prepared me for this dynamism. I knew that the language had no genders, no cases, no verb conjugations, and no past or future tenses, but I hadn’t appreciated how this simplicity could make it so hard to understand change.

Everything in Chinese is effectively in the present tense, with modifiers to indicate time: “I eat watermelon” could mean “I am eating watermelon right now,” or “I am a person who eats watermelon.” “I eat watermelon yesterday” indicates that the action was in the past, while “I eat watermelon tomorrow” places the eating in the future. China was careening into a very different future, with radically different habits, and when I made a discovery or came to understand something, I couldn’t tell whether I had a valuable insight or whether I was simply witnessing the way people were living right then.

In my March 2023 letter, I wrote about how hard it was for economists and investors to believe that China would be as enormous and influential as it quickly became. I think there is another lesson to be learned from that era. Leaders of the Chinese central bank and the fledgling national pension program, many of whom were quite young, began asking me if I would come share my views with their teams. They were acutely aware that they were facing challenges for which their own experiences and those of the Chinese government offered little insight. China had been in one crisis or another since Westerners attacked China in the Opium Wars in the 1830s, so stable patterns were few. But the 25 years of peace and investment in basic infrastructure and schools under Communist rule meant that the country was poised for something new. Much to my surprise, I had deep knowledge of a history that was relevant and could prove helpful.

To my eyes, 2000s China looked a lot like US urbanization and industrialization between 1850 and roughly 1990. It wasn’t a perfect match, but there were lessons from America’s past to inform China’s future, except China seemed poised to cross the same economic and cultural span in as little as 20 years. In the US, however, academics remained uninterested, and those who studied Chinese economics continued to look backward. This was not just an academic issue, as corporations and governments were trying to decide how to interact with the country. For example, economists continued to insist that China entering the World Trade Organization would not be disruptive for American workers, because history had shown that the growth of small, closed, technologically underdeveloped economies “is a net positive” for developed countries. There was that habitual present tense.

History as pattern

I was talking through some of the ideas in this letter with my friend, Paul Fleming, a professor at Cornell who leads the Society for the Humanities there. Paul is working to bring climate awareness into the humanities and humanities into other disciplines. He said he’d been thinking about something similar: how a transition from antiquity to modernity had been accompanied by a change in the way people talked about, thought about, and used history. In particular, he was exploring how stories and anecdotes had lost their status in history.

Paul explained that at least as far back as ancient Greece, history was passed on by orators whose tales offered examples from which to draw lessons. Paul shared an essay titled Historia Magistra Vitae (“History as teacher of life”) in which Reinhart Koselleck describes this ancient approach as one where “history is presented as a kind of reservoir of multiplied experiences which the readers can learn and make their own; in the words of one of the ancients, history makes us free to repeat the successes of the past instead of re-committing earlier mistakes in the present day.” This is not history as a blueprint or a set of rules but as a store of stories in which we might find something of value.

Koselleck argues that this ancient framework persisted into the 18th and 19th centuries, at which time history started to be considered a pattern from which to discern arcs and rules. In German, this transition was from the word die Historie, which was comprised of episodes, anecdotes, and examples, to die Geschichte, which implied structure and meaning.

Koselleck calls 1750–1850 a “saddle period” during which ancient forms were replaced by modernity. During that same time, scientists in what became physics, chemistry, and biology discovered properties of the physical world that turned out not just to be habitually present, but permanent, consistent, and powerful. The industrializing world was both changing quickly and becoming predictable. These findings in the natural world motivated many scholars to seek similar, fundamental, unvarying truths about people, both individually and as groups. Over time, different approaches emerged and were codified into economics, sociology, anthropology, psychology, and political science: the social sciences. Interestingly, history was sort of left in between the humanities and the sciences.

Insuring the future with the past

Perhaps the most explicit expression of climate stability in the modern world is the way insurance policies, engineering standards, and other codes refer to a storm, drought, fire, flood, heat wave, or other phenomenon that has a 1% chance of occurring in a given year: “1-in-100 year.” These events were not called “1% chance” events most likely because few people were comfortable with the language of statistics, but in a stable climate, substituting probability (% chance) with frequency (years) wasn’t much of a distortion: If something happened on average once a century in the past, it could be assumed to have the same probability going forward. As you have undoubtedly noticed, however, 1-in-100, 1-in-500, and 1-in-1,000 year events are happening rather frequently. This is a problem for insurance markets.

Insurance is a basic foundation of the modern financial system and thus modern life. As a result, it is a highly regulated industry. In the US, every state has its own regulator, and these regulators (many of whom are directly elected) determine not only the rules of the market but often even the methodologies and prices. In California, for example, calculation of fire risk and expected losses must be based only on past data.

In 2021, the president of the Personal Insurance Federation of California, an organization founded by Farmers Insurance and State Farm to lobby on behalf of the industry, wrote an article for the Ecology Law Quarterly about risks to the wildfire insurance industry. The gist of the article is captured in this paragraph:

While the current, backward-looking rating method may have worked in the past, it cannot account for how escalating wildfire activity is already increasing the amount of money needed in the insurance system to fund rapidly increasing insured losses. If California law will not permit insurers to develop rates using advanced scientific understanding, such as recognition of changing seasonal rain patterns, then it is likely that insurers will choose to limit issuance of policies in high-risk areas where insurance rules make it difficult to obtain adequate prices. Reliable catastrophe models that account for various risk factors––such as vegetation type and moisture, topography, housing density and location, and wind conditions––are currently available to insurers. California insurers use such models for internal analysis and decision-making, but California law bans use of these tools to develop catastrophic wildfire pricing.

In other words, insurers might be able to price insurance correctly using models that account for climate change, but they are required by law to use one model that we know is wrong: history.

I doubt many people read this article, but it was a warning. This May, State Farm, which at the time insured more California homes than any other company, stopped accepting applications for homeowners insurance in the state. The company said it couldn’t price appropriately because the probability of fire and costs of rebuilding had risen and the reinsurance market (insurance for insurers) was drying up.

Implicit in the above quote is the idea that using “reliable catastrophe models” would allow the market to function, but it’s not at all clear that that’s true. Insurance is typically available for risks with low probabilities. Many new risks simply aren’t going to be insurable. This raises the question of the value of properties that no one will insure.

Governments trying to reverse time

A few years ago, I appeared on a public radio show in Florida. The hosts asked me about the prospect of insurance markets shrinking in the state. I explained why I expected insurers to stop offering policies in some areas. The show’s other guest was the former insurance commissioner of the state. He reassured the audience, many of whom were calling in to ask about their property values, saying that, although reinsurance was disappearing, Floridians could still get insurance at that moment, and that it was possible for a housing market to exist without a commercial insurance market—just look at California.

This summer, Farmers Insurance stopped offering policies in Florida. The Republican-led state government has responded by saying that markets and models are wrong. Florida will be fine. Unfortunately, an increasing number of Floridians need to have flood insurance in order to get or keep a mortgage. Many homeowners are discovering that their lender can force them to get additional insurance (force-placed insurance). So the government is stepping in.

In 2002, the Florida government created Citizens Property Insurance Corporation. Citizens’ mission is to “efficiently provide property insurance protection in Florida to those who are, in good faith, entitled to obtain coverage through the private market but are unable to do so.” Florida advertises itself as aggressively pro-business, but to keep its property markets afloat, it is insisting on faith and declaring that the insurance business, which is now incorporating climate change, doesn’t know what it’s doing.

California is at the other end of the American political spectrum, but party ideologies that developed in a stable climate have a way of evaporating in the face of climate change. California’s version of Citizens is called FAIR, which was established “to meet the needs of California homeowners unable to find insurance in the traditional marketplace.” FAIR is funded by a tax on all insurance companies that offer property insurance in the state. Essentially, any Californian who has insurance from a company like State Farm or Farmers is paying a subsidy to those who don’t. This may help explain why, instead of just retreating from specific, risky locations in California, State Farm stopped offering policies to anyone in the state.

The FAIR website is a fascinating artifact of a changing climate. At the bottom of the “About” page, in a smaller, paler font than the rest of the site, is this paragraph:

In the last decade, more Californians have turned to the FAIR Plan as wildfires have devastated California and some insurers have pulled back from these markets. While we will support homeowners regardless of a property’s fire risk, unlike traditional insurers, our goal is attrition. For most homeowners, the FAIR Plan is a temporary safety net—here to support them until coverage offered by a traditional carrier becomes available. We lead with our customers’ interests at heart and reach success when we are no longer needed.

“Regardless,” “attrition,” “temporary safety net,” “until.” These are keywords in the emerging climate lexicon. The final sentence implies that when the old habits, patterns, models, and insurers return, FAIR will no longer be needed. But it can also be read as recognition that if people give up trying to live in increasingly fire-prone areas because mortgages aren’t available, local governments can no longer afford to rebuild, and property values collapse, FAIR won’t be needed. That “either it’s solved and we go back to the way we used to live, or we retreat and find new places and ways to live” verb tense? That’s called the future conditional. It’s the verb tense of climate change.

Putting faith in models

After 15 years of working in the social science fields of finance and economics, I decided to learn about climate models. I was startled by how well they had performed outside of the range of known history. In finance, models that were slightly better than random guesses over six months were incredibly valuable, and macroeconomic economic models that were rarely right more than a year out were still vital inputs. Climate models, however, weren’t being used by anyone, despite having accurately predicted a suite of outcomes including not just average global temperature but changing seasonal patterns, rising oceans, melting sea ice, and increases in both flooding and wildfire. I started calling them “mankind’s first good forecast” and committed myself to bringing their insights into forums where people make decisions.

I am fully aware that turning from known history to unfamiliar climate models for guidance will not be easy. Perhaps not least, such a change will alter our relationship with the past. Earth’s climate was so stable for thousands of years that all cultures internalized past patterns as guides to the future. Trusting imperfect models from specialists to tell us about the future is disorienting and anxiety-inducing.

One piece of good news is that the enduring, permanent lessons of climate science are easy and intuitive. Here are what I consider to be the main ones:

- Carbon dioxide and methane trap heat in the atmosphere, so burning more fossil fuels, cutting down forests, and practicing soil-depleting and beef-intensive agriculture lead to more heat.

- Warmer air can hold more moisture, so a warmer atmosphere causes more evaporation (drought) and can produce heavier rainfall (deluge).

- Ice reflects sunlight back into space, while ocean water and land absorb it, so decreasing ice cover leads to more heat.

- All humans generate heat and need their bodies to stay at a steady 98°F (37°C) to be healthy, so the atmosphere needs to be cool and dry enough for us to off-load our heat.

- Similarly, all other living things on the planet adapted over long periods of time to thrive in specific conditions. The faster those conditions change, the more of them are likely to perish.

My experience collaborating with people from many different walks of life and roles in society tell me that it is particularly hard for technical experts in economics and die Geschichte to resist describing the past in the habitual present tense. When a group of economists recently estimated the future costs of climate change, they looked to the past. Here is the key sentence from their article:

Using a panel data set of 174 countries over the years 1960 to 2014, we find that per-capita real output growth is adversely affected by persistent changes in the temperature above or below its historical norm, but we do not obtain any statistically significant effects for changes in precipitation.

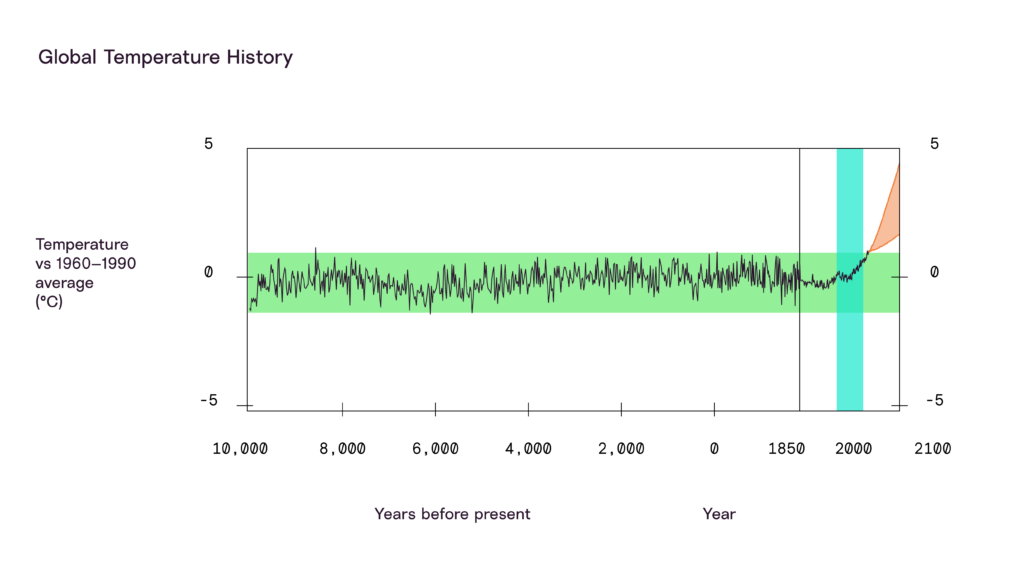

The graph below shows that the period between 1960 and 2014 was very similar to the previous 12,000 years, while the period ahead (they consider a scenario that ends up far past 3°C by 2100) is well outside the temperature band of civilization.

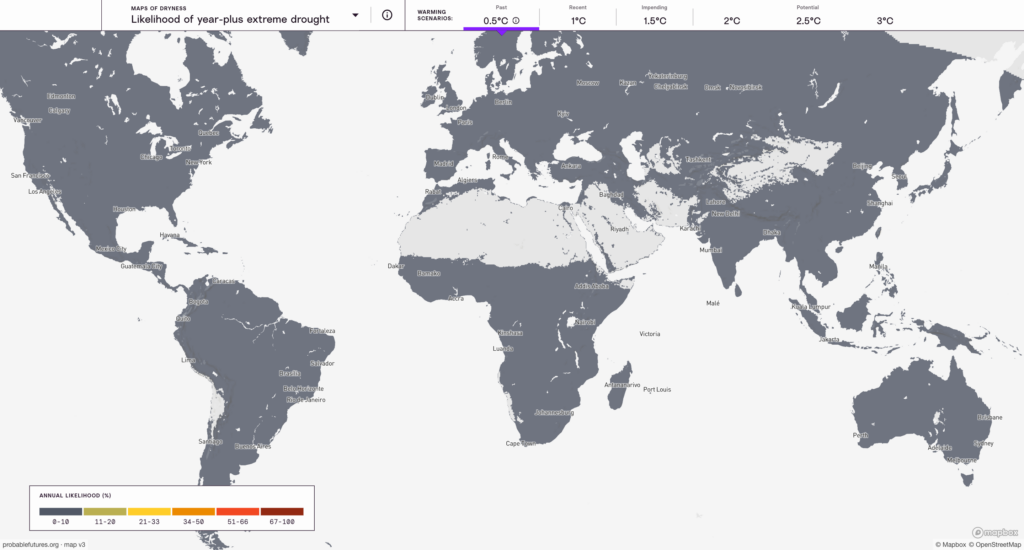

The article reports no statistically significant effects from changes in precipitation. Let’s consider the climate of 1960–2014, when the average temperature was about 0.5°C above the pre-industrial average. Here is a map of the annual likelihood of extreme drought at 0.5°C:

Everywhere on the map is gray, because an extreme drought was extremely unlikely.

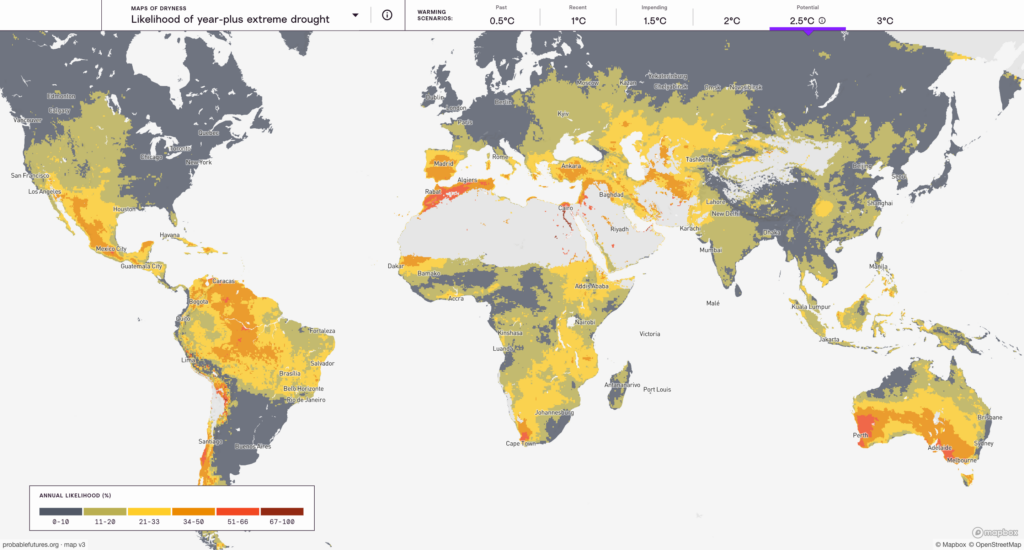

How likely would such a drought be at 2.5°C of warming (lower than levels projected in the paper)?

If we reach 2.5°C of warming, the yellow places on this map should expect to be in a year-long extreme drought 21–33% of the time. Orange places, 34–50%. In red areas, what was rare would now be more common than not.

The abstract says that output “is adversely affected by persistent changes in temperature” (habitual present tense). Even the effects from temperature they do find, however, are small. Looking all the way out to 2100 in a 3°C world, increased heat would cost the world economy just a few percentage points of GDP.

That warmer future, however, will pass thresholds. Consider 30°C wet-bulb, a temperature that is extremely dangerous for human health. Around 0.5°C of warming, it almost never happened anywhere in the world. I have highlighted Guangzhou, China, which had about one million residents in 1960 and about 15 million today. Guangzhou is a hot place. In an average year in the past, no days would have passed 30°C wet-bulb, and in a warm year there might have been one such day:

If we get to 2.5°C, however, Guangzhou should expect eight days that pass that threshold in an average year, and more than a month of such perilous days in a warm year, while areas where hundreds of millions of people live right now will experience these unprecedented temperatures regularly.

I want to be clear: I think studying the historical effect of weather on output is potentially insightful. It is helpful to know how little weather seems to have affected economic activity in the past. It just might not tell us much about the future. I would suggest rewriting the paper’s abstract as: “During a period of climate stability that was within the bounds of the previous millennia, changing weather did not matter much. This tells us very little about a future in which weather will be substantially different. Indeed, our results offer a potential warning: After a long period during which weather was irrelevant to economic output, economic systems may be unprepared for climate change.”

This brings me back to AI, which has been fed the corpus of academic literature with its penchant for the habitual present tense, its bias toward the past 50 years (when data was available), its ability to only see outcomes (not intentions), and its strong bias toward the US and Europe. I suppose AI’s training included some Confucius and Lao Tzu that an idealist uploaded to the internet, but I strongly suspect the lessons of sages, griots, and philosophers represent only a small number of bits in the education of LLMs. I doubt it senses the satire in Trollope’s The Way We Live Now.

I often think of my one meeting with Mark Zuckerberg. I asked him if his experience had given him special insight into human nature. He replied in the habitual present tense, “No. People like what they like, and they like what their friends like.” In a way, it’s a tautology that is hard to argue with, but in another way, it’s a dangerous framework that is likely to exploit the aspects of human nature that are most manipulable. Such a framework does the opposite of what good history and storytelling offer: Instead of helping us do difficult things that bring us lasting well-being, joy, and pride, it makes it easier for us to do things we “like.” Which do we want to pass on to future generations?

The difficulty of being young now

The mental exercise I have found most consistently helpful since I first worked in China is wondering what the future looked like to a young adult in the past, the present, and the future.

From roughly 5000 BCE to the 18th century, children almost everywhere in the world could see the future in the lives of the adults around them. Almost all of them lived in agricultural communities, just as their ancestors had and their descendants would. Adults had a small range of professions. Lessons about duty, wisdom, folly, and shame, as well as instructions about what to cook and eat, whom to marry, what to expect from a spouse, a friend, an in-law, a child, a brother, etc., and how your role in society would shift as you aged, changed very slowly if at all. There was great consistency from generation to generation, and parents could speak to children in the habitual present tense.

Now consider a child entering her final year of high school in China in 2023. She most likely lives in a large or enormous apartment building in a huge metropolitan area. She has no siblings or cousins, as both she and both of her parents are single children. She is connected to the internet during every waking hour, and she has the keen sense that the world is both highly competitive and highly uncertain. Roughly 60% of her peers will go on to tertiary education next year.

What can this girl’s elders tell her about her life? How can they prepare her? How can she prepare herself? Who will help her? When her grandparents were her age, they lived in a village, and all the universities in the country were closed due to the Cultural Revolution. When her parents were her age, they lived in a small Party-owned apartment block next to a factory, and tertiary education was available only to a few. Like elders everywhere, Chinese mothers and fathers often speak about the past. My Chinese is not good enough to know, but I have the sense that in this specific case, English may be a more descriptive language. Because it has a past habitual tense, there is a precise and melancholy way to talk about the past. So many things “used to be.”

In my work, I spend time with people in what are often called “senior leadership” positions. Getting such people to take climate change seriously remains challenging. It hasn’t mattered during their career, and both economic experts and financial markets tell them not to worry much. Nonetheless, they are often quick to boast about their (usually small) efforts to do something “sustainable” and to explain how hard it would be to do more. Before our time together ends, however, they often bring up their children. Over the past few years, I have heard dozens of stories of kids studying ecology, working in an ocean lab, or who are “really into sustainability.” I ask these proud parents an impertinent question: “Is your daughter stupid?” They are indignant. “No! She’s brilliant!” I use that opportunity to suggest that they start asking their kids for advice, or maybe just put them in charge.

I have not been to China in more than a decade, and my knowledge of both the country and the language has deteriorated. The country is on the other side of a saddle, but the future may only be saddles from here on out. Yet the all-powerful Standing Committee of the Chinese Politburo is made up of seven men over the age of 60. (In the US, we are likely to choose between two men born in the 1940s when we vote for President next year.) My hope for young people in China and everywhere else is that old people recognize that they may no longer be good stewards. One piece of advice I offer every group of decision makers is to look around the room: If everyone is over the age of 40, you’re probably not making good decisions.

My wife and I live in Boston, near many universities, and every year we encounter more Chinese young adults in the local cafes, shops, and restaurants. Most of them are here to study computer science and economics, fields that their parents think are safe investments. But even experts have little idea what jobs will be well-paying in the future, which will pay poorly, and which will disappear at the virtual hands of AI. I hope they are studying at least some literature and history. I hope they are learning stories that help them imagine other ways of living, because I don’t think America’s past or present now offers a forecast of China’s future. I don’t think anywhere does.

I have explained why I am wary of backward-looking empirical models, and Probable Futures is built to help people look ahead, yet I keep finding myself turning to history. When I look back now, however, it is more in the spirit of the classic stories of American, European, and Chinese antiquity (I know very little about other old cultures). In anecdotes and examples, I look for what Paul Fleming taught me are called exemplars: people and behaviors that illustrate and even serve as models, not of good or bad fortune, but of strength, fairness, justice, compassion, perspective, creativity, and beauty. Tales from cultures everywhere in the world—as far back as both oral and written traditions go—may hold valuable lessons for us to consider as we address the future.

Common language

I find solace and encouragement in aspects of human life that both bring joy and are uncompromised by climate change or other threats. Perhaps the foremost of these is music. At the end of an essay about heavy matters of language and time, I think I should hand the mic to Stevie Wonder.

Here are the opening lyrics to “Sir Duke” from his Songs in the Key of Life album:

Music is a world within itself

With a language we all understand

With an equal opportunity

For all to sing, dance, and clap their hands

But just because a record has a groove

Don’t make it in the groove

But you can tell right away at letter A

When the people start to move

They can feel it all over

They can feel it all over people

They can feel it all over

They can feel it all over people, oh, yeah

Music knows it is and always will

Be one of the things that life just won’t quit

But here are some of music’s pioneers

That time will not allow us to forget

For there’s Basie, Miller, Satchmo

And the king of all, Sir Duke

And with a voice like Ella’s ringing out

There’s no way the band could lose

Take a listen. It’s a great reminder that life can be wonderful.

Thank you for reading my letters and for whatever you are doing to make the future better for young people and other species.

Onward,

Spencer

Reading suggestions:

Lily King’s novel Euphoria is about anthropologists in South Asia in the early 20th century. The characters are trying to capture ways of living that they know are on the cusp of becoming past tense. There is also a love triangle.

Claire Keegan’s novella Small Things Like These tells a story of exemplary behavior embedded in coal, laundry, and family.

William Julius Wilson’s When Work Disappears is perhaps the most prophetic piece of scholarship about American culture from the 1990s. He saw what was coming.

Ha Jin writes fiction in English that sounds and feels like Chinese. It’s remarkable. I have not kept up with his writing since the early 2000s, but I loved the short stories in Ocean of Words. An excellent essay on the relationship between Wikipedia and AI. I am fascinated by Wikipedia and view it as one of the best pieces of the internet. We consulted folks at Wikipedia when we were designing Probable Futures. I found that I preferred to listen to this article rather than read it (plus, the audio version is not behind the New York Times paywall and can be found on any podcast platform).