Climate change can be seen all around us in the form of more extreme droughts, floods, blizzards, hurricanes, and heatwaves. The relationship between air temperature and moisture is at the root of most of these hazards. Warm air is “thirstier” than cold air, able to absorb and hold more water vapor like a sponge.

This is true everywhere, from a fogged-up bathroom mirror to a muggy summer day. As greenhouse gas emissions warm our atmosphere above its historic norm, the air in the atmosphere is holding more and more water vapor. This dynamic can fuel extreme and unpredictable weather, and as global average temperatures continue to increase, it becomes exponentially more powerful. Understanding what drives unpredictable weather can help us anticipate future trends and plan for them.

The Clausius-Clapeyron equation

Full of open holes that act as vacuums, a sponge not only holds a lot of water but also sucks up water from surfaces. In the case of our atmosphere, the air is the sponge, pulling from any available liquid water on Earth’s surface, including oceans, lakes, damp soil, leaves, and your body’s sweat.

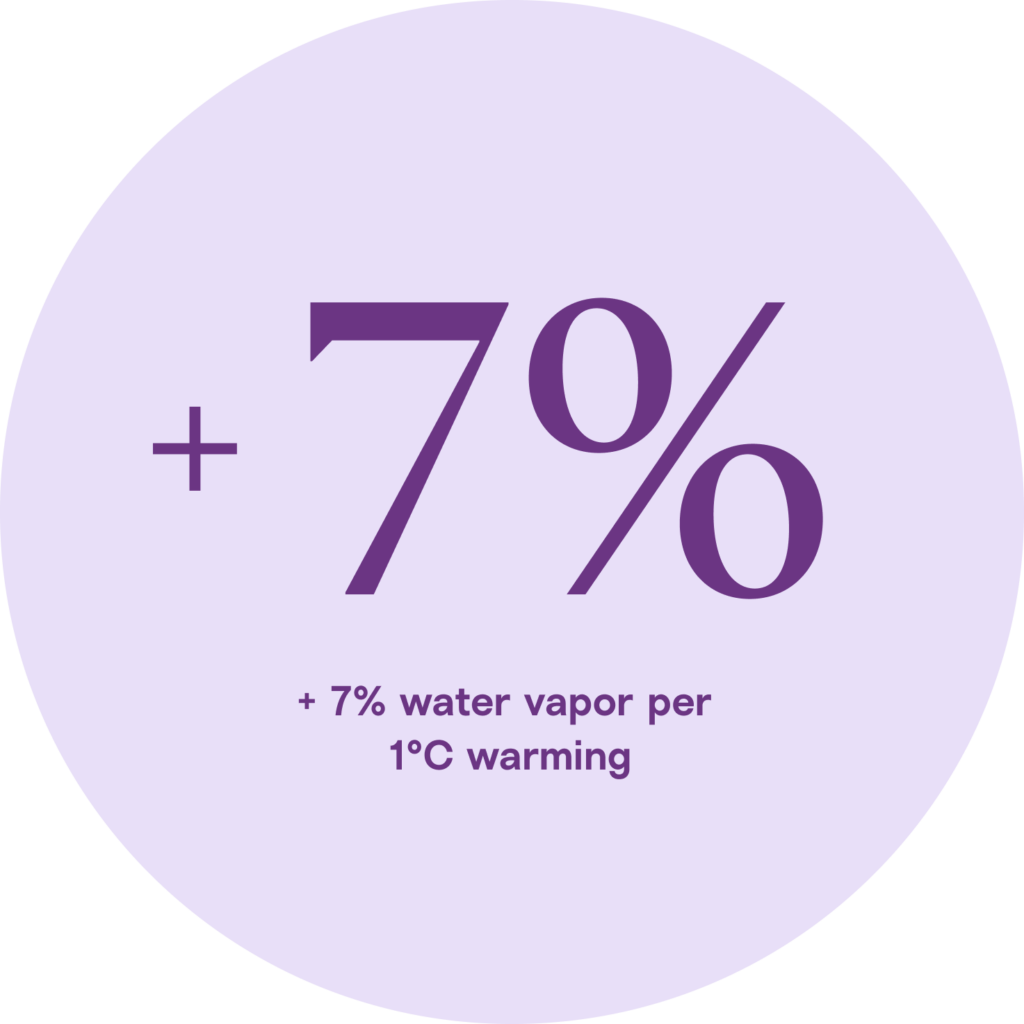

As air warms, it can hold greater and greater amounts of water vapor. The Clausius-Clapeyron equation gives us a ratio for this relationship: For every 1°C increase in air temperature, the air can hold 7% more water vapor.

This happens because at higher temperatures, the molecules in warm air are more energetic, spreading out and moving around, creating more space for water vapor.

How does warmer air impact weather?

Warmer, thirstier air impacts almost every type of weather, increasing evaporation and humidity, changing precipitation patterns, and strengthening storms. These dynamics alter weather patterns at the global and local scales.

Drought and aridification

If there is liquid water available on Earth’s surface, warm air sucks it up, lowering water levels in lakes, rivers, and other water bodies and drying out soil and vegetation. In hot deserts, the air is both hot and dry only because there is very little available water.

This increase in evaporation is pushing some areas into more frequent and severe droughts, including droughts that last longer than a year. Places experiencing prolonged drought may never recover, becoming permanently drier (also called aridification). For example, the lush Mediterranean climate of Southern Spain and Northern Africa is shrinking as areas that used to rely on wet winters aridify.

Wet-bulb temperature

Warm air becomes humid air when liquid water is available. The combined measure of heat and humidity, called wet-bulb temperature, is dangerous for the human body when it reaches high temperatures because sweating, one way our bodies cool down in hot weather, is less effective. In hot places near water, such as Chennai, India, deadly wet-bulb temperatures are becoming more common, even an annual occurrence, as the climate warms and the atmosphere holds more water vapor.

Historically, even in hot places, the nights provided some relief from the heat. However, higher wet-bulb temperatures can also cause warmer nights. Humidity acts like a blanket, trapping heat on Earth’s surface when it would otherwise escape overnight. Warm nights can have physiological effects on humans, from sleep disruption to heat-related illnesses and cardiovascular strain.

Erratic precipitation

Warmer air absorbs and holds more water vapor, it can disrupt precipitation patterns. When air can hold more water vapor, water may remain suspended for longer periods of time and be released in greater amounts. Instead of the amount and frequency of precipitation a place is accustomed to, it might experience longer periods of dry conditions or drought, followed by deluge, such as a 1-in-100-year storm or blizzard.

This combination of dry spells and heavy downpours can increase flood risk in some places. For example, during the 2024 floods in Southern Germany, many places experienced more than an average month’s worth of rain in just 24 hours, an indication of how saturated the air was. Even in places accustomed to extreme dry and wet seasons, those seasons can become unpredictable. Monsoons in South Asia have become less consistent, with longer dry spells separating wetter downpours.

Intense storms

A warmer atmosphere generally contributes to stronger storms. Over bodies of water, warm, thirsty air not only increases evaporation, pulling more water up into storm clouds, but it also warms ocean temperatures, adding energy to storms.

With hot, humid air adding both energy and moisture to storms, they can grow quickly and carry more water towards land. Already, we have seen storms intensify more rapidly than they would in a historical climate, fueled by warm air and ocean temperatures, as in the case of Hurricane Helene off the Southeast coast of the U.S.

Higher degrees of warming

As the temperature of the atmosphere increases, the dynamic between the air and moisture becomes exponentially more powerful. The Clausius-Clapeyron equation tells us that with every degree increase, the air can hold 7% more water vapor. So, air that is 10°C warmer can hold nearly 100% more water.

With each additional increment in global warming, we are likely to experience increasingly extreme weather impacts. In hotter future scenarios, such as 2.5°C, 3°C, or more of warming, there is greater uncertainty about exactly how this dynamic might affect weather, because potential increases in water vapor capacity would be so great.